Why Is It So Hard to Pull Off a Good Marathon in an Ironman?

(Photo: Tom Pennington/Getty Images)

Running a marathon in an Ironman is hard. For everyone. But why is it so hard, particularly if you are not a sub-12-hour Ironman athlete?

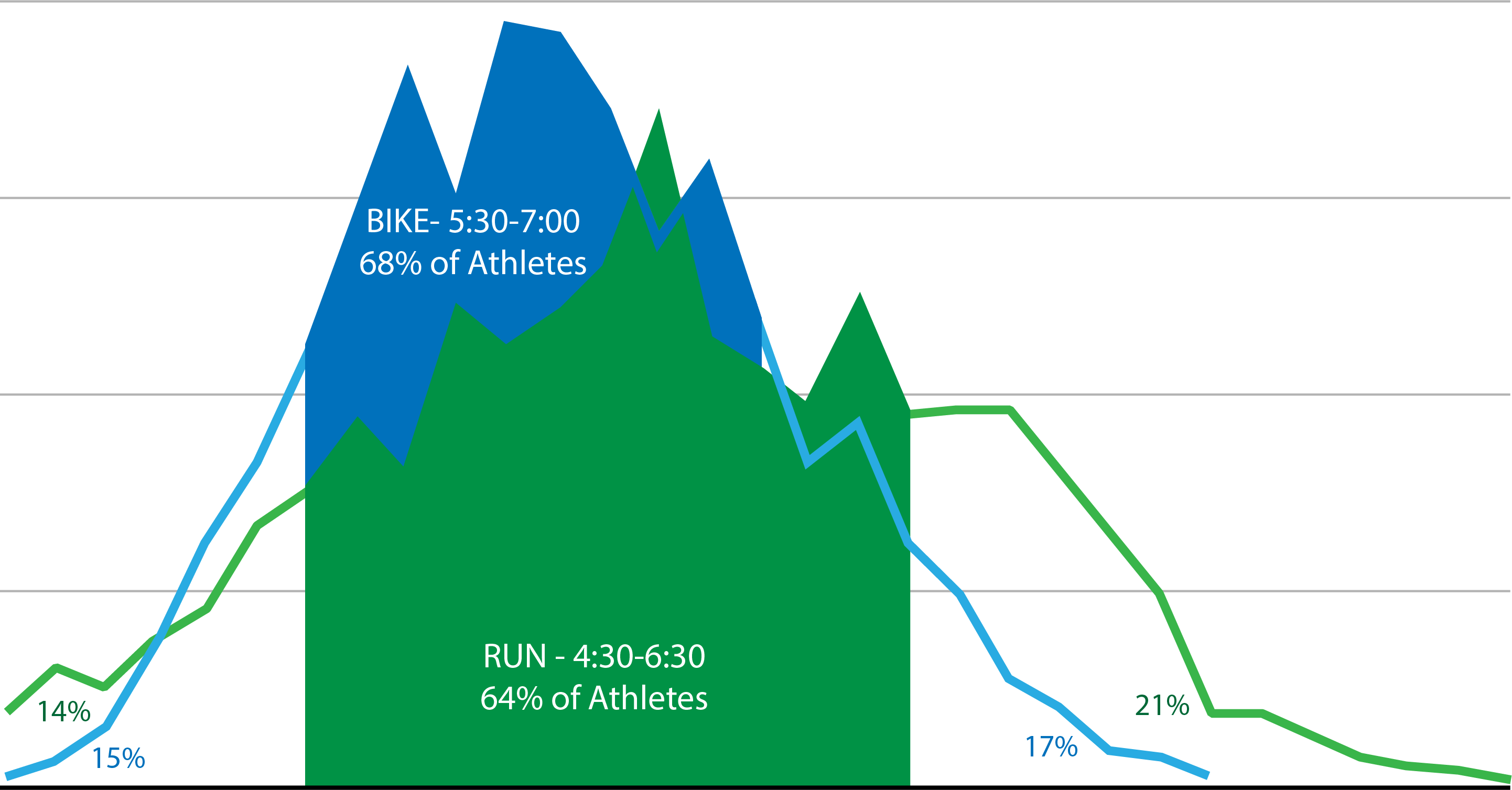

For starters, you’re not imagining things. It is, in fact, more challenging to run a strong marathon if you’re not going to finish in less than about 12 hours. Let’s look at Ironman Maryland 2021: a tame course and a low DNF day (8.8%), or in other words, as good an opportunity as you’ll get for a solid Ironman performance. At that race, about 15% of the athletes broke 5:30 on the bike, and about 14% of the athletes broke 4:30 on the run. Assuming mostly these were the same athletes and these athletes swam sub-1:40 and had reasonable transition times, they finished in less than 12 hours.

So what happened with everyone else? The bike and run splits for the remaining athletes didn’t stay nearly as tied together as the race went on. The bike times followed a normal distribution, with the majority of athletes (about 68%) finishing with bike splits between 5:30 and 7:00, and about the same number of athletes finishing faster and slower than that range. The run times, however, painted a different picture. While the majority of athletes (about 64%) finished with run splits between 4:30 and 6:30, roughly 1.5 times as many athletes finished slower versus faster than that range.

While we’d need athlete-level data to conclusively correlate bike and run splits, it’s clear from the aggregate data that: (1) there is both a wider range of run splits than bike splits, and (2) the run split distribution leans toward slower times whereas the bike splits are evenly distributed. It’s reasonable to conclude then, that the longer an athlete is on the bike, the greater the chance of their run split slowing relative to their bike split. And the splits that define the breaking point for this deviation (with some assumptions about swim times) add up to right around the 12-hour mark.

Running a marathon in an Ironman IS hard

So now that you can say with assurance that “it’s not just me,” let’s dive into why a strong Ironman marathon can be so elusive if you’re not a sub-12-hour finisher. The challenges stem from an athlete’s overall training volume relative to time on the race course, the cumulative effect of training stress on race day, and the limitations of the human gastrointestinal system.

There are only so many hours in a week

Most athletes preparing for an Ironman-distance event will build to 14-18 hours of weekly training during their final few training cycles, regardless of expected time on the race course. These upper-end limits are typically dictated both by time available for training as well as the training volume that our bodies can tolerate, so there’s not a lot of room to change them. But 14-18 hours of weekly training for an 11- to 12-hour Ironman finisher provides a greater weekly-training-volume-to-race-time ratio than it does for a 14- to 16-hour Ironman finisher.

When we translate time to distance, the difference in ratios becomes even more dramatic. An 11- to 12-hour Ironman finisher is going to cover more miles per hour of training than a 14- to 16-hour Ironman finisher. So the weekly-training-miles-to-race-miles ratio for an 11- to 12-hour Ironman finisher is substantially greater than that of a 14- to 16-hour Ironman finisher.

Those athletes who are able to complete an Ironman well within the upper ranges of their weekly training volume and mileage have a good amount of fitness left in their legs when it comes time to run the marathon. But those whose finish times push up against or even exceed the upper end of their weekly training volume and mileage are asking a lot of their fitness when it comes time to run.

RELATED: How Many Training Hours Does It (Really) Take to Conquer Ironman?

Fatigue is cumulative

There’s no detailed explanation needed to understand that the longer an athlete has been exercising before they start the marathon, the more fatigued their body will be. We can dive deeper into the measure of training stress, though, to understand how effort level and duration for the bike leg contribute to total training stress for that discipline, how to optimize that balance, and the challenge of achieving that if an athlete’s bike split is over six hours.

There is a theory that an athlete’s bike leg in an Ironman should have a Training Stress Score (TSS) of no greater than 300, and closer to 275 for most well-trained age group athletes, in order to run well off the bike. Setting aside issues with the details of TSS calculation, the overall concept of balancing effort and duration to achieve optimal training stress on the bike leg is a reasonable one. More importantly, the theory has borne out in practice for most athletes.

Going by this principle, then, if an athlete completes the bike leg in six hours at a typical Ironman effort level (65-70% of FTP, or upper-middle Zone 2), they will generate a TSS of about 275-300 for the bike leg and will have optimized their training stress. If an athlete’s bike speed at that effort translates to a sub-6-hour bike split, they actually have room to increase their effort level and still maintain a sub-300 TSS for the bike, which further decreases their bike split. In contrast, if an athlete’s bike speed at that effort translates to a 6-plus-hour bike split, they will need to decrease their effort level in order to limit their training stress on the bike to 300.

And there’s the crux of the problem: decreased effort level may help optimize training stress, but it also slows bike speed and increases the duration of the athlete’s bike leg. For some athletes, there’s simply no math where effort level and speed result in both optimal training stress and a bike split that meets Ironman cutoff times. For athletes who can make this math work, they then must weigh the benefits of optimizing bike training stress against the challenges of starting the marathon deeper into their day (see both above and below).

RELATED: Race (Don’t Survive) The Run

Fueling the body is a losing battle

In order for an athlete to take advantage of their fitness on race day, their body needs to have resources: fuel, fluid, and electrolytes. As they swim, bike, and run on race day, they move through those resources and must continually replenish them – which is easier said than done. The limits of the body’s gastrointestinal system make it impossible to replace fuel (calories, largely in the form of carbohydrates) at the rate it is consumed. Because of this, all athletes dig themselves into caloric deficit at a rate of several hundred calories each hour. It’s unavoidable.

An athlete can, however, replace their fluids (water) and electrolytes (mostly sodium) at the rate that their body moves through them, i.e., at the rate that they sweat them out. Assuming that an athlete knows their sweat rate and sweat sodium concentration and that they are focused on rehydration (which are all big assumptions), they can replace fluids and electrolytes on a one-for-one basis the entire time they’re on the course.

For most athletes though, it’s challenging to perfectly rehydrate while they’re on the bike. And given that it’s impossible to perfectly refuel due to the limits of our GI system, all athletes will start the run with bodies that are under-resourced. The more hours that elapse on race day before an athlete starts the run, the more dramatically their body is under-resourced, and the harder it is to run well.

RELATED: How to Get Through an Ironman Without Sh*tting Yourself

Running a good marathon in an Ironman is hard – but not impossible

Running a marathon in an Ironman is hard. And the longer an athlete is on the course, the harder it becomes. So should you throw in the towel and resolve yourself to a long walk? Absolutely not. Hard is not impossible. Hard just means you must focus diligently on the factors contributing to your success.

Don’t shortchange your training volume

Yes, things will come up on occasion and you will miss a workout. That’s okay – we’re not looking for perfection. You do, however, want to maximize your weekly-training-hours/miles-to-race-day-hours/miles ratio as best you can, so any time you are teetering on the edge of do-I-or-don’t-I-do-the-workout, the answer is: do the workout. (Injury- or illness-related reasons excepted, of course.)

Pay close attention to bike pacing on race day

Set your effort-level targets ahead of time with the goal of properly balancing effort and duration for your bike leg. If in doubt, err on the side of biking a tad easier, as saving 10 minutes on the bike can often cost you 30 on the run.

Fuel and hydrate like your race depends on it (because it does)

That starts the week prior to race day, so that you show up at the start line with your fuel, fluid, and electrolyte resource tanks full and balanced. During the race, have a fueling and hydration plan that you’ve proven through practice in training, and have systems in place to make sure you stay on plan (for example, alarms on your watch and/or bike computer can remind you to eat/drink).

Realistically define what a “strong” marathon looks like for race day

Set your goal marathon pace based on your current overall fitness and run paces, acknowledging that your goal pace may in fact be slower than your training pace. Adjust that pace mid-race as needed based on your fatigue coming off the bike and your fueling and hydration status. Don’t be afraid to incorporate planned walk intervals into your run – they don’t detract from an overall strong marathon, and often aid in your ability to stay strong the final 10 miles.

And above all, be willing to dig deep. Really, really deep. Oh – and remember to drink the Coca-Cola at the aid stations. You’ll know when it’s time.

RELATED: Triathlete’s Complete Guide on How to Train for an Ironman

Alison Freeman is a co-founder of NYX Endurance, a female-owned coaching group based in Boulder, Colorado, and San Diego, California. She is also a USAT Level II-certified and Ironman University-certified coach as well as a multiple iron-distance finisher.