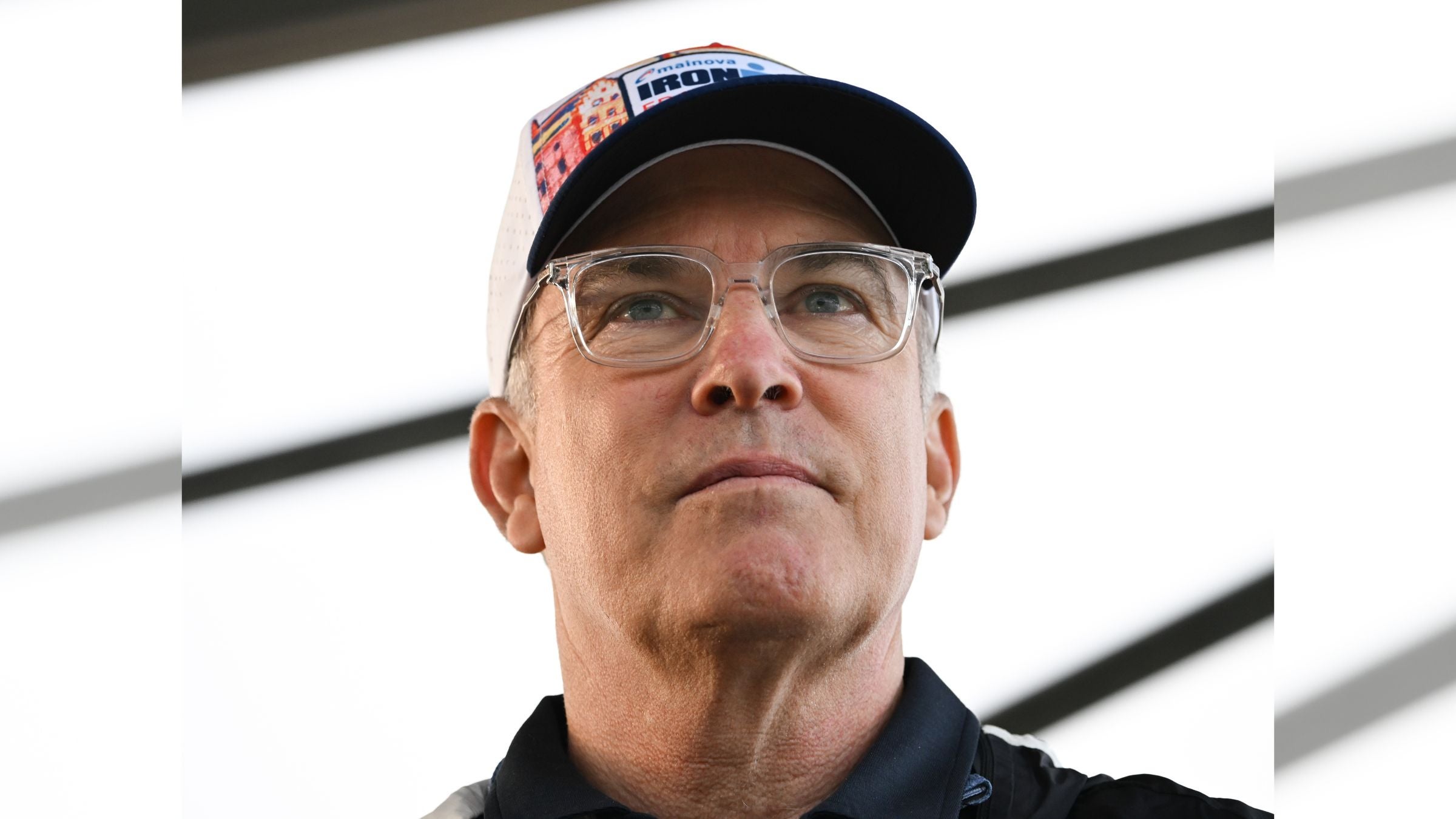

Andrew Messick Talks Retirement, Split World Champs, and More

Andrew Messick will retire from his role as CEO of Ironman in 2023, after a search for a successor is complete. (Photo: Arne Dedert/dpa)

After 12 years in charge, Ironman chief executive officer Andrew Messick announced his retirement last week. But what prompted arguably the most influential figure in triathlon to take the decision, and what kind of a legacy has he left? Triathlete caught up with him at home in California to find out.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Triathlete: What prompted the decision to retire, and why now?

Messick: It’s been in the works for a while. I started talking seriously with my board at the beginning of the year. Coming out of the pandemic was an extraordinarily difficult time for us and every other event organizer in the world.

It’s bittersweet, that’s for sure, but in my head I realize that it’s the right thing to do, and if I don’t feel I’ve the energy for the next five years, I should pass the baton to somebody who does. But the act of passing the baton is never ever easy. I’m about to turn 60 and have spent most of my professional career on the road. I have responsibilities to my family, my mom. Do I really have it in me to do five more years up to my eyeballs? I concluded I don’t, and the business deserves somebody who does.

You talk of the next five years. Is that because there’s a planned change of direction for Ironman?

That’s how long it takes to do a lot of things we want to do. We’re a company that has historically been organized around events and spend all our time thinking about how Frankfurt, Hamburg, Bolton or Wales is doing. Or Cape Epic or UTMB. Our future is not to think less about events, but more about our customers.

When I walked through the door in 2011, we didn’t know how many people were doing Ironman races. I could tell you chapter and verse about Ironman France, but we didn’t have a database of athletes. The future is more about how many customers we have and how good we are at retaining them. We need to pivot towards customer centricity and that’s a long journey that needs different IT systems, marketing approaches, and a lot of things that need to be implemented.

That’s just one example of how a broad base change program for the company is really important. If it’s going to take five years, do I want to start something important that I’m not going to see through to the end? I don’t think that’s fair.

Did the tragic circumstances surrounding Ironman Hamburg – and either any mistakes that were made or the emotional toll it must have taken on the team – have any bearing on the decision to step down?

The answer is yes. The original plan was to announce my retirement the day after Hamburg, and instead we’re announcing it during July 4th week, which for an American company is a weird time to do it.

We were ready to go [announce the resignation] and then what happened in Hamburg caused us to postpone it. The cake was fully baked, but it wouldn’t have been appropriate given the tragedy of the situation in Hamburg to tell my story at the same time.

While stepping down as CEO, you will be on the Ironman board. What will your role be?

I’ll be CEO until the new person comes in, and do whatever is needed to help them. It could be as little as providing a pat on the back, or there might be parts of the business where they want me to be more involved. We’ll cross that bridge when we get to it. In terms of staying on the board, with my knowledge of the business and understanding of the ecosystem, I’m pretty confident that I can contribute for a while.

Reflecting on your 12 years as CEO of Ironman, what will be your proudest moment?

I think we’ve done some marvelous things in my tenure. We’ve done some things I think are farsighted and good for the brand in the long term. Number one, the decision for the Ironman 70.3 World Championship to rotate, and to ultimately grow that race – we have 125 qualifying races – into clearly the second-most important race in the world right now. When I joined, we had never had a world championship outside of the United States.

To rotate it every year and grow it into a two-day event that has 7,000 athletes has been really good for the growth of the Ironman community. We’ve got 100 athletes from Chile, 140 from Argentina, 70 from Bahrain…it has become a real global celebration of racing, and I think we got that right.

Number two, we’ve expanded the brand a lot and have pushed aggressively and hard. In South America, we only used to race in Brazil. Now we have Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, Argentina and Uruguay. In the Middle East and North Africa, we’ve races in Morocco, Egypt, Dubai, Bahrain and Qatar. It went from nothing to a region where there are super motivated pools of Ironman athletes. We’ve seen the same in Eastern Europe with Poland, Estonia, Croatia, Slovenia and Kazakhstan and the Far East with Vietnam and the Phillipines. In all those places the races may have started out full of expats, but there are now fired-up local triathlon communities that did not exist before and they believe in Ironman the way we all believed when we started out.

Third, I’d say women in general. That includes giving women their own day at 70.3 worlds in 2017 and being able to World Championship races where women get the full spotlight. However hard you try in a race that has men and women, the bulk of the attention is going to be on who is at the real front of the race. We’ve grown female participation a lot over the years. In North America, we have 70.3s that are more than 40% female and Ironman races that are 30% female, and that’s a transformation. It hasn’t happened by accident – it’s been a real focus.

What’s the most challenging moment you’ve faced?

The Hamburg situation was super difficult, there’s no doubt about it, but I think the hardest situation was the pandemic. When you are an event company that doesn’t do events, you’ve got problems.

In 2020, our revenue relative to expectation dropped 85%. We have employees whose families need to eat and have mortgages to pay. That was the most difficult time because we were trying to survive. A lot of people in the event industry didn’t, but we kept the organization together.

Regarding Kona, we were super unlucky. We knew that we were making a bet when we announced two days of racing in Hawaii in 2023 before we had executed 2022. That’s the way the qualifying cycle works. We had the support of the island, our athletes and everybody, but it turns out we were wrong about the Big Island’s willingness to support two days of racing. That left us with this super unattractive set of options around how you handle the world championship. We promised all of our athletes that they were going to race in Kona in ‘23, and we promised women they were going to get their own day of racing. And we couldn’t keep both promises.

That’s what led us to Nice and Kona and I hope that is a decision that will age well. We think we’re going to deliver a great experience to our athletes, but it was a very very challenging tie for us.

RELATED: An Exclusive Q+A With the Race Directors of the Ironman World Championship in Nice

With a few months having passed since that decision, do you still believe it was right to split host locations and commit to it until 2026?

It’s largely unfolding the way we expected. We knew slots were going to roll and roll pretty deep, but we’re confident the world championship will be as competitive as it’s ever been. The people at the front of the age groups are taking their slots, and there are many more slots, so they are rolling a lot farther than they have ever rolled. We expected that. But in terms of the ability to win your age group, it’s going to be harder than it’s ever been, for both men and women. Instead of being 50 women in a particular age group, there will be 200 but the top 20 will be better than they’ve ever been. So the fastest people in the world are going to be there, but there are going to be a bunch of people in that race who wouldn’t otherwise have qualified and we knew that was going to happen, and we’re OK with that.

No one feels great about the atmospherics of slots rolling a long way, but I think that’s going to change in a couple of years. We’re going to have 2,000 women race in Kona, up from 850 in 2019, which was the most women ever. Are there enough women racing in the world to have 2,000 outstanding athletes in Kona? Yes, for sure.

I think the bet we’re making on women’s racing is the right one, especially in this day and age. Look at the last 12 months: the women’s rugby World Cup was an unprecedented success as was the UEFA women’s European Championships. We’re in a real moment for women’s sports, and the upcoming women’s soccer World Cup is going to break every record for attendance.

Giving women their own day is consistent with how we’ve treated women from the beginning. When women starting racing Ironman in 1979, there was no women’s Olympic marathon, no women’s UCI road race, and longest women’s swimming event was 400 meters. Ironman didn’t care. There has never been a time when the distances and cut-offs were different for men and women or the pro prize money was different for men and women. Women are going to get their own day, and that’s going to help, reinforce, and drive women’s participation in endurance sports.

Trying to fill Ironman World Championship spots brings into focus how many triathletes you should have on the race course. Ironman is for-profit, but there are also concerns over safety, congestion, and watering down the value of a world championship event. Do you think you’re striking the right balance?

At any world championship, there’s a relatively small subset of people who are racing for the world title. For a lot of people, just qualifying is an honor. We’ve always had a system where wacky roll-downs happen and a slot will roll down to the 50th place. Until eight years ago, we had a lottery for Kona and people didn’t get wound up. Nor do they get worked up because there are legacy athletes [athletes who qualify for the Ironman World Championship by completing 12 or more Ironman-branded races] there. And there have always been people who finish close to midnight, and by definition, with the exception of the older age groups, those are people who didn’t have a very fast day. Back in the old days, the race had a 24-hour cutoff, and being super fast is only part of it.

But the criticism isn’t just about slower athletes qualifying for a world championship – it’s about too many people on the course in general. Making drafting almost unavoidable, for example.

Race course density is, to a large extent, a function of how you start the race. A mass start means a much more congested bike course, and in my tenure we’ve moved almost completely to rolling starts. Part of the reason is to decrease density on the bike course, and I think it’s a better, fairer and safer experience for athletes.

RELATED: Do Triathletes Really Want To End Drafting?

When people rail against Ironman, they tend to rail against Andrew Messick? Is it fair that the buck always stops with you?

I don’t know if it’s fair, but it’s part of the job and what I get paid to do. Being the CEO is always a lonely job and that’s part of what you sign up for. I wish I could say that the criticism doesn’t bother me, especially when the criticism isn’t necessarily fully informed or fair, but I am a human being. Yet the last thing you’ll hear from me is that you really ought to feel bad for the CEO. There are parts of the job that are difficult, but there are parts that are awesome. On balance, I’ve loved sitting in this chair.

I take consolation from the fact that everyone in the company is helping these remarkable athletes complete incredible journeys. We don’t always get everything right, but it’s a group of people who are unbelievably dedicated to helping the community fulfill their goals. I don’t want to say it’s noble, but it’s meaningful, and everybody in our company could find an easier way to make a living, yet they choose to do this. Despite everything, it’s been a pretty cool job.

Not everybody is on staff, and Ironman also relies heavily on volunteers to put on events. How have you managed what must be delicate relationships at times?

Volunteers are a really meaningful part of the race ecosystem everywhere in the world, and that extends beyond triathlon. Volunteering is also fun and there are a lot of people that really enjoy it, so we need to continue to cultivate volunteers and make it a positive and rewarding experience.

Over the years, our foundation has donated millions of dollars to these communities who support our races, and a lot of those people volunteer at our races. It’s a very positive association.

No one could run races [without volunteers], it’s not just us. You need the support of the community.

Jumping back to the start of your tenure, how do you reflect on the LiveStrong partnership that meant Lance Armstrong would be racing Ironman with a view to challenging at Hawaii? [Armstrong was subsequently banned by USADA before competing in his Kona qualifying race]. Given your experience now, would you handle it differently?

The Lance Armstrong story is interesting and unique. It isn’t really a celebrity story because Lance was the greatest 16-year-old triathlete in history. There has never been a better young triathlete than Lance Armstrong, who was racing pro in high school and slugging it out with Dave Scott and Mark Allen.

This wasn’t the story of us jumping into a relationship with an athlete from a different sport who decided to dabble in triathlon. The fact he started as a triathlete really mattered and everybody was really curious to see how good he was going to be. But he got the penalty from USADA and we’ll never know. Maybe USADA will change their position and he’ll be eligible to compete in our events at some point in the future. He was a terrific swimmer, the man could ride a bicycle, no doubt, and he was a pretty decent runner. And who knows how good he could have been.

It sounds as if you’ve quite a warmth for Armstrong. Would you like to see him compete as a age-group triathlete in Ironman?

We’ve never taken a position on any athlete. As WADA signatories, an athlete is either eligible or ineligible, and right now he’s ineligible. There are plenty of athletes who have, in triathlon or other sports, served penalties, come back and raced, and in some cases won championships, and as a race organizer who has agreed to the rules of the WADA code, my personal beliefs and feelings are irrelevant.

Even now that you’re stepping down?

I mean, I’m a bit of a liberal and a lefty and believe in redemption, and believe if somebody has paid their debt to society – whether it’s doping or whether someone has committed a crime – they deserve the opportunity to live their life to the best of their ability.

I feel that way about people who have in many cases committed doping offenses, particularly cyclists from that era and I was involved in the cycling industry in that era. I think it’s worth pointing out that there are a lot of people who did what they did, paid their debt and have gone on with their lives. I’m not going to be one of those people who says I wish them eternal damnation. There are other cases I think are more egregious, but what I think doesn’t matter, so who knows.

Sticking with anti-doping, there have been allegations through the years that Ironman hasn’t done enough. Following the Collin Chartier incident [Chartier was caught by Ironman’s testing protocols], there’s been the counter argument that Ironman often wanted to do more to sanction cheating but was stymied by athletes’ appeals. Is that something you can comment on?

We have agreed to the WADA code, and the WADA code has obligations for us to test that we take seriously, and it has a lot of protections for athletes, and rightly so. For all the right reasons, there are defined mechanisms by which athletes’ rights are supported, and the standards that we or anyone else needs to achieve to convict someone of an anti-doping rule violation are high. I believe in that 100%.

An athlete has a relatively condensed professional life, they rely on sponsorship, and to be a doper means you’re not racing for a number of years and have a taint that’s hard to remove. So, you have to be able to prove it, and proving it is hard. We don’t shirk from that and we test and catch and prosecute people, and have always done it. And there isn’t anyone else doing what we do.

If people say Ironman is not serious about anti-doping, then compared to whom?! There’s no one else in long course triathlon doing anything. It’s us, and it’s always been us, and that’s the way it is. And there’s been plenty of other opportunities for race organizations to partner with us and piggyback on what we’re doing, but it’s expensive and it’s painful and you have to have the will to take it to the very end and prosecute wrongdoing, and not everybody has that appetite.

RELATED: Doping in Triathlon, a six-part series

Have you been frustrated in attempts to sanction high-profile athletes?

Absolutely, we have taken cases all the way to the court of arbitration for sport and lost, and these are people we believe we had cold. And those cases will never see the light of day. You will never know who those athletes are, and that is the right answer because ultimately you have to protect the rights of the athlete, and if you can’t prove it then tainting them by association is just wrong. And let me reinforce that [not getting the conviction] is personally unsatisfying.

Was there an Ironman event that you’d have loved to see, but didn’t happen?

I live in Santa Barbara, California, and tried for years and years to figure out how to do a race in our county. It’s a coastal town with a mountain range directly behind, and on the other side is this wine region with a perfect lake. The valley is the perfect place to ride a bike, and there are a bunch of small communities that would make it perfect for the run course. But we’ve never figured out how to make it work because the lake is not cleared for swimming, but an Ironman in Santa Barbara would be awesome, and I could sleep in my own bed.

Finally, will you now be able to take part in another Ironman?

For sure. I wrecked my ACL skiing in March and had reconstructive surgery in April, so this year is out, but the plan is to be active and return. Maybe I’ll do Kona. They might even give me a wildcard [entry] if I play my cards right.