From The Archives: Train The Mark Allen Way

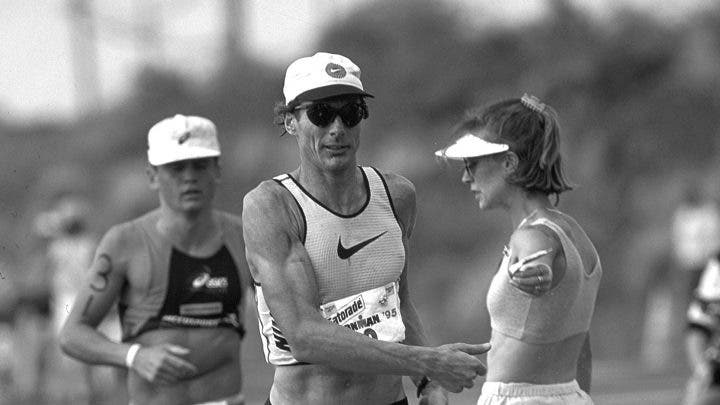

(Photo: Nils Nilsen)

This article originally appeared in the March 2015 issue of Triathlete magazine.

Mark Allen is just like us. If “us” is anyone who’s ever observed the Hawaii Ironman finish line—either in person or on TV—and been instantly beguiled by the prospect of becoming one of those finishers. “Ordinary people were crossing that extraordinary finish line, and I thought, ‘I want to go there and see if I can do that,’” recalled Allen.

He’d never done any formal run training, and his cycling had simply been a practical mode of getting between school and home (he was, however, an All-American swimmer at the University of California, San Diego). Allen embarked on a “six-month crash course on getting ready for Kona,” and started the 1982 world championship but dropped out before the finish. He knew the distance—not to mention the extreme Hawaii conditions—would take some troubleshooting, and Allen spent his first six years in Kona trying to crack the Ironman code before winning his first of six world titles in 1989, the year of his famous “Iron War” with Dave Scott. Today, Allen uses his years of racing experience (not just in Ironman—he also won the Olympic-distance ITU World Championship in ’89) and expansive knowledge to guide other triathletes successfully to the finish line of any triathlon, from Kona to a local sprint.

“I love helping age-groupers because there’s usually just one thing they’re not doing right, and you correct that and their performance just skyrockets,” said Allen.

Allen said there are three “competencies” that contribute to the kind of race day where everything comes together and you’re firing on all cylinders: the physical training, nutrition and mental outlook.

RELATED: Who Ya Got? Triathlon Fantasy Matchup #2

Preparing the Body

Allen believes in training athletes in a way that allows them to approach race day as if it were “just a normal day” of hard training so that anxiety or stress is minimized. Key to this process is taking the body to its limit repeatedly—but methodically—in training so that on race day the body is familiar with the effort and can push through to new levels of performance.

“My whole strategy is helping people reset the gauge of what fast is or what long might be or what steep is so that on race day the response is, ‘Oh, I’ve done this before,’” explained Allen. “Especially for an Ironman, one of the biggest keys is keeping the day feeling as low-stress as possible. You’re able to keep your aerobic metabolism going—you don’t switch over to burning 100 percent carbohydrate because you’re totally stressed out. Once you do that, you run out of gas.”

Depending on the race distance, Allen has his athletes incorporate long training days to get the body used to moving for an appropriate period of time. For Ironman prep, he said there is a three-hour physiological barrier that you have to teach your body to push through in training. “When you hit three hours, you kind of feel rotten for a little bit, and then 15–20 minutes past that you start to come back,” he said. The same happens at around six hours, and you have to train your body to recognize the response and forge though it. For Ironman, Allen said the training plan should include a handful of training days that are going to have you moving for more than six hours. “It can be all on the bike or a combination of swim, bike, run,” he explained. “It’s more just getting your body to move for a certain number of hours.”

Allen also emphasized the value of knowing the race course: What’s the profile? Are there hills or key climbs on the bike? “In training you want to be climbing on hills that are steeper and/or longer than those you’ll encounter in the race so when you’re in the event, your body responds with, ‘This is a climb and it’s hard and long,’ but it knows that you’ve done something steeper and longer so it keeps your perception for how hard it is to a minimum,” he said. The same idea applies to race pace. Allen has his athletes doing speedwork—fartleks on the track and intervals on the bike—for Ironman prep. “I get the question a lot: ‘Why do I need to run quarter-miles at a 5:30-mile pace when in Ironman I’m going to be lucky if I can hold 8-minute mile pace?’ Part of it is physiological—you have to build your aerobic base, and if you use smart speedwork it helps raise your VO2max, and when you do that it raises all of your fitness markers, including your aerobic capacity and fat-burning capacity. And it makes it so when you are in the race and you’re running or cycling at a much slower pace than you did in your intervals, your body knows it’s nowhere near what you know you can do. It’s resetting your gauge of what ‘hard’ is.”

Allen divides the buildup to a goal race into phases. For example, if someone has 12 weeks to get ready for an Ironman, the first third or the first half will be all aerobic work, or base building (depending on the person’s age, as Allen said the older you are, the more benefit you’ll get out of doing more aerobic training as opposed to speedwork). His athlete may do a running race or something occasional, but nothing consistently hard. Then, he’ll introduce speedwork, but cautions against too many anaerobic efforts in a single week. “I see people doing anaerobic stuff five, six times a week—you’ll get fitness gains initially but eventually you’ll start to break down and risk injury,” he warns. “You actually start to erode your aerobic capacity, your capacity to utilize fat for fuel. If you’re doing Ironman, that’s what is going to help you have a great race: if you can utilize fat for fuel. Most people can’t handle more than one anaerobic session per sport per week.”

In addition to hard intervals, Allen said you have to do strength work if you’re going to maximize your results. “The strength work gives you more lean muscle to draw from, and that’s especially important in Ironman because in the marathon when you start to get muscle breakdown and you reach a point where all of a sudden the survival mechanisms in your body start to tell you that you should slow down, that you should quit, if you have put on a little extra lean muscle, in your legs especially, you can push that critical breakdown point to later in the race or you can avoid it completely,” he explained.

According to Allen, strength work for an endurance athlete should be reps that challenge the muscles in new ways and help build a strong foundation (read: not a weight-lifting contest). “I like to build strength in a functional way,” he said. “For example, if you do a squat, you can get the bar on your shoulders and can do a really heavy weight of 12 reps. However, if you do a step-up on a plyometric bench, one leg at a time while you’re carrying weight, you might find that you can’t do it with only 50 pounds on one leg because your platform and your movement isn’t stable. Most triathletes could benefit from developing the core muscles that stabilize their platform, their midsection correctly. Once you have that, you can start to load up the weight.”

When it comes to tapering for a long-distance triathlon, Allen said that the body is best primed for an optimal race-day effort after a strong build with four weeks of gradually cutting back. He said a lot of athletes either shut it down too early so that the body is entering a deep recovery mode too soon, or not giving themselves a sufficient taper window. One specific timing guideline: “Two weeks [of taper] is the worst you can do,” he said, asserting that it doesn’t have your fitness peaking at the right time.

Fueling Right

The toughest part of an Ironman race—or any triathlon? It’s nailing your fueling strategy, said Allen. “The nutrition is still the least developed part of Ironman racing,” he asserted.

Allen holds two major tenets when it comes to race nutrition. The first is that, for most people, the best way to get your fuel is in liquid form. “It’s hard to chew when you’re racing, and it’s even harder for your body to break down something that’s solid,” he said. “If your calories are in a really simple form, your body doesn’t have to do as much work to get it into the bloodstream and working muscles.” And the longer your nutrition is sitting in your gut, the more likely you’ll experience GI distress. “There are some products that I’ve seen recently that seem to have found the right kind of carbohydrate source that gets a bunch of calories in without causing backup or nausea. First Endurance may have finally hit it.”

You not only have to try to keep your calorie tank full (Allen suggests shooting for 300–350 calories an hour), but you should also make sure you’re getting a combo of calorie/carbohydrate sources. Allen emphasizes the widely held sports nutrition belief that absorption of your fuel works best when you consume both quick-burning and slow-burning carbohydrate sources—for example, 300 calories of just glucose won’t be readily utilized as effectively as a combo of glucose and maltodextrin.

Whatever drink or energy source you decide on, Allen stresses the importance of using it consistently in your training, in conditions similar to race day. “If you don’t really care what you take in, find out what’s going to be on the course and train with that,” he advises.

Another essential piece of the nutritional puzzle is electrolyte balance. According to Allen, you can absorb between 30 and 40 ounces of fluid per hour, and the average person needs about 350 milligrams of sodium to be replaced per hour (those numbers will increase in a hot race environment, or in accordance with an extreme sweat rate). He highly recommends having a source of sodium in your race nutrition plan. “If you’re going along and you’re eating and drinking and feeling like your energy is not coming back or you’re having a hard time concentrating, you’re probably getting low on sodium,” he said. “You’ll just start to feel dull. If you’re in that position, take some sodium then and there. Within a minute you’ll start to feel better if that’s what you’re low on. Play with it in training and track what you take in. If you stop at a 7-Eleven on a ride and go straight for the bag of ranch Doritos, you’re craving salt and not getting enough.”

Training Your Brain

Triathletes often put in months of disciplined swim, bike and run training, only to have their race fall apart because they failed to give the psychological challenges of race day much thought. “A lot of the reason you train is to train your mind so that you get good at enduring and sticking with it when you don’t feel your best,” said Allen. “This is something you can practice in every single training session—it’s not something to wait until race day to figure out how to do.”

The ultimate goal is to learn how to quiet the mind so that when you can’t come up with anything positive to think about when things go south (and they inevitably do at some point in the day) you have the mental control to shut off the internal chatter.

“The chatter comes when all of a sudden the outcome you’re trying to achieve feels like it’s way out of reach—completely impossible,” Allen explained. “Things don’t feel worth it, and everything starts to hurt and feel tight and you’re thinking, ‘What am I doing here? I didn’t train right. I don’t feel good.’ Really those are just moments that are begging you to take a breath. When you’re out training and that chatter is going on, take a breath and let it go,” he said. “It’s one very simple technique. And then five minutes later when it starts again you do it again. And you do it again, and again.”

Another important thing to realize, Allen said, is that in the toughest moments of a race, it’s almost impossible to find a positive thought, and even if you do tell yourself something positive, you’re probably not going to believe it. “I find it much more powerful to practice getting into that quiet place where you really don’t have any thought,” he explained. “You’re aware and alert and responding to what’s going on, but you’re not assessing or judging it. Your legs still hurt, you still have blisters, and that person that you thought you should’ve caught is still ahead of you—whatever it is—and there’s way too many miles to go and you don’t think you can make it, but at least you’re engaged in that moment. If you just take it moment by moment, something comes down that gives you a hope or realization that no matter how it turns out, it’s great because of what you just made it through—because that was tough. That’s a success. Then you’re able to really go beyond your ‘ordinary’ and be in that extraordinary space. But you’ll never get to that extraordinary space by trying or by thinking your way to it. Or by pumping yourself up and convincing yourself that it’s worthwhile—it has to come from inside, from that quiet place.”

While many athletes use visualization techniques to get them through rough patches in a race, Allen said that the greatest benefit of the technique can be gleaned pre-race. “It’s good to go through the race in your mind and figure out all the points that could derail you and what your workaround is going to be should those things come up,” he said. “I used to do that. I’d go through the swim and the bike and run and feel a point where there was a resistance or thought of ‘I don’t know what I would do if this happens.’ Tell yourself that no matter what it is, you’re going to deal with it as calmly and steadily as you possibly can.”

In the Mark Allen playbook, another important caveat to a well-rounded mental game is gratitude. When he was racing at the highest level, Allen studied shamanism, and one of the main goals of that tradition is to feel gratitude for your life. “It may sound silly, but just like practicing swimming, biking and running, it’s good to practice having gratitude—to be alive, to even have these types of dreams … to feel gratitude that you have a body that can move, and you can be outside doing these things in nature every day,” he said. “And then when I was in the race it was so much easier, no matter how hard things were, to be grateful that I was out there. I put myself there. Nobody brought me to the start line in handcuffs. This is what I chose to do. Be grateful for it.”