All Susana Rodriguez Does is Win

(Photo: Lintao Zhang/Getty Images)

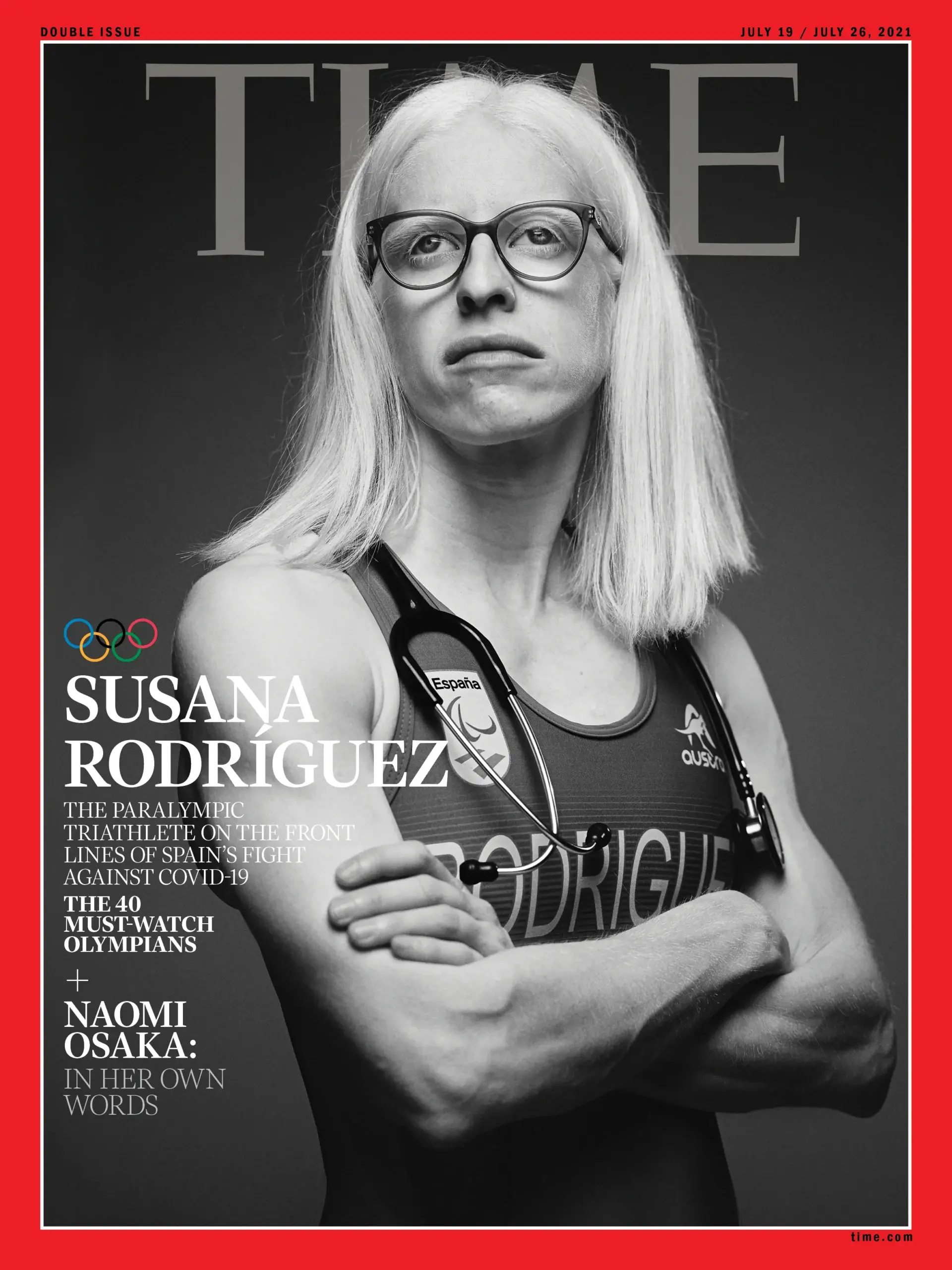

There aren’t many triathletes who have graced the cover of Time magazine, but then again, there aren’t many triathletes like Susana Rodriguez.

Born with albinism, a congenital condition characterized by the absence of pigment in the skin, hair and eyes that results in less than 5 percent vision, the 34-year-old from northern Spain merits cover star status for more reasons than one.

The sporting results speak for themselves. Alongside the likes of Netherlands’ Jetze Plat, France’s Alexis Hanquinquant and USA’s double-Paralympic champion Allysa Seely, Rodriguez is one of the powerhouses of paratriathlon. Barring one DNF in 2019 you have to go back 20 races for her last defeat; the latest victory at the end of November in Abu Dhabi securing a fifth world title.

The nature of the sprint-distance racing in the PTVI category also means Rodriguez and Sara Loehr, her guide since 2020, tackle each race as frontrunners to be hunted by competitors with less-severe visual impairment.

And then there’s the non-sporting prowess, and being on the cover of Time: arms crossed against her trisuit, stethoscope around her neck – wasn’t so much about being at the front of racing, but being on the front line in her country’s fight against COVID-19.

At a time when Rodriguez’s planned focus was winning the Paralympic title in Tokyo, the University of Santiago de Compostela medical graduate was instead part of the screening process to help protect and save lives in the worst pandemic for a century.

“I was completing my final year specializing in physical medicine and rehabilitation when lockdown started in Spain and all our medical systems became dedicated to urgent care,” she explains. “I was offered to stop working because of my disability, but I wanted to carry on because I felt l needed to serve my country in hard moments. Spain had a lot of problems with COVID-19, especially in the first wave, and my job was on a phone line where people would call in about symptoms and I decided whether to ask for a PCR test for them and their close contacts.”

The Time report covered six athletes who were working in the health system and preparing to race in Tokyo, but appearing on the cover came as a shock. “It was a very big surprise,” she explains. “I didn’t imagine it would have such a big impact. I was training in Lanzarote, at one of my last training camps before the Paralympics, and when I came back from swimming there were a lot of phone calls and messages. I was representing all the people who work in health systems worldwide and the athletes who had to face challenges heading into the Olympics and Paralympics. ”

By the time of publication, restrictions had, thankfully, eased. Even the ability to train in the Canary Islands was a positive sign following Spain’s decision to deploy some of the strictest lockdown measures in Europe, which had left Rodriguez confined to her apartment with a rowing machine, treadmill and spin bike to retain fitness.

It further underlined her resilience, and when it came to racing in 2021 in Tokyo, Rodriguez justified her status as gold medal favorite, stopping the clock in 1:07:15 with the fastest bike and run splits. Even had she not benefited from the factoring system that gives a time advantage to the more severely visually impaired triathletes, she would still have won by almost a minute.

A year on, defending the world title she also won in the Emirates’ capital last year, would be little more than a formality then? Not when you slip during race week and crack your head on the ground.

“It’s hard for me to race in the heat so I traveled to the UAE early to get used to the climate,” she explains. “We are heading into winter in Spain, and it’s raining and cold, so I went with my guide and teammate, hired an apartment and was feeling good. Then I had an accident when running which gave me a headache and backache, but thankfully racing has more power than many other things so I could still race at a decent level.

“I had a very bad swim – one of the worst swims I’ve ever had and got a lot of hits with the French athletes that hasn’t happened in 20 years of racing, and I hope doesn’t happen again. But I’m happy. It’s been 10 years of world championships with nine medals: five gold, two silver and two bronze. I could never have imagined a career in triathlon like this, and I’m incredibly happy for me and my team because without them I wouldn’t be here.”

If Rodriguez does have a chink in her armor it’s the first leg. “The most challenging thing is the swim – I don’t like it!” is her honest assessment. “I cannot communicate and don’t know what’s happening. With this genetic condition, the water is a place where I don’t feel safe, but the things that are more challenging are the things we have to train more for to improve.”

Dry land is her happy place, the track an understandable favorite, and she seemingly takes some masochistic pleasure from run-bike, run-bike, run-bike brick sessions too.

USA success in Abu Dhabi came from Paralympic medallists Hailey Danz (PTS2) and Grace Norman (PTS5), with Kendall Gretsch, who won a spectacular sprint finish with Lauren Parker in Tokyo just edged out by the Australian for gold in the wheelchair division. Melissa Stockwell also finished runner-up to Danz, but the competition for the bigger nations is becoming tougher and Rodriguez sees paratriathlon’s evolution as being positive.

The six categories for the inaugural paratriathlon at Rio in 2016 were extended to eight for Tokyo. In Paris, it will be 11, the only omission being the women’s PTS3 class, primarily because there aren’t the global numbers yet competing.

“I think paratri is growing nicely,” Rodriguez says. “The level is increasing each season and new athletes are coming into the sport. Years ago it was Great Britain, USA, Spain and France dominating everything, now we see athletes from other countries coming strong. We need more research into the classifications to make the sport as fair as possible, but it’s still a modern sport and heading in a good direction.”

Classification in parasport can be a contentious issue, as the governing bodies wrestle with the balance of the fairest possible racing, but not making the program so unwieldy it’s unmanageable or incomprehensible for fans.

RELATED: What is Paratriathlon? Understanding Triathlon in the Paralympics

In the visually impaired and wheelchair classes a factoring system known as a ‘compensation value’ is used by World Triathlon to try and negate any disadvantages due to disabilities. As such, PTVI is split into B1, B2 and B3, with the B1s, the most visually impaired such as Rodriguez, given a head start based on historic data of finish times over the sprint distance. For 2022, it was 3 minutes 48 seconds in the women’s PTVI class. Under new rules recently introduced by the World Triathlon board for next season it will be reduced to 3 minutes 11 seconds.

For context, in Abu Dhabi, Rodriguez held off Italy’s Francesca Tarantello, a B3 paratriathlete who is new to the sport and only turned 20 this year, by 32 seconds at the line. Do the math and you can see it’s not going to get any easier for Rodriguez heading into Paris, although she plans to handle the pressure differently this time. After a fifth place in Rio, the next five years became almost an obsession about one race, and the Spaniard doesn’t want a repeat. “I think it’s time to enjoy it rather than every day thinking about the same day and the same race. I had some personal challenges but the Games were the most important thing in my life for all that time. The hard work paid off but after Tokyo it was mentally challenging. If I qualify, I will do my best, but keep calm and focus on the little details, and if I arrive in Paris, I’ll push hard and try to be on the podium.”

At least in the French capital she will be able to concentrate on just one sport. In Tokyo, the track was also a focus, but the 1,500m semi-final was the day after she won paratriathlon gold.

“Racing at the stadium was like a dream, but I was very tired,” she says. “My guide said I needed to PR by more than 3 seconds, and although I qualified for the final and it was amazing to be there, I had no more left in the tank and ended in fifth place. I don’t think I’ll follow my [track and field] career further, as I want to focus on triathlon. Although maybe I’ll do some cycling before I finish.”

When Rodriguez does call time on her sporting career, she’ll happily return to her role as a doctor in Spain’s national health system as well as devoting more time to the athletics and tri club, and sports school for children with and without disabilities she has helped create. She also sees a role in helping the development of Paralympic sport in her country. “I think there are a lot of things that need to be done, and with my experience I would like to help.”

RELATED: A Sight for Fast Legs: Inside the World of Athlete Guiding