Why (And How) to Run with a Power Meter

(Photo: Hannah DeWitt)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Much like cycling with power, running with power is a way to remove variables from your workout: pesky environmental things like wind and hills that can affect your pace per mile, or physiological things like nutrition, sleep, and cardiac drift that can affect heart rate. Running with power gives you a more absolute number that factors in how steep a hill is (which is good) but also ignores your fatigue levels (which can be bad).

“Precise power targets for training and racing execution can be applied across more varied terrain and wind conditions than other methods of quantifying effort,” said coach Steve Palladino, who uses power extensively with his athletes and as the head coach of the Palladino Power Project. “Further, power facilitates ‘corrections’ of targets for heat/humidity/altitude.”

In other words, much like a cycling power meter, a running power meter helps keep your output numbers objective in the face of everyday external conditions. But it’s not as simple as a cycling power meter, either.

How Does It Work?

Devices meant to measure running power are broken up into two camps—and each use very different methods. First, there are insole-based power meters, which actually measure the force generated with each footstrike via strain gauges. This is more similar to how a cycling power meter works, but it’s important to note that just because both use strain gauges to some extent, they’re still not apples to apples.

Second, and more common, are running power meters that use a footpod or in-watch sensor and a combination of accelerometers, GPS, and barometric altitude—alongside some super-complex math—to make a pretty good guess. Accuracy might take a hit on this method, especially if you’re switching between power meters, but consistency over a longer period of time is good enough.

Both methods require a smartwatch or smartphone to read the data in real time. For his athletes, Palladino prefers the Stryd footpod-based power meter due to its testing. We’ve also had relatively consistent success with on-watch power meters from Coros and Polar.

How Doesn’t It Work?

“Run power can be used very effectively (better than pace or heart rate) in a very broad scope of use cases,” Palladino said. “However, run power may reach technical limits in soft sand, soft snow, very icy/slippery surfaces, severe grades (>20%), and very technical downhill trails.”

It’s also important to note that when an athlete runs, there is a lot more going on with each step—unlike cycling where the exact power you put out is all of the power that makes you move. Your running efficiency (or more accurately: “effectiveness”) also plays a big role in how hard you’re working.

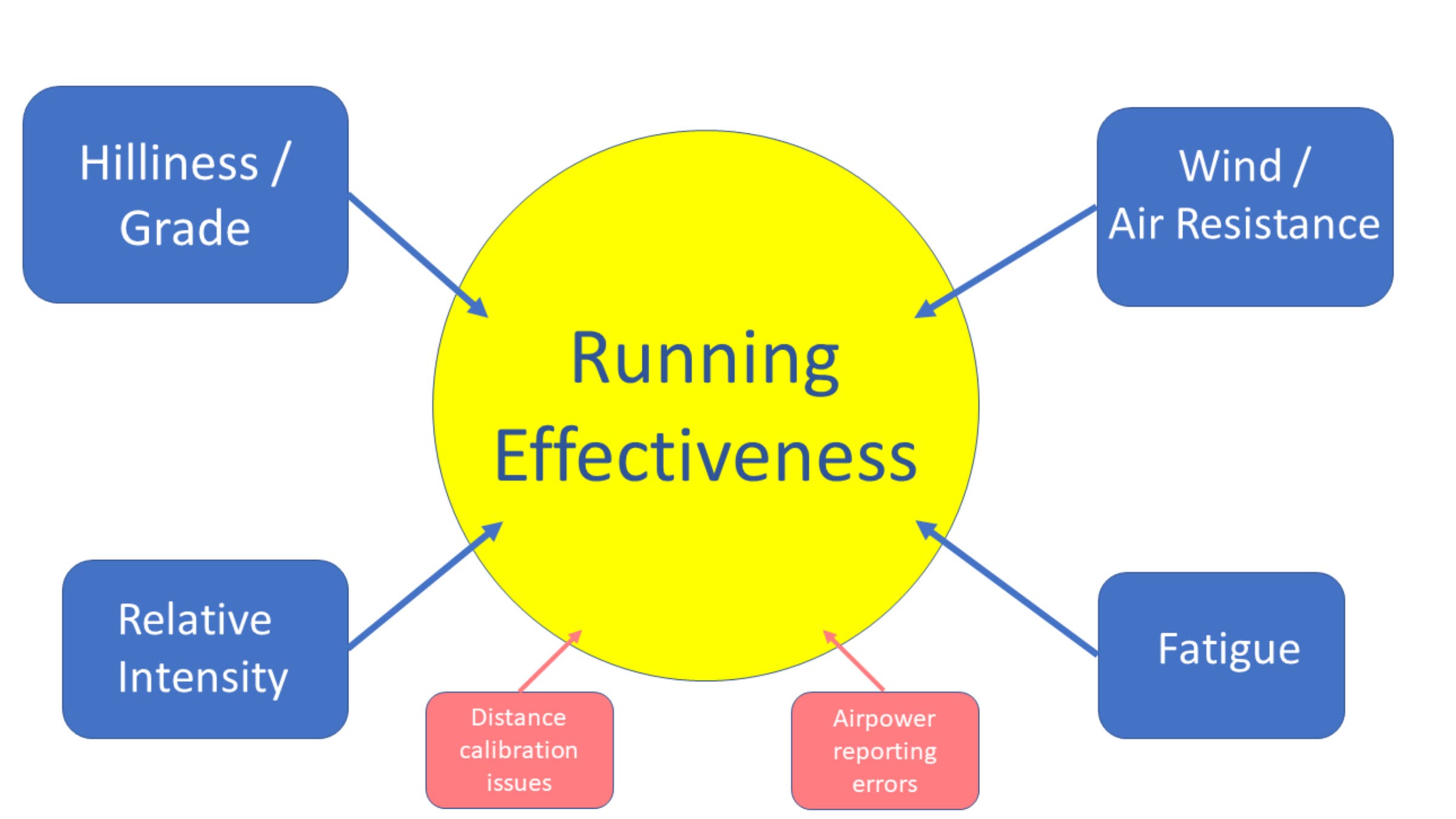

“Running effectiveness is the speed-to-power ratio; how effectively one converts power to speed,” Palladino added. “For example, one’s “running effectiveness” will be higher (better) with a tailwind, than with a headwind: One runs slower into a headwind at the same power than into a tailwind. The relationship is common knowledge, but it can be quantified in running with power—and if quantified, it can be employed to coaching and athlete benefit.”

What Does It Measure?

This is where things get tricky. In cycling, your watts are your watts, and while running power meters output watts, they could just as easily be calling that number “powers” or even “unicorns” as the standard is broadly defined. Furthermore, since so much is going on, biomechanically, you may be putting out a ton of “power” because your form is falling apart (and increasing your heart rate), but that’s not necessarily a good thing. With that in mind, using power as a pacing target is a huge benefit for triathletes who are running off the bike.

“Triathletes might run, for example, the run leg of a half distance triathlon at 85-90% of critical power (CP)/functional threshold power (FTP), while running a half marathon on fresh legs at 94-98% of CP/FTP,” Palladino noted.

“Knowing and learning these variables that determine the differences between a run leg in a triathlon versus a fresh-legged run race for a specific athlete (through prior race successes and failures, and through training) can facilitate a surprisingly precise and effective race plan based on power.”

Aside from setting workout targets and pacing strategies—which remember are slightly variable, based on your running form as it degrades or improves—you can also use running with power to measure your efficiency. Rather than simply using power to determine how hard you’re actually working on a hilly trail—where pace would be nearly useless—you can use power to determine how well you’re running in controlled conditions.

For instance, a runner could try to lower his or her power to hit a certain interval on a flat, measured (ideally windless) course like a track throughout the course of a workout. Or one could try to hit a time trial time the same or faster than earlier in the season with a lower power average over the course of the run. So even though you’d only be a bit faster, when it comes to time/pace, you’d actually be showing efficiency improvement—which is probably the most productive goal a runner could be striving for.

How Do I Start?

The first step is obviously purchasing a running power meter of some kind or investing in a smartwatch with on-wrist running with power included—like Coros’ models or Polar’s upper-end running models. For as little as $200, the Coros Pace 2 is an excellent smartwatch for triathlon (open-water swimming, cycling, and running, along with running power built in).

Next, you’ll need to calculate your critical power (CP)—this is the number that you’ll use to base most of your workouts and pacing strategies off of. While similar in theory to functional threshold power (FTP), critical power in running is not the same as cycling baseline levels. “[It’s a common misconception] that CP/FTP is equal to one-hour power—or that FTP is equal to 95% of 20-minute power,” cautioned Palladino. “Nope. These are rough ways to estimate FTP/CP, but should not be assumed to be equal to CP/FTP.” After you determine your CP values, you can use that number to set training zones and pacing strategies for race day.

If you use a Stryd running pod, it will automatically calculate your CP after a few runs, but it will get more accurate the more often you run—and more importantly as you run with a greater variety of workouts. Stryd also allows you to get a more accurate value by inputting a 5K or 10K time from the last few weeks. For triathletes, they suggest inputting a time off the bike, for the best results. If you want to get the most accurate CP possible, you can also determine your CP value manually via a test that’s similar to a cycling FTP test.

Stryd suggests the following protocol from their website:

15 to 20min warm up with various strides and dynamic drills (we recommend doing 2x30sec @ 3k intensity + 4x15sec @ mile intensity all with 60sec recovery, and dynamic drills of your choosing to prepare for a race effort)

9/3minute test

– 9min time trial

– 30min active recovery (light jogging or walking)

– 3min time trial

– 10 to 15min cooldown of light jogging

6/3 lap test

– 2 laps at a medium effort (record duration)

– 5min easy jog

– 6 Lap Time Trial (record duration)

– 30min active recovery (light jogging or walking)

– 3 lap Time Trial (record Duration)

– 10 to 15min cooldown of light jogging

What Next?

Stryd and other training resources list a bevy of workouts based off of CP—which will be completely different than your HR or pace-based workouts. Also, many coaches like Palladino or Jim Vance (who literally wrote the book on running with power) use running power values in their workout prescriptions and as a way to pace races. One of Palladino’s workout sets is listed below:

– Warm-up

– 2 x [3 miles @ 95-97% of CP/FTP, 0.5 mile @ 105-107% of CP/FTP]

– 3min easy jog recovery between intervals, 4min jog between sets

– Cool-down

When it comes to general race pacing for non elites, Palladino suggests the following, based off CP numbers, and illustrates the difference between running off the bike or running an open, fresh-legged race:

| Run leg in: | % of CP/FTP | Fresh-legged Race | % of CP/FTP |

| Olympic-Distance Tri | 90-95% | 10K | 100-104% |

| Half-Iron Tri | 85-90% | Half Marathon | 94-98% |

| Iron-distance Tri | 75-80% | Marathon | 88-93% |

While it’s not perfect (and not exactly the same as cycling power), running with power can be an excellent way to not only measure your effort in workouts—particularly when on hilly terrain or in windy conditions—but also allow you to benchmark test, increase your running effectiveness, and pace better on race day.