Feature: Looking Back at 40 Years of Professional Triathlon

(Photo: Mike Plant)

Table of Contents

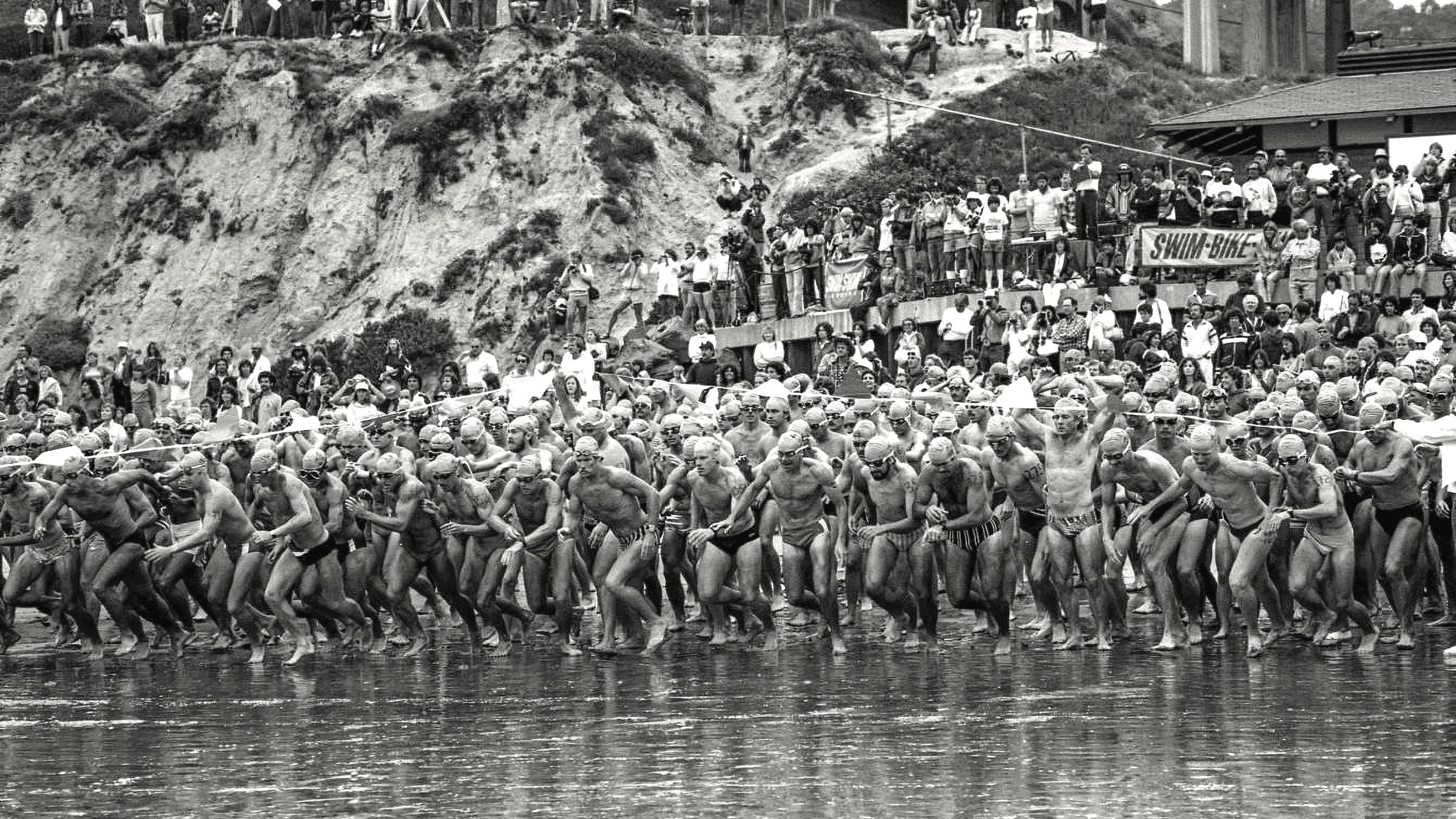

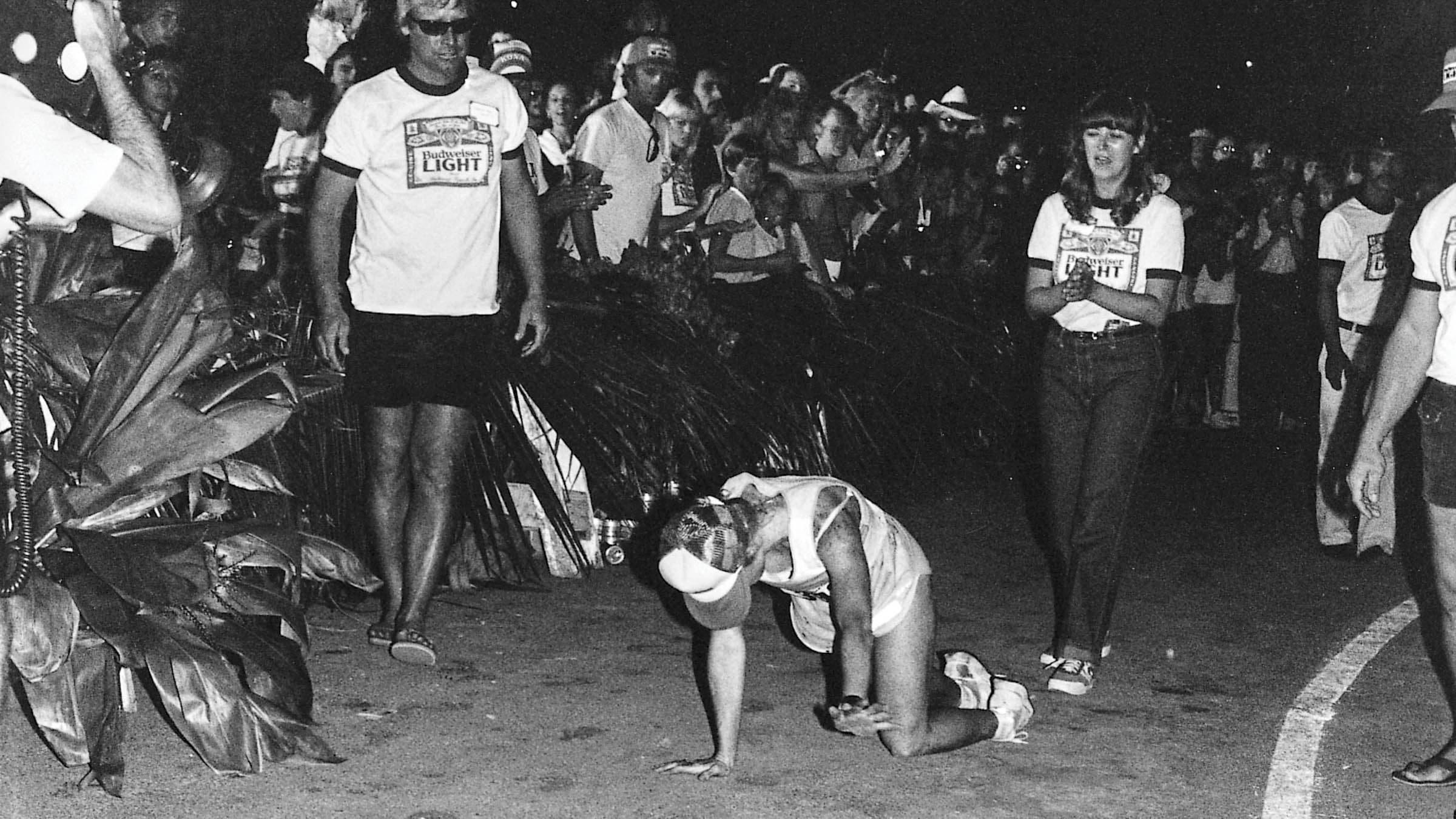

While modern triathlon was born in 1974 on the sands of Mission Bay, San Diego, and Ironman was created in 1978 in Hawai’i, it was 1982 when the true spark was lit. Julie Moss’s famous crawl to the finish line at Ironman Hawaii in February was beamed to living rooms across the planet via ABC’s Wide World of Sports, and the sport was primed for a boom. Up until that year, the term “professional triathlete” didn’t exist, as no race had offered prize money. But starting in 1982, professional triathlon—and the sport as a whole— would never be the same.

1982-1986: The Dawn

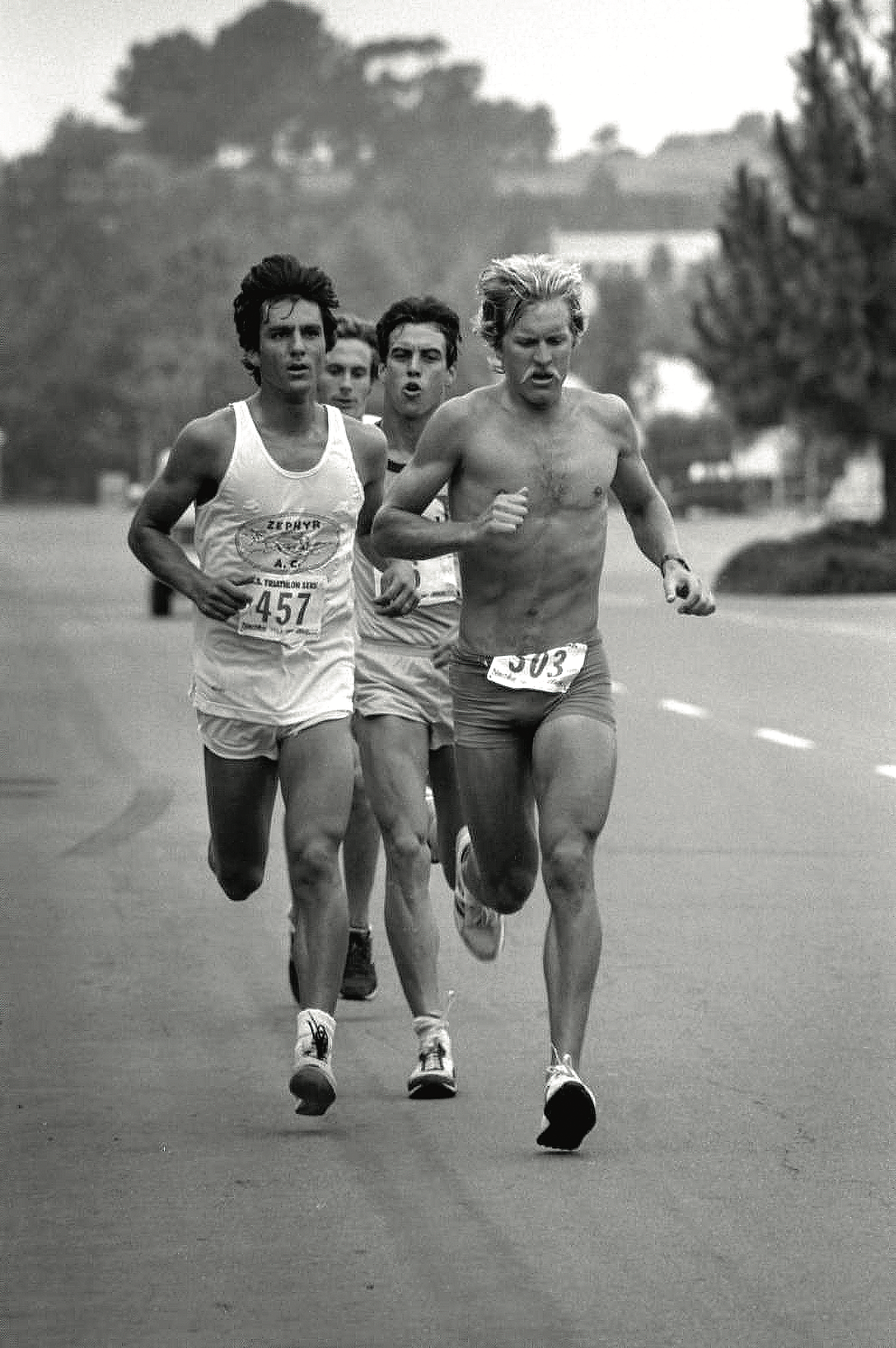

The late, great triathlon journalist Mike Plant opined that it might have been the most influential triathlon in the sport’s history. The venue was Torrey Pines State Beach in San Diego, California, the date was June 12, 1982, and it was the first race in the new U.S. Triathlon Series, the brainchild of innovators James Curl and Carl Thomas, that would run for the next 11 years.

It was also the first meeting of what would become the Big Four – Dave Scott who won by two minutes, a 22-year-old Scott Molina, who’d just barely scraped enough gas money together to get there, the entrepreneurial Scott Tinley, and, in his first triathlon, a fresh-faced lifeguard named Mark Allen.

There was equal prize money of $800 for the men’s and women’s field. Julie Moss and Kathleen McCartney lined up for a repeat of their February 1982 race in Hawaii—the one that featured Moss’s famous “crawl” to the finish line—and were joined by the third-place finisher from that day, Sally Edwards, who went on to write several books on the sport, including the seminal Triathlon: A Triple Fitness Sport.

RELATED: A Brief History of Women in Triathlon

In hindsight, it was a who’s who of triathlon for the years to come. And yes, legendary triathlon historian Bob Babbitt was there, too.

But it wasn’t just about who was at the pointy end. The USTS would go on to deliver over 120 events in 30 different US cities during its lifespan, and while it paid out more than $1,000,000 in prize money, it also attracted over 100,000 athletes until its end in 1993.

From the get-go, Thomas—a former advertising exec with Speedo— envisaged the pro field as a marketing investment alongside the bright lights of TV and newspaper exposure, cool branding, sponsorship deals with the likes of Bud Light and Coca-Cola, and taking it direct to the hearts of cities, closing down downtown areas in Chicago and Miami. Curl and Thomas literally wrote the race manual for future events too, including ground-breaking initiatives such as bike racking and wave starts. They were even responsible for pulling back the distances from an initial 2km swim, 35km ride, and 15km run to the now-familiar Olympic- or standard-distance 1.5km swim, 40km bike ride, and 10km run—designed to attract sign-ups. Not only were those distances single-sport participants were already familiar with, chiefly—and unlike the Ironman (there was only one at this point)—mere mortals could consider them achievable.

Handwritten results from the 1982 Torrey Pines Race. (Photo Credit: Mike Plant)

With the draw of prize money and no appearance fees—a battle Thomas fought to the end—the Big Four were rolled out whenever possible. As Molina recalls. “We did attract a lot of attention, underlining these races weren’t fun runs, but high-profile TV events. I probably did three-to-four newspaper interviews and a TV interview prior to every race. In Chicago, I’d be on the 6 p.m. news the night before, and if I won there’d be a full page on the back of the Chicago Tribune with a picture of me crossing the line. We had tremendous coverage early on.”

“We did attract a lot of attention, underlining these races weren’t fun runs, but high-profile TV events.”

The fledgling USTS was the first, but it wasn’t the only offer of prize money for the pros in 1982. In November, California-based race promoter Hans Albrecht put $17,000 on the line for his “U.S. Pro Championships” in Malibu—a race title to match the 10-fold increase in dollars for anything seen before. It was held just three weeks after Ironman Hawaii (the second of that year, as 1982 would see two events), where prize money wouldn’t be on the line for another four years.

It was also an example of where the pros didn’t have to be taking the tape to wield influence on the rest of the sport. Plant’s recollection in his Trihistory.com story on the Malibu event includes Allen having to be rescued from a “frigid Pacific Ocean swim.” As an advert for tri-specific wetsuits, it was the best you could want. The other sweeping benefit to the sport that organizers couldn’t have known early on was how omnipresent the Big Four would be for the decades that followed. Kona offers perhaps the best example: From Tinley in February ‘82 through to Allen in October ‘93, one of the big four claimed every Hawaii title offered.

“It didn’t hurt that the Big Four were the Big Four,” Barry Siff, former president of USAT remembered. “You saw the same guys. You weren’t seeing names from Europe that you don’t recognize.”

Yet for Molina it was 12-15 years of a “zombie haze” of training and racing. “In general, we thought more was better,” he said. “I caught around 60 flights a year for more than a decade. There was a lot of traveling, and a lot of racing, and it went by in a blur.”

Moss’s crawl in 1982—or more precisely its capture by the ABC TV cameras for its Wide World Of Sports broadcast—had also given Ironman a welcome second spike of interest after Barry McDermott’s 10-page Sports Illustrated article covered the initial Hawaii Ironman in 1979. Entrants for 1983 hit four digits.

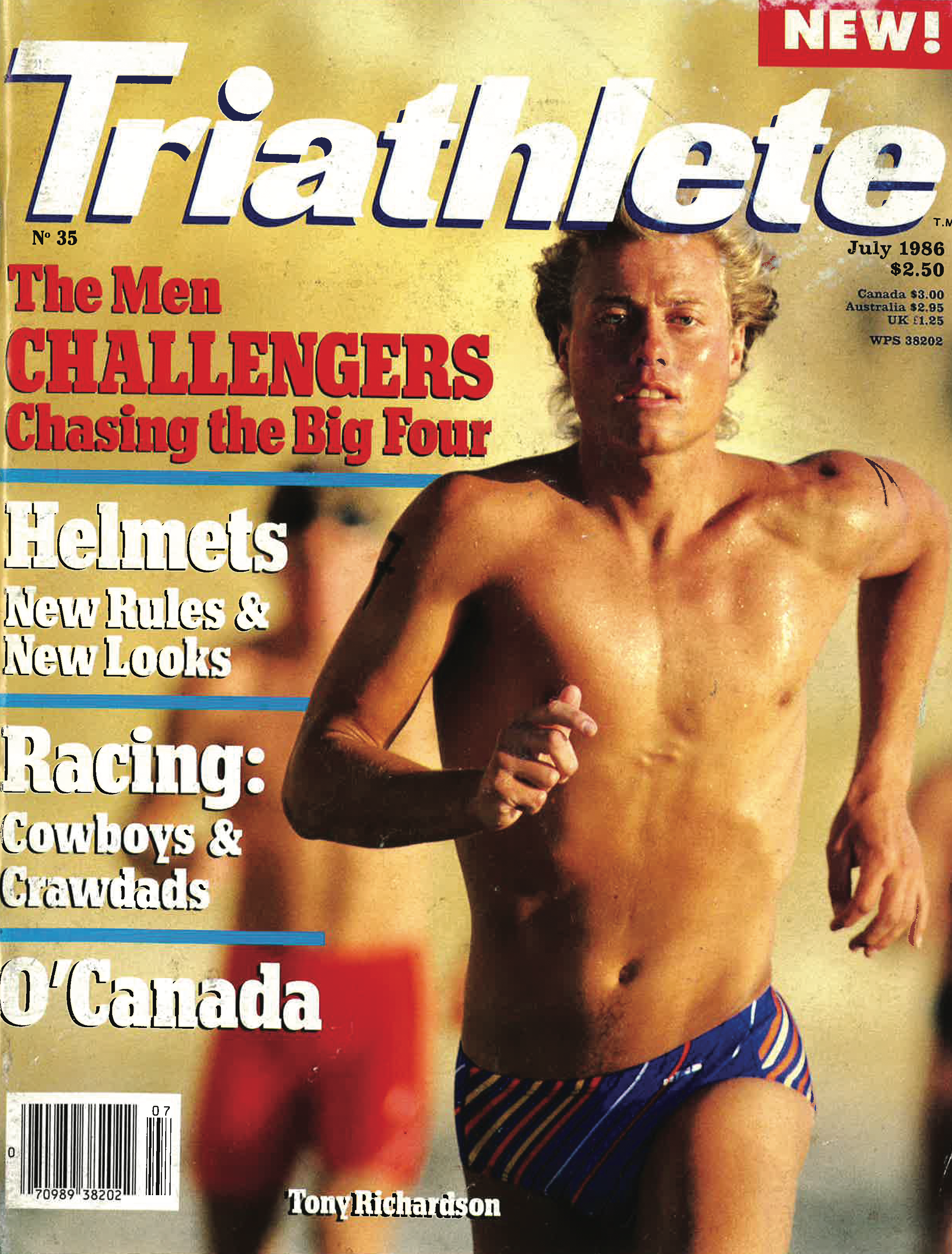

It wasn’t just the racing though. As seen with Allen’s hypothermic swim in Malibu, anyone wanting to try triathlon needed guidance, and brands finding their feet in this new world needed a peg of integrity for products. As magazines such as Triathlon and Tri-Athlete merged in 1987 to become Triathlete, these tanned, honed professionals were the obvious crash test dummies.

“It was a burgeoning sport, and manufacturers needed a way to market their new products, whether it be watches, bicycles, wetsuits, sunglasses,” Molina explained. “This was before the days of Oakley, Quintana Roo, and everything we know of the industry now. It was years before aerobars were invented. The magazines were the conduit, and that’s how they got the word out.”

Not every product always hit the mark. “There were ridiculous ones and ones that went on to change the industry,” Molina added. “I was sponsored by a wetsuit company but those first swimming wetsuits—before Yamamoto rubber—were made from the same material as surfing wetsuits. They rubbed you to death, and I still have scars.”

Aerodynamics, previously the domain of track cycling, caught the imagination even more. “Our sport took it on hook, line, and sinker. We had disc wheels, cow-horn bars, 650c wheels on the front to get you lower, down-sloping tubes on steel bikes. The cycling industry started to take note and the age-groupers grabbed on to the fact that they needed a different bike for triathlon.”

As well as the equipment, a hot topic was how to actually train. “There were no coaches,” Molina added. “So, people looked to us for weekly and monthly training programs. We wrote articles, Tinley had a magazine column, and we’d answer questions in interviews about the type of training we thought was necessary.

“It was similar to the running boom in the ‘70s, when everyone looked to Frank Shorter and Bill Rodgers to see what those guys were doing. Reflecting back, people took on totally unrealistic training regimes. They had a full life and, all of a sudden, would put this 25-hour/week training program in too. Although we were too busy doing our own thing to take too much notice.”

1986-2000: The Cresting Wave

It was time for Ironman to up the ante. In 1986, having been settled on the Big Island for the past five years, the event offered its first prize purse of $100,000. As well as Dave Scott winning his fourth title, it also attracted Paula Newby-Fraser for the first of her record eight wins and title of undisputed Queen of Kona.

Barry Siff had been living in Omaha, Nebraska, when he found triathlon through a master’s swim program in the same year. When he made the trip to Hawaii to support friends who were competing, Scott wasn’t really on his radar, but it wasn’t long before he had Scott’s first triathlon training book, signed with the inscription: “To Barry, perhaps one day I’ll see you at the start line.” Siff would make his own racing pilgrimage to Kona four times.

“Dave wrote the triathlon bible before Joe Friel wrote The Triathlon Bible,” said Siff, of the now-famous training tome. But it wasn’t just books. “The media around triathlon was pretty significant,” Siff said. “It was this amazing, cool sport, and the TV show of Ironman was a big, big, deal. Today, I’m not sure if it’s as big. But it wasn’t just Ironman. There was a 30-minute show on ESPN called Running & Racing where the great runner, Marty Liquori, was the announcer. It would have five minutes on stretching and getting in shape, then feature a race each week—invariably something on triathlon. When I was president of USAT we tried to replicate it, but couldn’t sell it.”

If professional racing was bringing amateurs to the sport, it was given a further leg up in 1989 with the historic Iron War—forever triathlon’s most famous race. Dave Scott versus Mark Allen, The Man versus The Grip, duking it out in record times. It was a gift to the sport, and has been capturing the imagination of wannabe triathletes for the past 43 years.

Yet it was also the year that Valerie Silk sold the Ironman brand to the World Triathlon Corporation, setting it on a new path that didn’t necessarily align with the hopes of all pros. It was developing towards—as Scott Molina puts it—“a more age-group centric organization.”

It wasn’t just about swim, bike, and run. If duathlon today feels like a long lost relative to triathlon, in 1989 it was more like a chippy younger brother—a large part of which can be laid at the feet of Zofingen, a Swiss city that helped spawn Powerman duathlon. A long-course run-bike-run event—originally called a biathlon—it started in June 1989 and remains a beast of an endurance test. The initial distance of 2.5km run/120km bike/30.5km run would eventually settle on an attritional 10K run/150K bike/30K run.

Zofingen will host this year’s long distance world duathlon championship, but no longer has the cachet of its early days when it acted as duathlon’s answer to Hawaii. Its list of winners included many of the names made famous on the Big Island: Allen, Molina, Newby-Fraser, and perhaps most famously—for the locals at least—Natascha Badmann, Zofingen champion in ‘96, ‘97, and 2000. The Swiss Miss also made history by becoming the first European woman to win the Ironman World Championship—a title she would go on to capture six times throughout her career.

To illustrate its status, in 1993, the prize money in Zofingen reached $200,000—more than Ironman Hawaii. But while duathlon’s popularity has ebbed and flowed, the sport suffered greatly from triathlon’s approval for Olympic status in 1994. If you couldn’t swim well enough, there was a good chance you’d be left behind.

Even the origin story of the Olympic movement that would go on to further change the sport of triathlon goes back to 1989, with the founding of the International Triathlon Union and its first World Championship, held in Avignon in France. It was won by Allen and New Zealand’s Erin Baker.

As the decade progressed, the sport was spreading worldwide. “Europe in particular had races everywhere,” Molina recalled, having registered over 100 professional wins across the globe. “Ironman was just starting to branch out internationally. I was lucky. Having success early meant I got a lot of invitations to travel to races in Australia, Sweden, and France. Although wonderful, those were not easy trips. To travel internationally, do an Ironman and head back, and expect to be on your game again the next week. It was an interesting time, I never thought there would be hundreds of thousands of people wanting to take on an Ironman.“

But once the initial glamor and newness of the sport wore off, it seemed like mainstream coverage also dwindled,” Molina added. “It seems to have morphed into mostly age-group sport worldwide—Ironman is certainly. The pros got off to a good start in the ‘80s, but as a group we lost our way a little bit in the ‘90s. I don’t blame the Olympics for that—it brought so much attention to the sport—but somehow, our pros as a group didn’t organize themselves well enough.”

RELATED: Current and Past Pros Share Their Favorite Women’s Triathlon History Moment

“The pros got off to a good start in the ‘80s, but as a group we lost our way a little bit in the ‘90s…somehow, our pros as a group didn’t organize themselves well enough.”

2000-2013: Big Growth, Big (Big) Money

This century started with a massive milestone for the sport: triathlon’s appearance in the Olympics. The sport then rode its Olympic coattails throughout the early 2000s—prize purses grew, race series expanded, and thousands of new triathletes found their way into the once-obscure sport.

Although the spotlight was on short-course racing at the beginning of the decade, there was quite a bit bubbling up on the Ironman front, too. In the few years surrounding 2000, the World Triathlon Corporation (WTC) introduced some of its now-classic North American Ironman courses—Lake Placid, Arizona, Coeur d’Alene, and Wisconsin—and continued its global expansion (South Africa, Asia, Korea, and Malaysia were all introduced in 2000).

“You kind of knew something was catching fire when you’d go to places like Madison and Tempe, where races would fill right away,” said Ironman corporate operating officer Shane Facteau. “In a similar fashion with Nice and Austria, you saw that footprint continue to expand, which created more athletes, which created more buzz, which created more word of mouth, which was sort of the beast feeding itself. When all these events came in during that iconic era of 2000 to 2006 is really what cemented Ironman and led it to where it is today.”

The WTC had offered some half-distance options in the past, but it officially announced the Ironman 70.3 series in 2005, creating a more approachable entry point into the long-course world. In 2006, the first Ironman 70.3 World Championship was won by Samantha McGlone and Craig Alexander in pancake-flat Clearwater, Florida, where the race took place before moving to Henderson, Nevada in 2010 and later rotating around the world.

Meanwhile, big things were happening on the pro non-drafting short-course circuit. In 2002, the Life Time Triathlon Series began with the Minneapolis event offering $50,000 to the winner. By 2003, the prize purse increased to $500,000, offering $50,000 for both the male and female winner, as well as a $200,000 winner-take-all prize for the gender-equalizer category. In 2007, Life Time expanded the series to New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Dallas and added a bonus incentive for any athlete who could win all five. That year, Greg Bennett did—and took home more than $500,000 thanks to the bonuses and series payouts.

RELATED: The Year The Bennetts Ruled The World

“It was a year where it all came together and that was what was really special,” Bennett said. “What I realized in my career is that whoever adapts the fastest is who will win. When non-drafting started to be where the money was going to be, I adapted probably faster than others through a lot of conscious planning. I think triathlon keeps improving—there are rollercoasters and ups and downs, but there’s always different kinds of opportunities.”

“I think triathlon keeps improving—there are rollercoasters and ups and downs, but there’s always different kinds of opportunities.”

The year 2007 was also noteworthy because of another short-course race: the Hy-Vee ITU World Cup in Des Moines, Iowa. Hy-Vee, a regional grocery store chain in Iowa, got on board to offer a $700,000 prize purse—the largest in the sport’s history at the time. American Laura Bennett and Austrian Rasmus Henning each scooped up $200,000 (and a new Hummer H3) for winning the inaugural race. (For reference, at the time, Ironman World Championship winners each earned $120,000.) The race also later served as the final U.S. Olympic qualifier for the Beijing Olympics (2008) and the World Triathlon Corporation’s 5150 Series U.S. Championship (2011).

In the popular imagination, 2007 marked a new Ironman legend when a seemingly unknown competitor took Kona by storm in her first year of going pro. Great Britain’s Chrissie Wellington raced her way to the first (of four) Ironman World Championship titles, breaking the women’s marathon record in the process with a 2:59:58.

“Chrissie’s victory in 2007 marked a true changing of the guard,” said triathlon legend Mark Allen. “Even her acceptance speech was unique and different from what we had been hearing for many years—it had an honest openness that was a refreshing blend of brashness and innocence. It mirrored her racing, which was also brash yet innocent in the sense that she just went for it and blew away what had been the gold standard of times and how to win.”

RELATED: Recalled: Chrissie Wellington’s Sparkling Kona Debut

The age-group scene also grew as USA Triathlon surpassed 100,000 members, and triathlon entered into the mainstream with Hunter Kemper becoming the first elite triathlete to appear on a Wheaties box. Kemper went on to be the top American male at the Beijing Olympic Games, placing seventh. Germany’s Jan Frodeno and his now-wife, Australian Emma Snowsill, both won gold.

On the heels of the Beijing Games, the ITU launched the seven-race Dextro Energy Triathlon ITU World Championship Series in 2009, with a year-end world championship to determine an overall winner. (It was later renamed the ITU World Triathlon Series in 2012 and then renamed World Triathlon Championship Series in 2021.) The prize purses got bigger—$150,000 at each of the events and $250,000 at the Grand Final— the TV coverage expanded and massive crowds gathered to watch the fast-paced races held in iconic cities such as Madrid, Washington D.C., and Hamburg.

In the midst of this boom, a new long- course race series brought hope to both pros as an additional source of income and to age-groupers looking for an alternative long-course experience. The Rev3 Triathlon Series kicked off with a half-iron distance—Rev3 Quassy, held at an amusement park in Middlebury, Connecticut. The initial Quassy event ($100,000 prize purse) grew its prize purse by $50,000 in 2010 and expanded into a three-race series with

Rev3 Knoxville and Rev3 Cedar Point; athletes could earn a $125,000 bonus for winning all three events. By 2012, Rev3 had 10 events on its calendar and pros such as Richie Cunningham, Cameron Dye, Mirinda Carfrae, and Nicole Kelleher made frequent appearances.

“For a good three or four years, the Rev3 Quassy race was the highlight of my mid-year racing,” said three-time Ironman world champion Mirinda Carfrae. “It always attracted a very strong field with its big prize purse. That, plus a tough course, made for super-competitive racing.”

Heading into the London 2012 Summer Olympics, the sport kept growing and USAT membership rose to more than 500,000 combined one-day and annual memberships—a record at the time. Alistair Brownlee won gold in London, sharing the podium with Javier Gomez (silver), and his brother, Jonathan Brownlee (bronze). In a thrilling photo finish, Nicola Spirig (gold) edged out Lisa Norden (silver) in a final sprint, with Erin Densham (bronze) two seconds behind.

Also in 2012, the WTC pulled off the first—and only—iteration of Ironman New York City, a U.S. Championship event that served up a lot of drama between a sewage spill scare, a tragic death during the swim, and an unprecedented entry fee: $900. The difficulty of hosting an event in such a large city led to its cessation.

RELATED: Recalled: The One-and-Done Ironman in New York City

2013-2022: Darkness Before the (Second) Dawn

Triathlon hit a peak around 2013 in terms of growth, particularly with prize money and age-group participation; 2014 brought a shift. The Life Time Tri Series cut most of its pro prize purse to focus on enhancing the age-group experience. Hy-Vee discontinued its high-dollar race after the 2014 edition, citing concerns about long-term viability. Rev3 ended its pro prizes and instead tried out an amateur program. Even Ironman made the decision to cut the prize money and Kona slots at nine of its events in order to pay larger sums at select races.

On a more optimistic note, in 2014 the NCAA approved triathlon as an Emerging Sport for Women. USAT contributed $2.6 million to assist collegiate programs and offered its first high school national championship in 2016. (They’re currently on track to become an official NCAA championship-level program by 2024.) Ironman also launched the Women For Tri initiative with Life Time Fitness, offering grant funding to triathlon clubs to support female participation initiatives.

After a few years in Nevada, Ironman started rotating venues for the 70.3 World Championship, traveling to Canada (2014), Austria (2015), Australia (2016) and back to the U.S. (2017)—and continuing to make its way around the globe. As a sign of the international growth of Ironman during this era, the field at the 2016 Ironman World Championship boasted the largest and most diverse group of athletes in history at that point, with two-thirds of the 2,300 participants coming from outside the U.S.

On the ITU circuit, USAT Collegiate Recruitment Program athlete Gwen Jorgensen began her domination around 2014 with a record-breaking season as the only woman in WTS history to win eight career series events. After a perfect streak in 2015, Jorgensen went on to win gold at the 2016 Rio Summer Olympic Games—becoming the first and only American man or woman to do so.

Triathlon also made its debut at the 2016 Paralympic Games, where 60 athletes competed across two genders and 6 paratriathlon classifications. On this global stage, a new crop of triathlon icons emerged, including gold medalists Allysa Seely and Grace Norman of the United States. Seely in particular would become instrumental in elevating paratriathlon, fighting for Paralympians to earn the same money as their Olympian counterparts for medal wins and serving as the first-ever paratriathlete to serve on the World Triathlon Athletes Committee.

The ongoing prize purse depletion throughout the 2010s eventually led to change and forced innovative thinking. Pro athletes still needed money and a platform, and the sport still needed more eyeballs (and participants). Super League Triathlon (SLT) debuted in 2017 with events in Australia’s Hamilton Island and Jersey, U.K. The premise of the fast-paced race series was to resemble the Formula 1 triathlon races held in Australia in the 1990s and early 2000s: high stakes, intense battles, with T.V.-ready racing in a variety of new and ever-evolving formats.

RELATED: What is Super League Triathlon, Anyway?

And it took about four years to get off the ground, but in 2018, the Professional Triathlon Organization formed. The organization, which represents the interest of non-drafting pros, has contributed funds to support races and athletes, with a focus on creating a series of events around a flagship race in the style of the Ryder’s Cup, called The Collins Cup.

The COVID-19 pandemic drastically changed everything for everyone, though, including triathletes. Race organizers and online platforms rallied to create race-like virtual environments, but none could truly replace the excitement of in-person events.

There were a couple of bright tri spots in an otherwise low point, globally, including the PTO 2020 Championship at Challenge Daytona in December of a very hard year. Paula Findlay and Gustav Iden took home wins and $100,000, all while putting on a compelling live show over the new 100K distance (a 2K swim, 80K bike, and 18K run) and heralding the return of major pro triathlon racing. And Super League Triathlon debuted its Arena Games in 2020, effectively mixing real and virtual racing.

Last year showed signs of growth coming out of many rough pandemic months. According to USAT, 100,000 new athletes joined, and participation is trending toward pre-pandemic levels. USAT representatives say they’ve also seen increased interest in the new Young Adult Membership for athletes 18–23.

Athletes had to wait a year, but the 2020 Tokyo Summer Olympics finally happened in July of 2021. Four-time Olympian Flora Duffy won her first gold in crazy tropical storm conditions, while Kristian Blummenfelt fought his way to the men’s top spot (he went on to win the Ironman World Championship in St. George in 2022). The mixed relay—a new event for Tokyo—was as exciting and competitive as everyone hoped it would be.

RELATED: The 8 Unforgettable Moments of the 2022 Olympics and Paralympics

Also in 2021: The inaugural Collins Cup finally got off the ground, and teams of 12 raced the 100K around Slovakia’s state-of-the-art x-bionic sphere as nearly 7 million viewers watched from home. Team Europe ultimately took the victory, but the 36 competing athletes all split a $1.5 million prize purse.

Jan Frodeno and Lionel Sanders went head-to-head racing an iron-distance exhibition on the roads of southern Germany, dubbed the Tri Battle Royale. And SLT hosted a four-race championship throughout September in London, Munich, the U.K., and Malibu, California.

In June, Kristian Blummenfelt and Kat Matthews competed in an exhibition event called the Sub7/Sub8 Project—they covered the iron-distance in 6:44 and 7:31, respectively, with the help of pacers, drafting, and other advantages not afforded to athletes in an open race. Similar to the Breaking2 marathon project, Sub 7/8 showed off what could be done without rules.

Also, Challenge North America has rebranded to Clash Endurance and plans to host a variety of events at speedways in Daytona, Miami, Watkins Glen, and Atlanta—with broadcast TV. SLT and the Collins Cup will continue to evolve and innovate in even bigger ways in 2022. And although the first Ironman World Championship of the year took place in St. George, Utah, the event should make a triumphant return to the Big Island this October.

The sport has come a long way since that race in Torrey Pines—where pros made just enough money to throw a small beach party. The Big Four never could have dreamed that exhibition races with just two competitors or a draft-legal race against the clock would ever capture the world’s attention or that triathlon itself would become an Olympic sport with two different events. They’d also probably never guess that the Hawaii Ironman would continue on, nonstop, until it would be interrupted for 30 months by a global pandemic—one that would see the sport hibernate, then reawaken in the years that followed.

The one constant in professional triathlon and its effect on the age-group experience? That things never stay the same.