Executing Your Race Strategy: The Bike

(Photo: Getty Images)

Races are the exciting part of your journey, an opportunity to put all of your training, focus, and intent into action. After months of dedicated, hard work amid the rest of your busy life, you have the chance to execute your goals. Although you might prioritize training around specific races (A versus B races), any race is a chance to prove your mettle on the racecourse.

You must have a race plan, but you can’t expect everything to go according to that plan. Even in training, things go wrong or differently. Ultimately, you must execute a race with the cards you are dealt that day. A wide variety of situations can come up, and you need to be poised to respond.

Bike Course

Ride the main parts of the course and consider driving the entire route, if possible. You don’t need to ride the whole course, and whatever you do before the race, it shouldn’t deplete you. It’s always less stressful when you see something for the second time and you know the way. If you become somewhat familiar with the course, your focus can be on terrain management and pacing instead of looking at the road ahead and asking how long before the next turn. Knowledge is power, allowing you to focus on what will return your best speed relative to your distribution of work and effort.

Executing the Bike

When you first get on the bike as you are departing T1, you go from your highest heart rate to your highest likely level of stress. This is precisely why you want to use the first 10–30 minutes or so of riding to settle down, get comfortable on the bike, and focus on the task at hand. Ideally, this will be an extension of the habits you built in training: namely, riding your bike well.

For the initial period on the bike, focus on good cycling habits: establishing good pedal mechanics and maintaining a nice, supple posture from the tips of your fingers all the way to your toes. Keep your elbows, shoulders, and ankles loose so that you become one with your machine. If you practice this and it becomes habitual, it will be easier to implement during a race even though you’ve just completed the swim. Let your stomach settle for at least 20 minutes into the ride before you start your fueling strategy.

I train athletes to develop an internal pacing mechanism rather than targeting a specific power output or heart rate in an Ironman or 70.3. This allows you to be in tune with your body and maintain a good sense of strong effort, strong enough effort, and too strong of an effort throughout the race. Power output or heart rate might provide a baseline framework, especially for athletes prone to overpacing, but overemphasizing metrics can also diffuse your natural strength and paralyze your intuition. Furthermore, power output is easily influenced by the variables you face on race day (terrain, wind, temperature, altitude, humidity, etc.). Ultimately, the best athletes are riding the fastest, as opposed to producing the most power.

Pacing with Power

Many coaches tell you that on the bike portion of the race, you should simply plug into race power. The assumption is that if you hit your power target, you will maximize your race potential. By way of reference, the most common race efforts are promoted as:

- Ironman bike racing: 70 to 80 percent of functional threshold.

- Ironman 70.3 bike racing: 80 to 95 percent of functional threshold.

Note in both cases, the longer the ride takes, the lower the target will be. Although there is nothing wrong with shooting for a range of power that you can safely sustain, such a framework is not the whole story of triathlon bike riding.

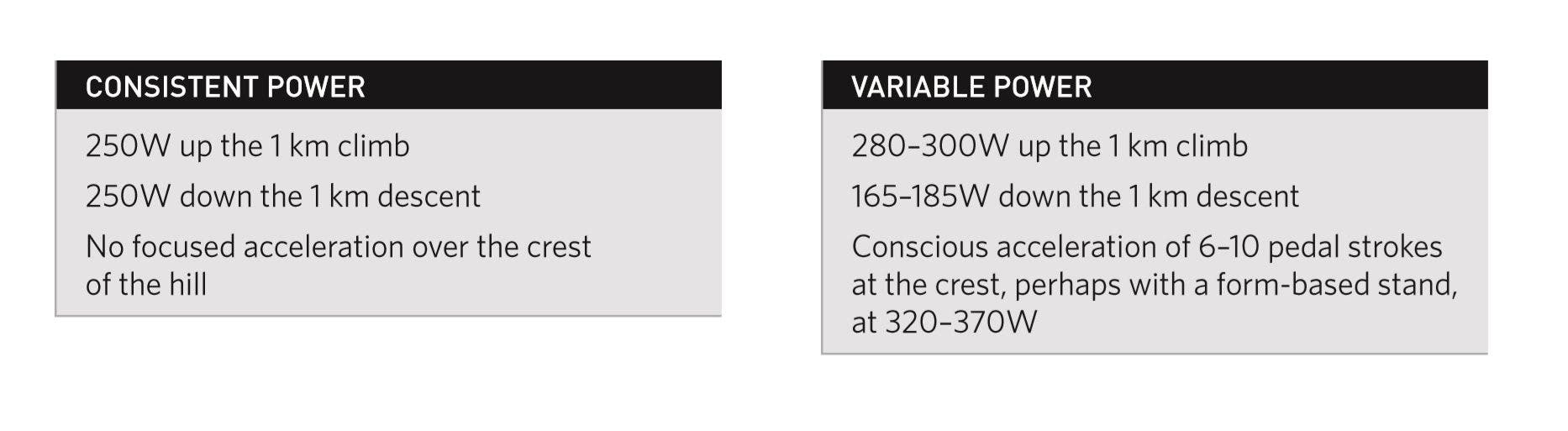

For example, if a stretch of the road was consistently 5% uphill for 1 kilometer, then consistently 5% downhill for 1 kilometer, maintaining the same power uphill and downhill would not yield your fastest time. The grade on the uphill makes the production of power easier for most riders, and the speed return is great for little extra work. In contrast, forcing yourself to maintain the same power output downhill will cause metabolic stress with limited returns on the effort. The faster you go, the more work is needed to add incremental speed. The same law of diminishing returns goes for your cadence; it wouldn’t be efficient to ride the same cadence over the 2 km distance. We haven’t even begun to discuss the more valuable 6–10 pedal strokes athletes would deploy as they crest this hill to gain momentum and accelerate over the top. Although you might not experience a stretch of road just like this one, the example isolates the issue, giving us an opportunity to evaluate two different approaches to executing the ride.

In this example, the variable power scenario is significantly faster, perhaps up to 30 seconds over the course of the 2 km. Of course, the terrain on a racecourse will not be so clear-cut, but imagine repeating shorter hills like this many times over rolling terrain. Over the duration of the entire race, your average power output might be lower, taking into account the relaxed output going downhill, but you will likely go a lot faster over the distance. To properly execute this strategy you must be specifically trained, adopt proper form and technique, and be focused enough to apply these skills to the actual terrain.

These concepts are tough to coach, especially remotely, so most coaches and writers simply return to overall output. Retaining power output up and down a grade is called flattening the course. If you were to apply this approach to the Ironman World Championships, you would either leave a lot of unused speed on the course or blow your energy with high effort going downhill.

Power Output on the Racecourse

To successfully use a power meter in a race, you need a solid understanding of how different terrain and conditions affect power output.

Different Grades

Athletes often have their own favorite grade, which allows them to generate an optimal power output for a given metabolic stress. If you ask any rider to perform a best effort time trial on flat terrain, then repeat the test on a smooth grade, the flat terrain will always produce less power. This means that holding the same power on the flats as you do on a grade isn’t the fastest way to navigate the terrain.

Headwinds and Tailwinds

If you are sitting on a stretch of road with a strong tailwind, you will typically find it more challenging to maintain the designated power output than if you were riding in the opposite direction. Interestingly, retaining the high-power output with a tailwind typically nets minimal reward in terms of speed. Every 0.5 mph of speed you try to pick up will require disproportionately more power. If you hold your power output, you have a high risk of riding below your potential in headwinds and overworking in tailwinds with little speed to show for it. At the end of the day, efficiency will help you ride faster and run well off the bike.

Rolling Terrain

Imagine a piece of rolling road with an uphill grade, a crest, a small descent, and finally a valley at the bottom leading into the next roller. Holding a tight power output range throughout this piece of road is not the fastest way to navigate this all-too-familiar stretch. If you instead push just above any power level heading up the grade, accelerate the bike over the crest of the hill with a small ramp up of power and/or cadence, then carry that speed down the back side of the roller and maintain it through the bottom of the valley, you will gain maximal speed over the stretch of road. Review your power graph when the ride is over, and you will see small surges of power that create acceleration.

Ultimately, a cycling power meter is a great tool, but it is just that, a tool. It doesn’t govern you or your riding, and using it successfully requires a real understanding of how different conditions and terrain will affect your power output. All of these scenarios require time in training to develop the skills to navigate terrain and conditions as efficiently as possible. So, you can use metrics as a framework early in the race and use them as a motivator later in the race, but you should never lose sight of the other intangibles.

Terrain Management

When it comes to the bike segment, one of the most important things you can do is to break the course down into sections. The ride constitutes the longest portion of the race and can be emotionally draining. Throughout the race, we prioritize process over outcome, and on the bike you can break it down to riding the bike well, listening to your intuition and managing feedback, and monitoring your fueling and hydration.

Remember to ride the bike well in the last quarter of the ride (that means sitting on the bike well, pedaling the bike well, managing the terrain well), and you’ll be closer to your trained potential and less susceptible to muscular fatigue.

Most athletes see their power output dropping along with their speed and panic. They’re chasing power levels, unaware that they’re not sitting on the bike well, not pedaling well, and not managing the terrain well. Speed and efficiency are the result of riding the bike well. Double down on doing all of the little things right and stay in the moment as opposed to judging yourself, and you will maximize your speed potential.

Fueling and Hydration on the Bike

Your fueling protocol starts on the bike. To review, at 20, 40, and 60 minutes, take in 50 to 100 calories with water. At 10, 30, and 50 minutes of every hour, hydrate with a diluted electrolyte solution. An optimal solution has less than 4% carbohydrate with some electrolytes. From there it’s about self-management; you have to be aware of your condition. If you are getting dizzy or weak or losing focus or motivation, you are calorie deficient. If you’re 20 minutes into the bike segment, and you’re feeling very weak, don’t just hydrate; take in more calories because your body is asking for more. After your energy comes back, move to more hydration. On the contrary, if you start to burp and feel a little bloated or sick, don’t keep piling in calories; drink your beverage so you can dilute the food in your stomach until it can be absorbed.

Transition 2

Just as you did at the end of the swim, you should start to prepare yourself for T2 when you’re near the end of the bike segment. For a 70.3 race, this begins with about 5 km to go; in a full Ironman, it’s around 10 km to go. In both cases, you want to get your mind and body ready for transitioning to the run. The first step is to back off the intensity just a bit. That might mean letting your pace slow to 19 mph if you’ve been charging at 20 mph.

In addition, start to check in with yourself and think about where your body is tight and which muscles you need to loosen to be ready to run with good form. You can stand up out of the saddle a bit and cruise, stretching your hips, calves, lower back, shoulders, and neck. Otherwise, keep pedaling with good cadence and form on the way toward the bike finish. Also, do another check on your fueling and hydration needs: Do you need more calories? Are you feeling lightheaded or bloated? Do you need more hydration to clear your gut before you start to run?

As with the end of the swim, when you’re moving into the transition you want a strong mindset going into T2. Think about precisely what you’re going to do so you’re as ready as you can be and not under duress. Focus on being calm and collected as you dismount your bike, carefully jog your bike to the rack, remove your helmet, and change into your running shoes, hat, and sunglasses. Feel free to execute some basic stretches or whatever works for you to help you feel good. The goal is to ramp up to your running potential as quickly as you can when you leave T2. Avoid taking in any calories, but drink some water and then head out on the course.

Read On

Executing Your Race Strategy: The Swim

Executing Your Race Strategy: The Run

Adapted from Fast-Track Triathlete by Matt Dixon with permission of VeloPress.