Triathletes Are Experts at the Pain Game

(Photo: Getty Images, Erin Douglas)

Table of Contents

“You’re actually paying money to put your body through that?”

Every triathlete has heard a version of this statement from a confused, but thoroughly impressed, acquaintance. After all, triathletes are infamous for putting their body through the wringer. We often embracing discomfort in a way that’s foreign to mere mortals. We lean into pain because our sport requires us to, but also because we cherish the growth on the other side. We see this at every level of the sport, from age-groupers who push through to get a PR to pros like Kristian Blummenfelt and Lionel Sanders, who are known for laying it all on the line at every race, discomfort be damned.

So, what is it about our brain – and our relationship to pain – that pushes us in this way? Is there scientific evidence to support the common understanding that endurance athletes are capable of tolerating high levels of pain? Can we increase our pain tolerance? And if so, what happens when we go too far?

Let’s explore the neuroscience of pain and how it relates to the way we triathletes deal with pain.

What do we mean by “pain?”

Before diving into the cool science and how it applies to the multisport athlete, let’s get clear on a few definitions. First, what is pain? Pain is an uncomfortable sensation signifying that something may be wrong. It’s a tool that the nervous system uses to signal the occurrence of any injury. It actually evolved as a protective mechanism to prevent further tissue damage.

What is pain tolerance, then? Pain tolerance is the maximum amount of pain a person can handle before breaking down emotionally and/or physically. This differs from pain threshold, which is the minimum point at which a stimulus causes a person pain.

Good pain vs. not-so-good pain

Now, we’ve all experienced “good pain” and “not-so-good pain.” There are specific terms that are used to define that distinction.

Positive training pain is the “good” pain; the one that is necessary for improvement. In triathlon, this might include lung discomfort as you crank out climbing intervals, or reasonable muscle soreness that lasts a day or two. However, negative training pain may indicate that physical damage is beginning to outweigh the benefits. A good example of negative training pain is extreme muscle soreness that lasts four or five days. At this point, you become at risk of overtraining. As the threat continues to increase, you enter into more dangerous territory: negative warning pain. This type of pain signifies that an injury may be imminent. You experience more intense sensations that may be interfering with your regular training or your form mechanics.

RELATED: Every Triathlete Needs to Understand Good Pain vs. Bad Pain

How is the brain involved in pain processing?

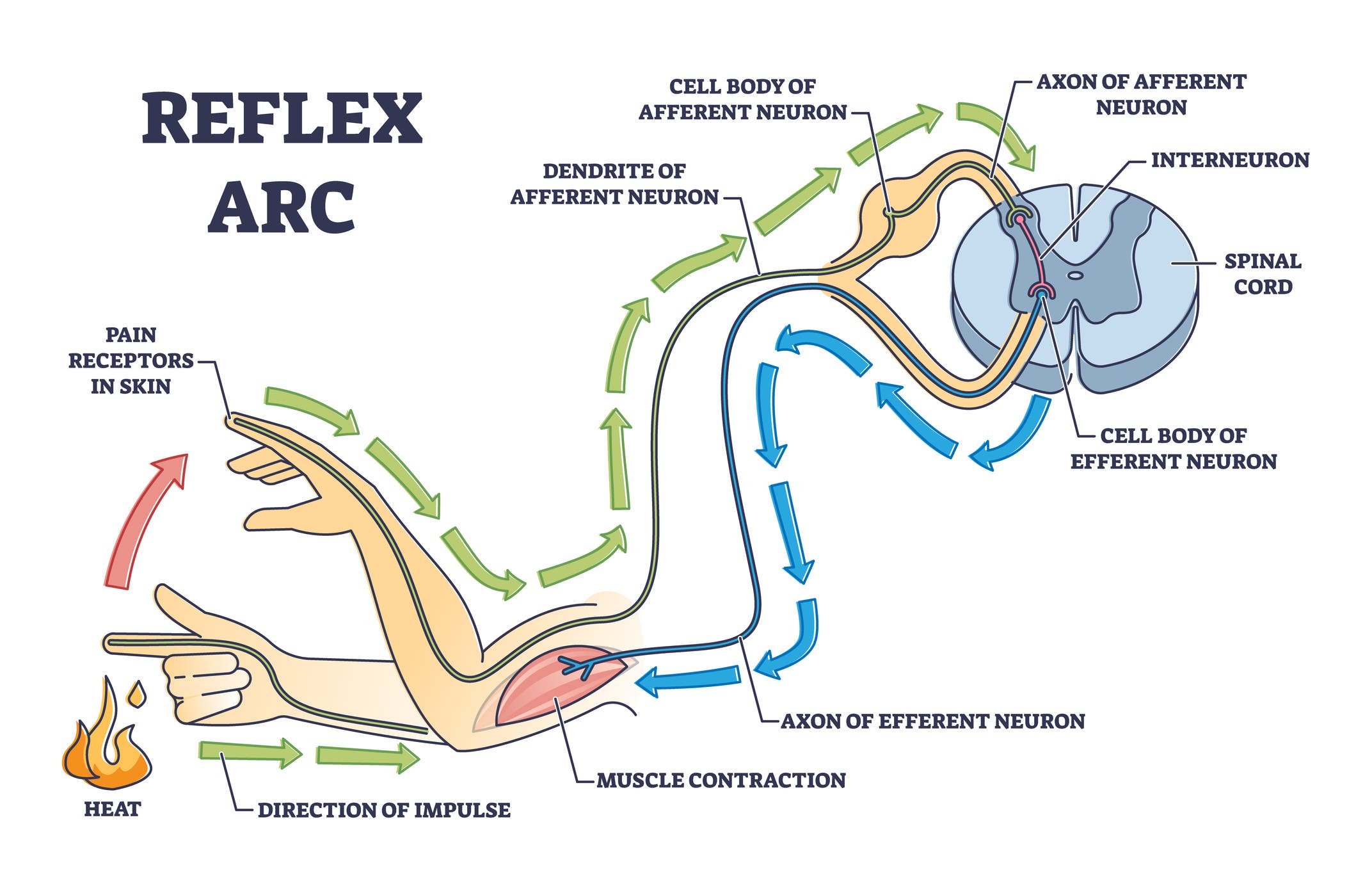

Most of the injuries we encounter while training or competing are relatively gradual, worsening over time. In those cases, the pain signal is sent from pain receptors throughout the body, through the spinal cord, and up into the brain. It is then processed in a variety of brain regions before a descending signal is sent from the brain, down through the spine, and into the peripheral nerves telling the body what to do.

However, some conditions are so urgent that your brain is initially bypassed. Consider running into the ocean for a training swim and stepping on a stingray. You would immediately retract your foot and avoid placing weight on it. That instinctive reaction happens quickly because the pain signal goes from your foot to your spinal cord, and then immediately back into the foot, telling it to pull back. Eventually, the message gets sent to the brain where you can categorize it in preparation for future incidences.

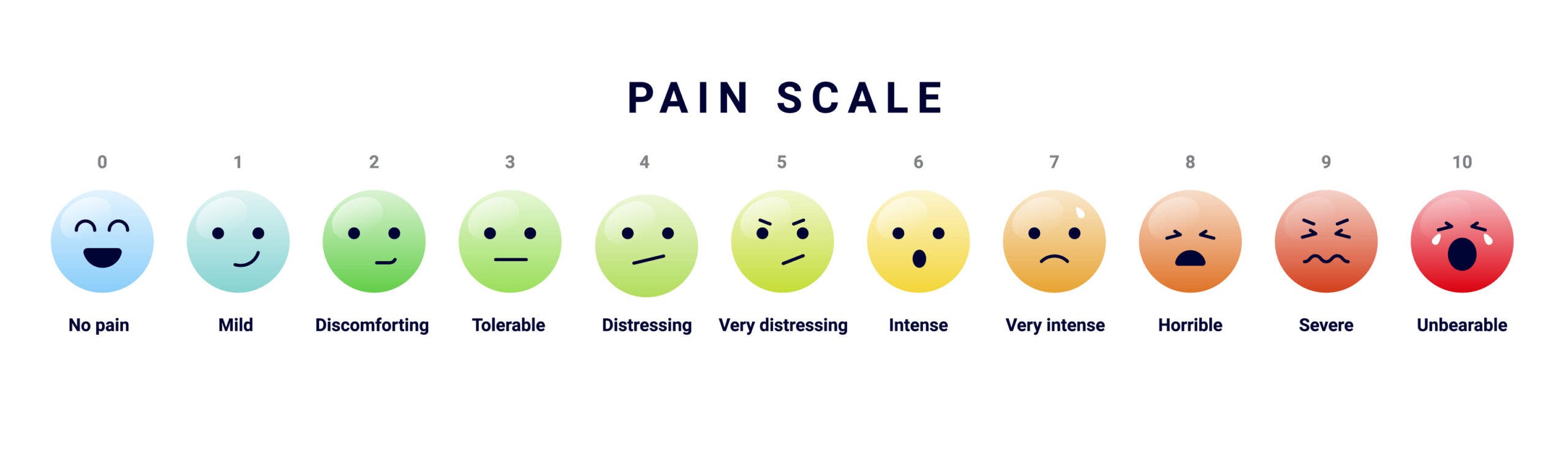

While pain has that neural basis, it also has a very large subjective component. This is where the psychology of pain enters the stage. Only you know the intensity of the pain you’re feeling, which is why doctors have to rely on self-reports, such as the 0-10 scale.

Not only does pain perception vary from individual to individual, but it also changes based on the particular circumstance. For example, you might feel terrible pain at mile 19 of a marathon, but somehow, you’re able to increase your speed and power through the last mile with relative ease.

Takeaway: Pain is processed in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), but your perception of it is influenced by a variety of factors, such as mood and adrenaline.

Fact or Fiction: Endurance athletes have a higher pain tolerance than other athletes

It should come as no surprise that there is, in fact, a quantifiable difference in pain tolerance and attitudes towards pain between endurance athletes and athletes of other sports. Some of this makes sense based on the type of movement. Endurance athletes perform repetitive motions over long periods of time, whereas strength athletes, for example, perform short bursts of activity. Researchers tested the difference between triathletes, weightlifters, and non-athlete controls. They found that both triathletes and weightlifters had a higher pain tolerance than non-athletes, but triathletes took the cake – exhibiting higher pain tolerance than weightlifters. Interestingly, triathletes were also less fearful of pain than the weightlifters. There’s that psychological component chiming in again.

Why are endurance athletes relatively unique in this way? Well, it could be that sports like triathlon, in and of itself, trains athletes to tolerate higher pain levels. We do know that aerobic exercise is one method for increasing pain tolerance, so this is certainly part of the puzzle. But, it could also be that triathlon attracts those who already have psychological tendencies, like a willingness to suffer.

Signs you need to “toughen up, buttercup”

There’s a good chance that you’re relatively comfortable with a certain amount of pain. You may even embrace the cliché that “pain is weakness leaving the body.” But, each of us has a unique relationship with pain that lies on a continuum. If you tend to be closer to the cautious end, pulling back before you’ve reached your edge, then you might want to think about where you can push yourself.

One way to determine if you can benefit from a boost in your pain tolerance is to evaluate your recovery. How quickly do you recover from hard intervals? How soon after a tough workout does your body return to baseline? If the answer is “pretty darn quick,” then you’re probably not getting uncomfortable enough. Another sign is to zoom out on your progress and examine if you’re improving steadily. Of course, improvement is not linear, but if you’re plateauing frequently, then you’re likely playing it safe more often than not. You might want to train your brain to increase your pain tolerance. Let’s get into that…

Can you train your body to tolerate more pain?

Before we can answer this question, we first have to know if pain tolerance is genetic. Pain tolerance is unique to individuals, but is it caused by nature or nurture? Well, it’s actually determined by a combination of factors, including genetics, stress, past experiences, expectations, age, and sex.

Since there are more than genetic factors at play, and since there is a psychological component, it should come as no surprise that pain tolerance can be somewhat trained. One way to increase pain tolerance is to do what you’re already doing: aerobic exercise. In fact, moderate-to-intense cycling training seemed to increase pain tolerance in one study. There are also two mental skills techniques that have proven effective to raise one’s pain tolerance: vocalization and mental imagery. You may already be in the habit of vocalizing your pain by saying “ouch” or cursing out loud. It turns out that these exclamations do actually improve pain tolerance, so feel free to keep at it. Mental imagery can change the relationship you have with pain and increase your tolerance of it. Try imagining pain leaving your body with each exhale; or, assign a color and shape to your pain, then mentally watch it transform into another, more neutral color that perhaps occupies a smaller area or a shape with softer edges. In fact, this technique is sometimes used by one of the most impressive pain management groups: expectant mothers during labor.

Another science-backed way to increase pain tolerance also happens to be an effective method of cross-training: yoga. In addition to the musculoskeletal benefits (e.g., increased strength and flexibility, which can help mitigate pain), there are also known emotional and cognitive benefits (e.g., development of non-attachment) that alter one’s perception of pain. In one 2014 study, cold pain tolerance was compared between yoga practitioners and non-yogi controls. Participants were asked to immerse their nondominant hand in a 41-degree F water bath until they could no longer tolerate it. They were, however, asked to remove their hand at 120 seconds if they lasted that long. This was repeated twice and tolerance was measured as the average time spent in the water. Interestingly, yoga practitioners tolerated this type of pain over twice as long as the controls. MRI brain imaging revealed that this significant difference may be partially due to yoga practitioners having a thicker region of the brain called the insular cortex, a structure related to pain processing and regulation. Also, yogis seemed to use different mental strategies compared with controls, such as relaxation, acceptance, and non-judgmental awareness of the pain. On the other hand, the non-yogi controls tried to distract themselves or ignore the pain. Lesson: It might be beneficial to lean into the pain!

Signs your high pain tolerance may be dangerous

Of course, it’s all fun and games until someone gets hurt. Increasing your pain tolerance so much can have devastating consequences. Let’s go back to the definition of pain: it’s a mechanism that evolved to signal an injury to your body. Sure, minor “injuries” like micro-tears are necessary to promote muscle growth. But, it’s important to know the difference between positive training pain (e.g., transient soreness and muscle fatigue), which indicates improvement, and negative training or negative warning training (e.g., intense soreness that lasts several days), which may indicate overtraining or a pending injury.

One sign to notice is if the pain causes a change in your form. If you cannot maintain proper mechanics due to the pain, even if you think you can tolerate the pain, then it’s time to back off. Another sign is to pay attention to the type of pain. Sharp, stabbing, or tearing sensations are almost never signs of growth. You may be able to handle it, but it’s not worth pushing through. Persisting in the face of this type of pain can cause chronic pain or force you to end your career, if not regulated.

The goal is really to embrace discomfort, but to back off when uncomfortable sensations give way to unceasing pain. While it’s been proven that mindset is important (e.g., having a fear of pain is positively correlated with a lower pain tolerance), it’s critical that you know not to push ahead at all costs.

Bottom line

Triathletes tend to have an objectively higher pain tolerance than other athletes. It’s probably a bit of a chicken and the egg phenomenon with endurance sports attracting people who thrive with discomfort, but also the aerobic exercise itself increasing pain tolerance. Ideally, build enough self-awareness to distinguish between positive training pain versus negative training pain, and learn the signs to determine if you can benefit from practices to increase pain tolerance or if you need to dial it back. The ultimate goal is both improvement and longevity, so move (and rest) accordingly.

Daya Grant, Ph.D. is a certified mental performance consultant (CMPC), neuroscientist, and yoga teacher who empowers athletes to get out of their own way and tap into their greatness. She swims, bikes, and runs in Los Angeles, where she lives with her husband and their young son.