Updated for 2024: A PhD Reveals The Key Data To Winning the Paris Olympic Triathlon

What will it take to win a triathlon gold medal at the 2024 Paris Olympics? Let's take a dive into the data. (Photo: Dave Butler, George Wood/Getty)

Whether it was the Brownlee brothers in a two-up breakaway on the bike, Gwen Jorgensen running through the field again during her record-breaking win streak or Flora Duffy heading out on another lone solo pursuit, since 2009 we’ve not only seen epic racing in the top level World Triathlon Series, but we’ve seen races won in very different ways.

But what does it take to win over the Olympic distance at the elite level today, and where should the world’s best triathletes be putting their training focus to have a chance of triathlon glory at Paris 2024?

Dave Butler, who has a PhD in computer science from the Alan Turing Institute in London, recently took on a project to help understand the evolution of standard distance racing – a 1,500-meter swim, 40-kilometer bike and 10-kilometer run. As well as his own interest in data science, Butler had another compelling reason to undertake the research: He is the partner of current world champion triathlete Beth Potter, who will represent Great Britain at the 2024 Paris Olympic Games.

“We are always looking for ways to understand what is required to win a race and how an advantage can be gained. Simply watching races, even very closely, can often lead to very biased and incorrect conclusions about what is actually required to win,” Butler says, of a style of pro triathlon that often gets overlooked when it comes to data analysis—due to the complexity of race dynamics in draft-legal racing. “Taking a step back and looking at the trends in data over a period of time provides a more objective way to understand the current demands of the sport. The analysis we are discussing here is the baseline we use to inform more advanced models of races and requirements.”

Butler dug in deep on hundreds of individual results and their relationship to each other in a given event. From this he highlights three of the key requirements across swim, bike, and run for both men’s and women’s racing – these quantify what fans and announcers see, and what athletes feel out on the course.

First, we break down his methodology:

Digging into the Olympic-level triathlon data

To analyze the data, Butler focused on the World Triathlon Championship Series. As the leading short-course series in the world, the WTCS runs on an annual basis with a different number of events each year – often five to eight – leading up to a grand finale at the end of the season. Run by the international governing body, World Triathlon, athletes earn points through the racing that helps earn Olympic selection. In short, the WTCS is where all the best triathletes in the world race one another.

Butler analyzed all 79 standard distance races that have taken place since the series began in 2009 (prior to 2009, top-tier draft-legal events were known as “World Cups”). For the purposes of this research, the 31 sprint distance events and other altered formats, such as super-sprint eliminators or races with shortened swims, were discarded.

To help group the data, the periods were split into four-year Olympiads (the time between London 2012 and Rio 2016, for example), with the exception of 2020, where the break from racing due to the pandemic was used as a preferable cut-off rather than the following year’s Games in Tokyo.

He then looked at each discipline in turn, using different metrics to understand how the athletes who had finished on the podium performed.

For the swim and the run, he analyzed:

| Swim and Run Metrics Analyzed | |

| Required position | Where the athlete ranked in the field for their split |

| Required time | How much time the athlete in question gave up to the fastest split |

| Raw Time | The athlete’s split time in the discipline, although little importance was put on this due to variances in course measurement |

For the bike, Butler only looked at “required time,” with required position, due to bunch riding into T2, and raw time, because of the variation in courses and pack dynamics, rendered virtually meaningless.

It’s also worth noting that each discipline doesn’t exist in a vacuum. “The idea behind the metrics here is to gain an understanding of the relative importance of each discipline. They are useful to understand the trends in previous years and extrapolate as to what might be required in subsequent years.” Butler says. “Here we analyze the swim, bike, and run requirements separately, but in a race, of course, the three disciplines are heavily related. I do run more complicated models, which look at the demands for the bike based on swim scenarios, and the run, based on the first two disciplines, but at present to preserve any competitive advantage it may give Beth, we’re not releasing these publicly.”

Butler looked at the podium finishers plus the fifth-placed athlete to help understand how athletes needed to perform in each discipline to achieve overall success.

To prevent the article becoming unwieldy, we will look more deeply at the women’s racing but still provide the key takeaways for both the women and men.

What does it take to be successful in the women’s triathlon swim?

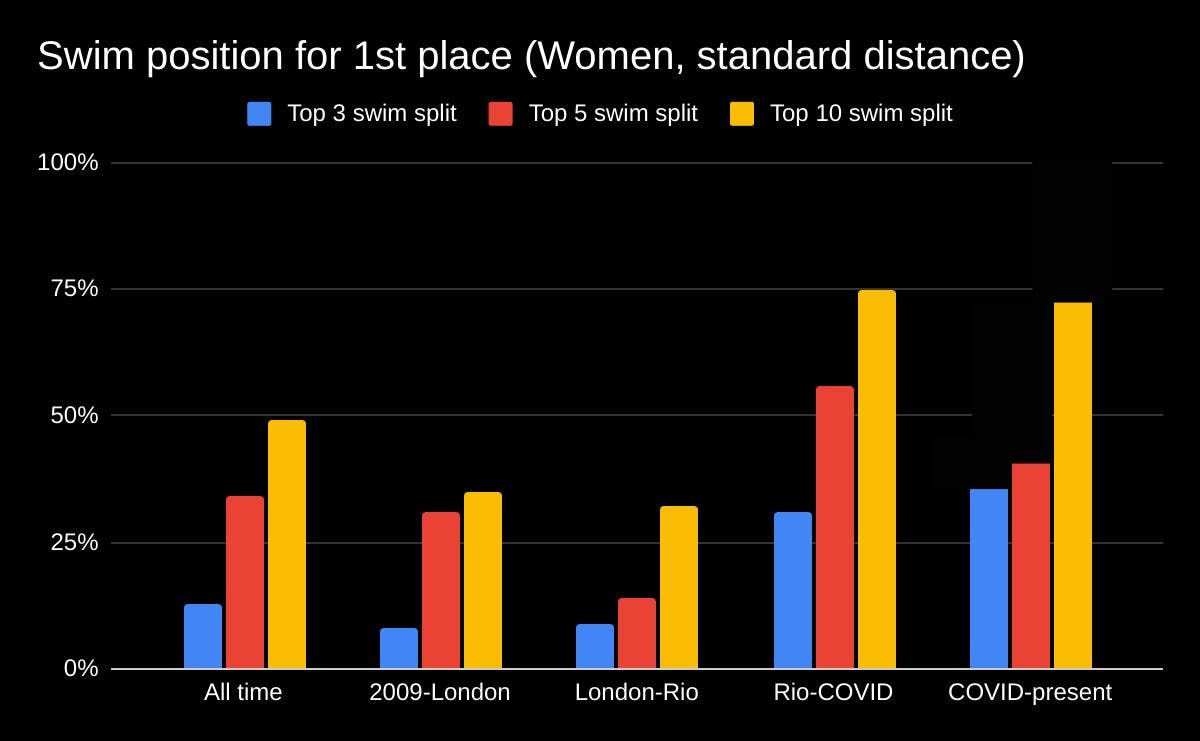

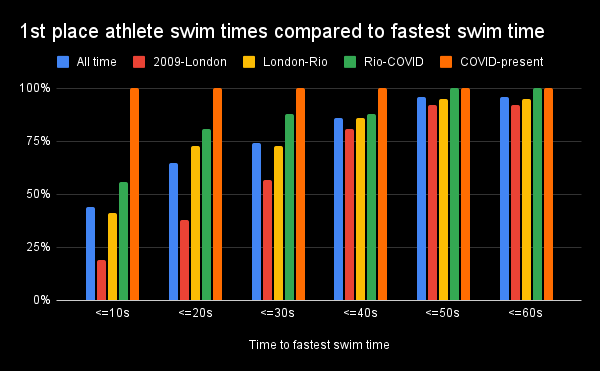

In the graph, below, you can see how since London 2012 the winning female has increasingly been towards the front of the field coming out of the water. The data shows the same for the other two podium places, but interestingly to finish fifth it’s less important to be a front-pack swimmer. In fact, recently it’s become even less important.

This situation is underlined when we look at the graph, below, that shows the time difference between the swim leader and race winner. From the pandemic until last year’s Paris test event, every winner in a standard distance WTCS race was within 10 secs of the lead coming into T1. Potter’s wins in Paris (35 sec gap) and last year’s WTCS final in Pontevedra (16 sec), and France’s Leonie Periault victory in Yokohama (18 sec) in May, has seen the winner come slightly further back in three of the past four races.

“The data shows that the swim is more important now than it ever has been,” Butler concludes. “People who have taken a keen interest in WTCS racing in recent times won’t be surprised by this.”

We could argue it reflects the changing face of women’s racing, where the strongest swimmers, like the Bermudian Olympic champion Flora Duffy take charge of the race from gun to tape. Conversely, with Duffy injured and absent from the test event and trying to build back into form in time for the Olympics, there’s a case to be made that if an event is missing its key swim-bike protagonists, proximity to the front in T1 is less critical.

What does it take to be successful on the women’s bike in triathlon?

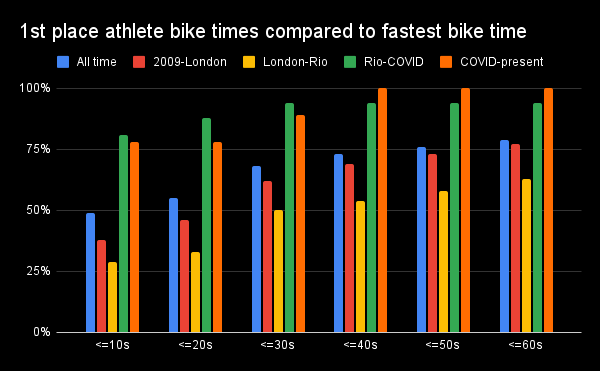

Butler only uses one metric to analyze bike performance and that’s the athlete’s time behind the fastest bike leg.

The graph, below, shows how close the race winner has been to the fastest bike split for each period. We can see that since the Rio Olympics there is a step change in the number of times the winner has a bike split within 10-60 sec of the fastest bike time.

“In the 2009-London and London-Rio cycles, only 38% and 29% of the time did the winner have a bike split within 10 seconds of the fastest bike split,” Butler says. “However, the two most recent cycles corroborate the trend of the breakaway succeeding that many will have observed. In short, once you are in the break, stay there!”

What does it take to be successful on the women’s run in triathlon?

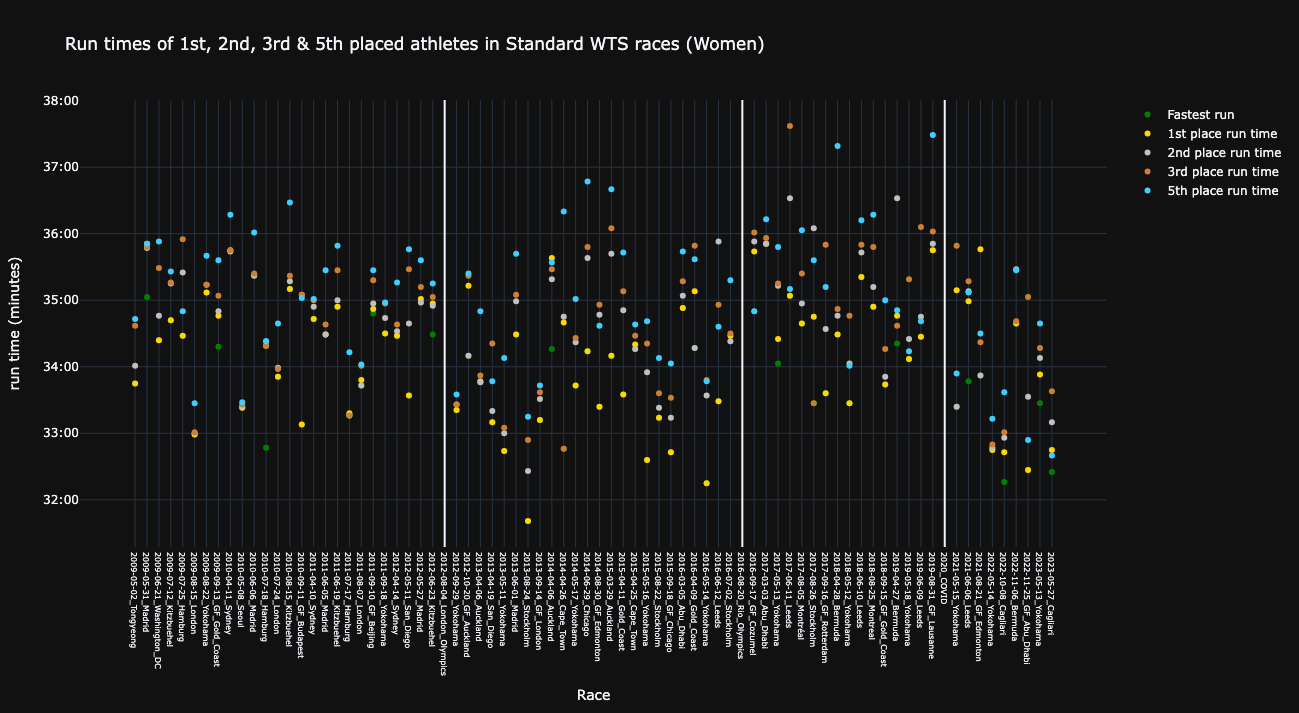

As with the swim, Butler looked at required position (where the athlete ranked in the field for their run split), required time (how much time the athlete lost to the fastest runner), and raw time.

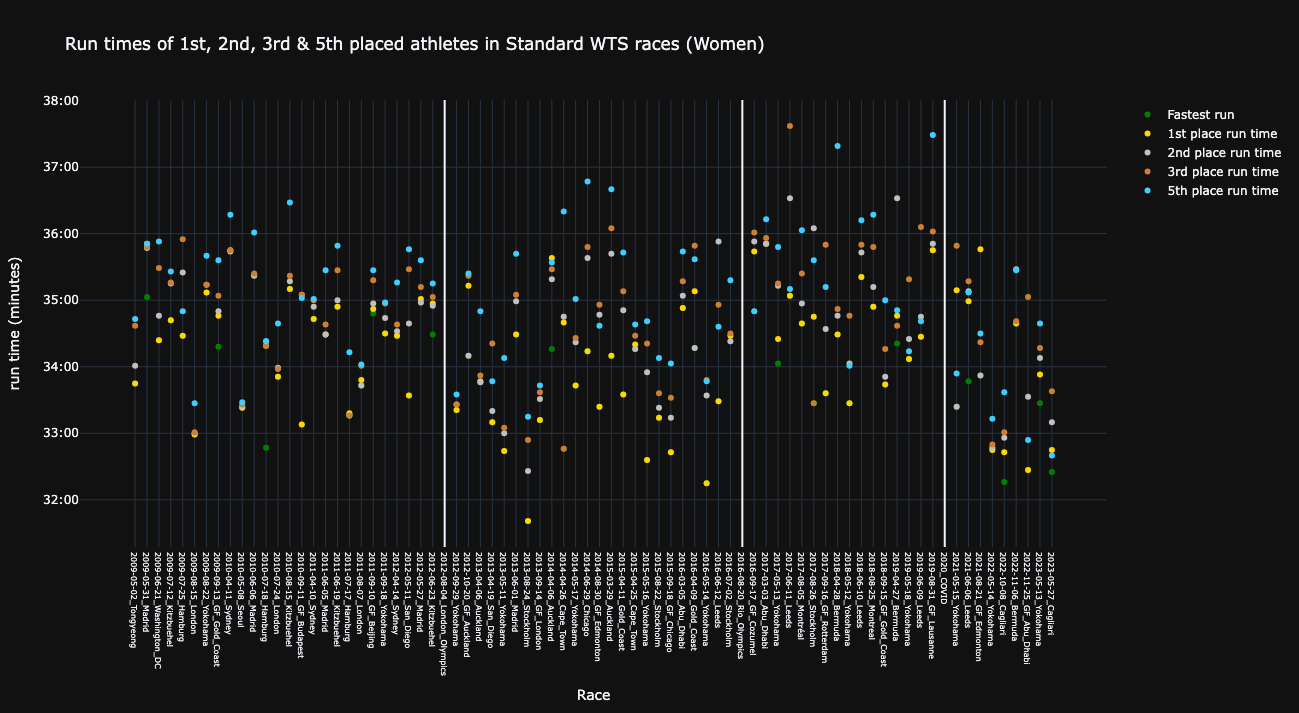

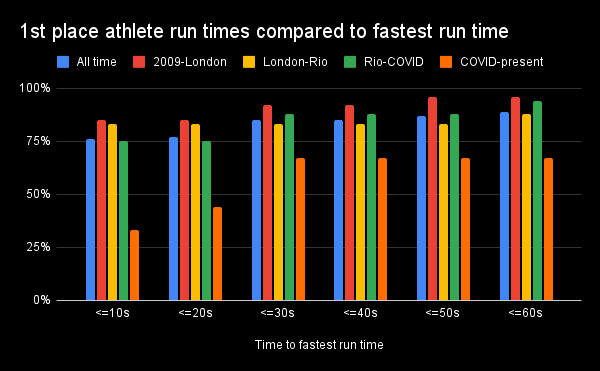

As the graph, below, shows, in the post-Covid era, the winner has been the fastest runner, top-three, or even top-five runner far fewer times in WTCS racing. Whereas up until the pandemic, the winner had the quickest split in over 50% of races, this has now dropped to only 38%.

The graph below shows how much slower the race winner is than the fastest runner, suggesting that since the return to racing post-pandemic, not only are the bike breakaways sticking, but they are gaining enough of an advantage that the chasing pack are out of contention by the time they reach T2.

Due to the difference in course lengths and terrains, the raw 10km times don’t have much statistical significance. It doesn’t mean they aren’t of interest though. For example, the four years from London to Rio produced some of the fastest WTCS runs on record. There is also a marked difference in how run splits have improved from the pre- to post-pandemic cycle.

“The data shows there has been a clear evolution of women’s racing since 2009. Where a strong run leg could once mask a weakness on the swim or the bike, in 2024, that is rarely the case,” Butler says. “Today’s female short-course triathletes have to be front-pack swimmers and prepared to work in the breakaway to make the advantage stick. If they do that, then although they still need to be competent runners, they don’t always have to deliver race-best 10km splits to take the tape – although they still often produce top-three run splits to win!”

What about the men?

Men’s WTCS racing shows a different picture of the changing demands to reach the podium. While the importance of being at the front of the swim and part of an early bike breakaway has lessened, you can’t be cut adrift in the water – missing the main pack means your chances are all but over.

Equally you can’t drop time on the bike, although pack dynamics can often lead to bike splits being similar and breakaways have become much more rare in recent years. The final takeaway is perhaps the most important: If you can’t run like the wind, you can rule out the podium.

The takeaways

To be successful in the post-pandemic era, female draft-legal triathletes at the Olympic distance typically need to:

- Exit the water within 10 seconds of the swim leader – and typically within the top 10.

- Ride within 10-20 seconds of the fastest cyclist (in years past, slower riders could still run up to the podium).

- Fully commit on the bike leg, even if it means sacrificing run speed

On the men’s side however, we see some different trends.

- You don’t need to produce a top 10 swim split to win, but you also can’t lose much time in the water. Generally, the winner needs to reach T1 within 30 seconds of the swim leader.

- You cannot lose time on the bike. Since the start of the World Triathlon Series in 2009, triathletes who end up on the podium are increasingly producing bike splits on par with the fastest cyclists in the race.

- The demands for the 10km run leg haven’t changed too much. You still have to be fast. Around 50% of the time the quickest runner wins the race and it is rare to win if you can’t deliver a top five run split. Though there are often questions around run course accuracy, a run in the sub 30:30 range is typically needed to win.