The Key to Heart Rate Variability Might Be All in Your Head

(Photo: Getty Images)

If you’re reading this article, there’s a good chance that you’re wearing a watch, bracelet, or ring that has nothing to do with fashion. Like hundreds of thousands of health-minded people all over the world, you have jumped into the world of wearable devices that can offer insight on everything from stress to sleep to recovery through tracking physiological data like heart rate variability (HRV). You wake up each day and check your score, hoping to gain some insight about your overall readiness to train, but is there such a thing as a magic number? The truth is that though trackers can help us to understand how physical stress from training is affecting us, that’s only one part of the equation. Unless we consider how mental stress contributes to HRV, we may as well be wearing plain old jewelry.

RELATED: All You Need to Know About Training with Heart Rate Variability

HRV vs. Readiness Score

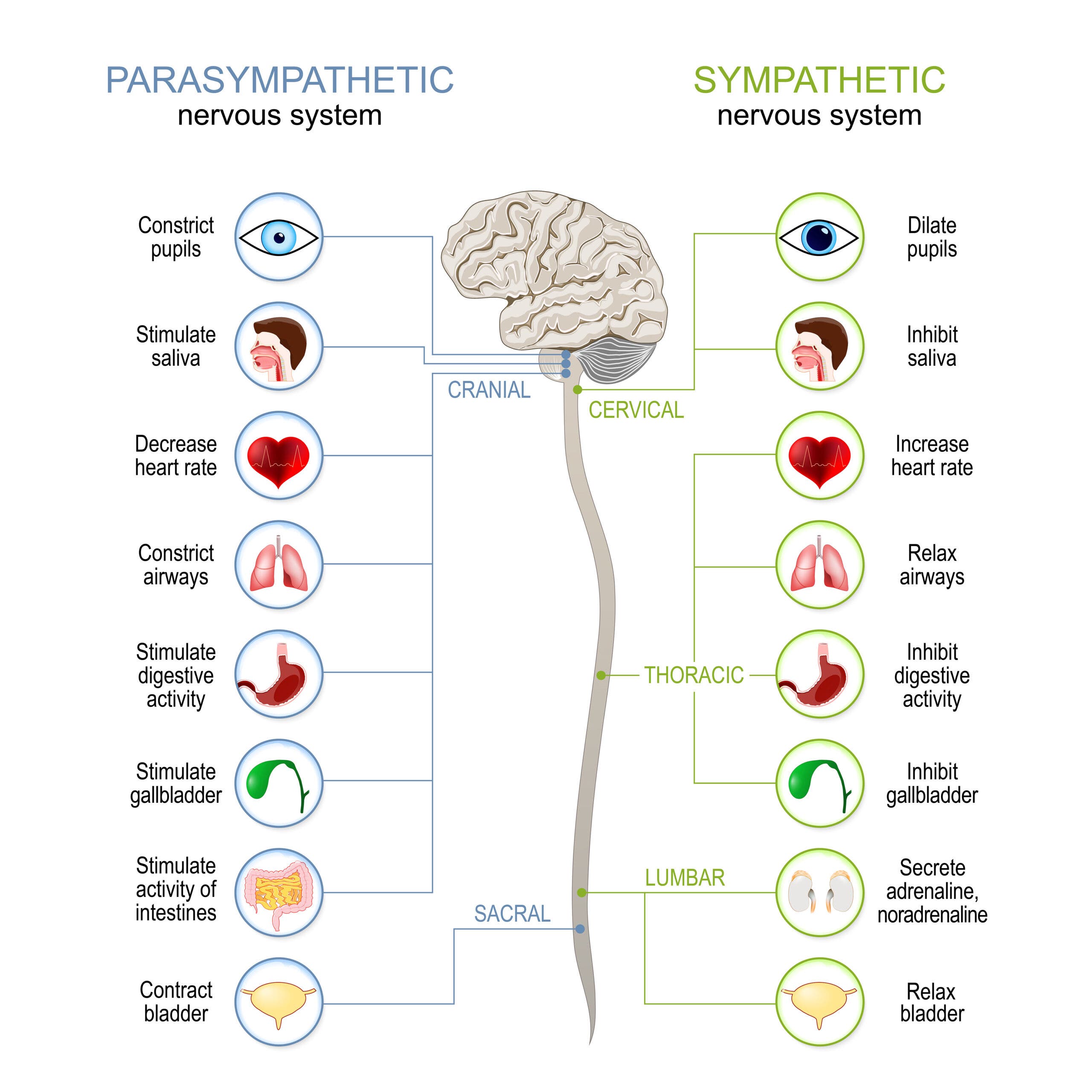

By now, you’re probably aware that heart rate variability is a measurement of the time periods between heartbeats. A higher HRV, meaning greater variability between the heartbeats, is desirable because it means that overall stress level is low. To understand how this works, we need a quick review of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The ANS contains the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) that will activate when a threat is perceived and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) which is responsible for bringing the body to a relaxed state when the threat is resolved. The ANS is responsible for regulating involuntary body processes, like the heart beating, in response to perceived environmental and psychological stress.

The variations in the heartbeat in response to stress are controlled by the ANS. Therefore, measuring HRV is a convenient way to understand when the body is experiencing stress, whether physiological or psychological. When HRV is high, stress may be low or we may be adapting well to stress. When HRV is low, we may have high stress or we may not be adapting well to that stress – it doesn’t really matter which, it just means we’re struggling.

In contrast, a “readiness” score from a device or app is a composite of many pieces of data including HRV. Although it is designed to give you an idea of your overall recovery and readiness to train, it is more of a consumer-friendly guide than hard science. To get more insight on all of this, I spoke with data scientist and athlete, Dr. Marco Altini. He said that the composite scores can be misleading because they include too many pieces of data, often muddying interpretation.

“They give the false impression that with more information, the score is going to be better, but then you don’t know if it is low because you did more or less of something,” Altini said. “Is it because your body responded differently? Are there other stressors that the system does not know about?”

Additionally, the devices interpret user data using the same algorithm, spitting out scores for athletes and non-athletes indiscriminately. Dr. Altini advocates sticking to the raw physiological data from an HRV measurement, but as we’ll learn, even that requires context.

What we’re missing about HRV

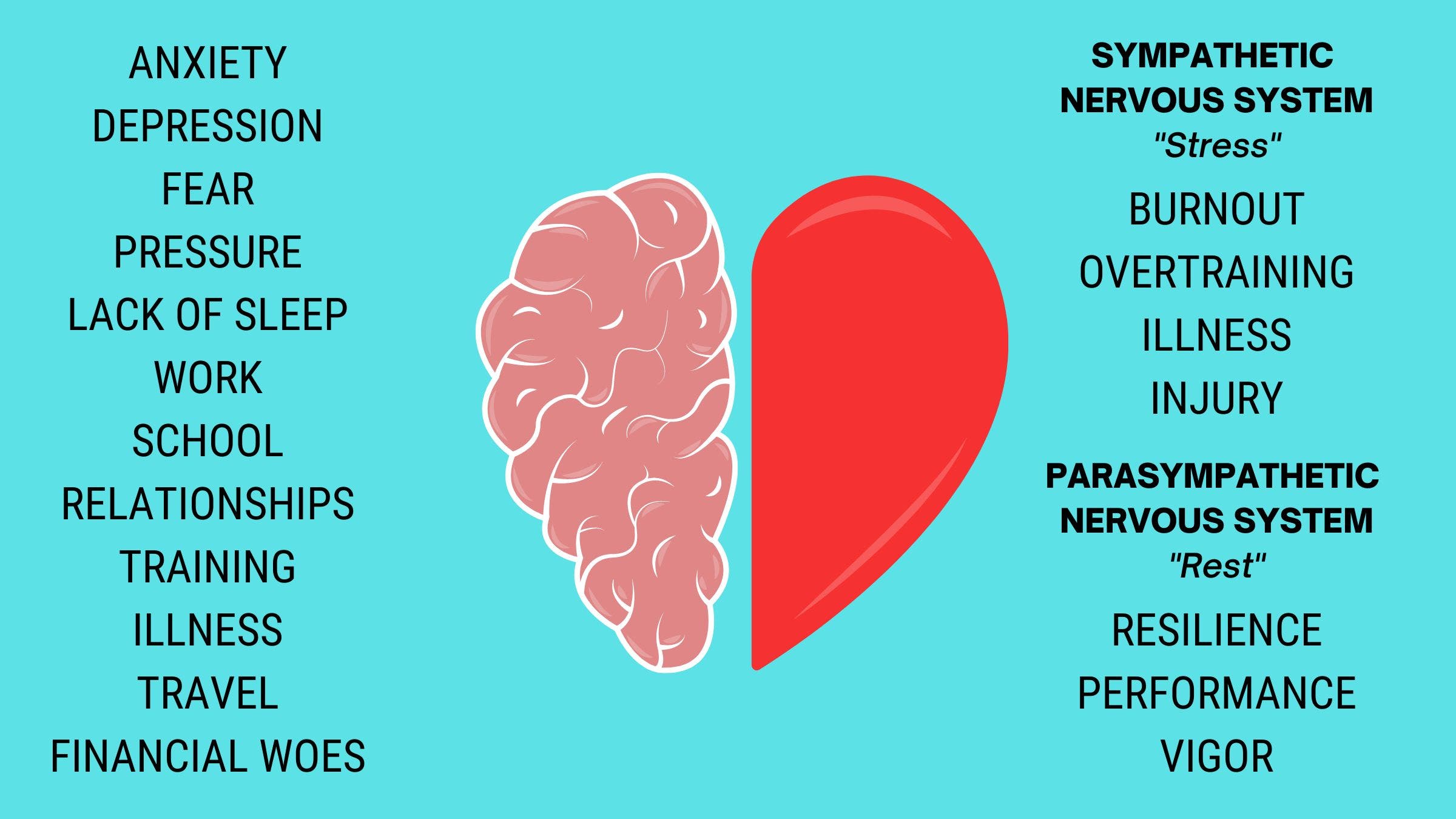

Remember that the brain perceives all stress, whether from physical or psychological origins, exactly the same. This means that changes in HRV reveal so much more than our potential for athletic performance–it reveals our mental health resilience. “In psychological research the one objective marker that we have is HRV,” says Dr. Altini, since it reveals what’s happening without words or actions. Research on mental stress and HRV draws a direct line between the heart and the mind, but Dr. Altini explains how this might play out in real life. “If we measure your data before you have to do something stressful that has nothing to do with training, like public speaking, we will see that your HRV is down and your heart rate is super high. You’re just sitting, but we can see that stress is impacting you regardless of the source, whether there is physical activity involved or not. ”This means that our ANS is impacted and our body is taxed, but we didn’t even run a step.

We can probably agree that this makes sense, yet putting that knowledge into practice can be tricky for many athletes. When we look at a lower-than-normal raw HRV number, we likely reflect on whether or not we can pinpoint the source of the stress. Athletes will typically scan their recent training log to see if there have been a number of high intensity training and racing recently. If we do not see anything out of the ordinary, we will likely ignore the low HRV and do our planned training anyway. But, we’ve missed out on half of the investigation.

Dr. Altini says that it’s not always about the training, at all. Athletes need to consider the psychological stress coming from work, family, lifestyle, even food and alcohol intake – and still alter their training plans. A low HRV means the body is taxed, no matter the source, and our body is in need of rest. If we train hard anyway, research on the body’s adaptations to training stress shows that our physiology may not respond positively in those moments. Instead of “pushing through,” we’re likely detracting from our athletic progress.

How honoring HRV might improve performance

Instead of literally running away from your HRV score, Dr. Altini explains a more savvy way to engage with the HRV data. It’s true that the body needs a certain amount of stress with adequate recovery, but timing is important. HRV can play an important role in determining when and how to hit the gas pedal. In a study of endurance runners, half used HRV to govern their training decisions, skipping hard sessions in favor of easier runs when their number dropped.

It’s important to note that the origin of the stress that led to the lower HRV was not relevant. The other half used a traditional training plan that included all of the high intensity sessions, no matter what. At the end of the study, the HRV-directed runners did fewer hard training sessions and their bodies were less taxed, yet both groups had significant improvements in VO2 max. The take home message? In a sport like triathlon where overtraining is a significant threat, HRV-directed training might keep athletes from overtraining, yet still yield performance results.

Practical ways to engage with HRV data

To have the best possible experience with attempting to use HRV for training, it’s important to follow some basic best practices. All of the following suggestions are based on using the raw HRV data, not the composite scores. First, try to use a measurement of HRV taken first thing in the morning. Devices may gather data at different times, but both research on athlete fatigue and Dr. Altini’s extensive studies show that if you are seeking insight on overall load of stress, a morning reading is best. Second, be prepared to gather data for several weeks before trying to interpret the information. Make notations about nights when you had a few extra drinks, weeks where work stress was particularly high, days when you were worried about bills, and any other psychological or lifestyle factors. This will allow you to see how you respond to periods of higher and lower training intensity, higher and lower periods of lifestyle stress, and for women, will include an entire menstrual cycle of hormonal fluctuations.

Next, resist the urge to compare your data to anyone else’s. We have all seen those “average HRV by age” charts online, but the truth is that the most insightful comparisons come from within your own data. Stress is deeply individual and as Dr. Altini explains, what your body and mind perceive as stressful is going to be different than other people, even if they are training and living in generally the same way.

“It’s never the stressor, it’s how we perceive the stressor,” Altini said. “This will impact the autonomic nervous system. If you think of something as stressful, you’re going to be stressed.” And no, perceiving more stress than someone else does not mean that you’re weaker. It means that your ANS is more activated, period.

Finally, resist the tendency to give more importance to physiological stress over psychological stress. Be prepared to view the data in the context of your whole life, not just your athletic life. Those psychological stressors have a greater impact than we may want to admit, but there may be a silver lining to paying attention.

RELATED: Life Stress, Work Stress, Training Stress—Your Body Can’t Tell the Difference

“For athletes, it’s a good thing because even if HRV data is picking up psychological stress, they can manipulate training and still get a positive effect,” Altini said. This means that there is no downside to backing off intensity, whether you’re comfortable with the origin of the stress or not.

Be your own scientist

Let’s be real, triathletes are typically eager to jump on the high tech ways to improve their performance, but might be less likely to believe that their mental status contributes to the data. If you’re not convinced, do your own experiment on yourself.

Dr. Altini often uses himself as a test case since he often struggled with overtraining and injury in the past: “My own data shows that what creates deviations is periods of high stress from work. HRV doesn’t get suppressed when I train more or train harder, only when I have that psychological stress.”

He has learned to incorporate more low-intensity sessions and rest days in these periods and has experienced less injury as a result. If lower intensity sessions help the body recover, no matter the source of the stress, you can’t really go wrong. Sounds like a real no-brainer.

RELATED: How Do I Know if My Recovery Sucks?