New perk! Get after it with local recommendations just for you. Discover nearby events, routes out your door, and hidden gems when you sign up for the Local Running Drop.

Everyone’s different, but my case of atrial fibrillation (AF) is instructive about what athletes may face. It happened to me at age 48. I was training hard for the upcoming summer bike race season. My team and I were putting in long training miles, race efforts, and threshold work. We were racing on the weekends and training during the week.

Then I broke my ribs in a crash. If you have ever broken a rib, you know how much the injury slows you down. Breathing hurts, sleeping hurts, and sneezing is like an electrical shock coursing through your body.

But there was a third component that led to my AF. On top of an intense training load and a rib injury, I was also working full-time as an electrophysiologist. It’s fascinating work, but it’s also exhausting; among other things, it involves standing in the laboratory draped in a heavy lead apron for hours at a time, walking repeatedly down the long halls of the hospital, and continuing to make patient rounds. Being a cardiologist is demanding in itself, but with a rib injury and fatigue, it was fertile ground for the development of AF.

One hot summer day after the crash, I was on a training ride with my teammates. That day I had taken no pain meds, and my ribs hurt a lot on the ride. But I was doing okay. I was rotating in the line, taking my turns. Then it happened. We were 40 kilometers from home when I noticed an abrupt onset of breathlessness and an utter loss of power. It was more than the heat; it was something else. My heart rate monitor showed funny numbers. The beats were irregular, and any slight rise in the pavement caused my heart rate to spike much higher than normal.

I had to let the ride go on without me. Moments before, I was pulling through easily. But now I couldn’t hang with the group. A friend stayed with me, pushing me up hills. When I finally got home, I told my wife that I thought I was in AF. She is a hospice and palliative care doctor, so for her, AF is hardly alarming. She felt my pulse and seconded my suspicion. “You have an irregularly irregular pulse,” she said. “Yep, you have AF.”

Since I am a cardiologist, I decided to confirm the diagnosis myself. I showered and dressed and went to my office to do an ECG, an echocardiogram, and some simple blood tests to check my thyroid function. The tests showed that my heart was fine, other than the rhythm being in AF. That night, I went home and rested. My partner in our practice called in some medication for me. I swallowed the pills and went to bed preparing myself mentally for a day of tolerating the fibrillation and irregular pulse. I figured I’d do a full day of work and then get cardioversion (shock) afterward.

The next morning, I woke up without the butterfly sensations in my chest. My pulse was regular. I was back in sinus rhythm, and I felt a small hope that I was in the clear.

I took Flecainide (a drug to stabilize heart rhythm) for a few months, a regimen I prescribe for my patients. My heart improved, but it wasn’t exactly smooth sailing. Over the next year or so, I experienced frequent skips, jumps, and flutters (doctors label them “palpitations”) of the heart rhythm. I could feel them in my chest and throat. They occurred at rest and when I rode. On two other occasions in the following months, I had a few hours of AF episodes.

In retrospect, I should have seen the signs. I was injured, I was training excessively in the heat of summer, and I was still trying to work full-time. What I should have been looking for was balance; it should have been obvious I was asking too much of my body. Instead, I kept pushing myself to continue my routine—my “normal.” But of course I was anything but normal by then.

RELATED: Understanding the Effects of Exercise on Your Heart

Warning Symptoms

If my case has any instructive use, it should be to demonstrate that there are plenty of warning signs of trouble. The key is to heed them. But what are they? And what should you be looking for in yourself?

There are two types of symptoms to worry about. Both fall into the category of “not normal.” Your immediate sensations are a good guide. You have probably been training for many years, if not most of your life. Those years of training have given you a good sense of what “normal” feels like. What you are looking for is anything that falls outside the boundaries of normal. For example, a brief flutter in your chest on a ride is probably nothing; nearly everyone gets one from time to time. A flutter that won’t go away, however, is cause for concern. A sustained irregular heartbeat is an abnormal feeling that should set off an alarm.

Sensations that are not normal include

- Racing heart: Any sustained racing of the heart that won’t go away.

- Chest pressure or pain: Especially pressure or pain that worsens during exertion.

- Labored breathing: Difficult breathing that is out of proportion to effort (everyone breathes hard when climbing hills or sprinting).

- Fainting or near-fainting: Anything more serious than the everyday lightheadedness you might feel after a hard effort.

These symptoms are serious warning signs that should alert you to possible trouble. Sustained chest pressure or chest pain warrants a call to 9-1-1. All others warrant an appointment with your doctor, sooner rather than later. If you experience these symptoms, you should stop training until you can be evaluated by a professional.

Secondary warning signs include sensations that are not normal but usually less worrisome, including

- Palpitations: Skips, jumps, or flutters of the heart rhythm.

- Consistently low power: A decrease in sustainable power is the real warning sign here. There are lots of reasons for low power output, including natural variability, overtraining, and medical conditions. Usually it’s the first two. But if your sustainable power drops, take note.

- Excess fatigue: Like low power, generalized fatigue can be caused by many factors. In fact, fatigue may be one of medicine’s most nonspecific symptoms. Causes range from poor sleep or overtraining to a host of specific medical conditions.

- Excess irritability: Irritability is often a sign of overtraining or inadequate nutrition, but patients with arrhythmia or other medical conditions often say they are irritable. Spouses sometimes notice this symptom first.

When Should You See a Doctor?

Sustained racing of the heart, chest pain, difficulty breathing, or fainting are symptoms that mandate a formal evaluation by a doctor. The four less specific symptoms mentioned above—palpitations, low power, excess fatigue, excess irritability—may warrant a doctor’s visit, too. But those symptoms are less worrisome.

Before you see a doctor, try some simple things first. Skips of the heart rhythm, low power, fatigue, and irritability often improve with rest and nutrition. Although many athletes find any period without exercise challenging, either a short period of rest or an even longer period of prolonged rest may resolve the symptoms.

Another thing an athlete with the less worrisome symptoms can do before going to the doctor is to pay close attention to nutrition. This means not only eating enough healthy food, but also abstaining from the following irritants to the heart.

Alcohol

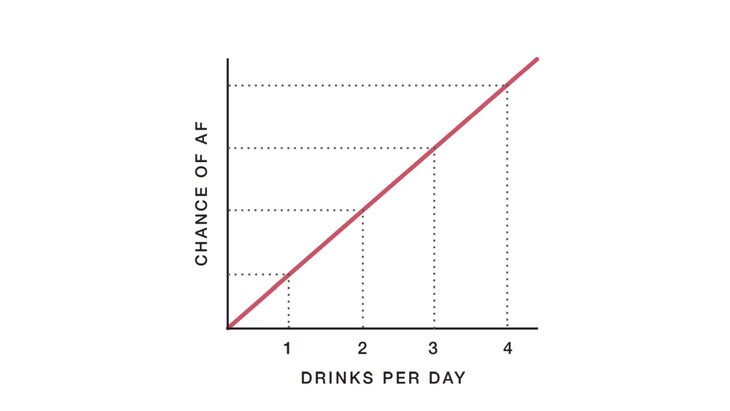

By far, the number one (legal) irritant to the heart is alcohol. The relationship of alcohol to heart rhythm is well known. The French paradox suggests that one or two drinks per day may lower the risk of heart disease, but the relationship of alcohol to arrhythmia is linear, as shown below. One drink per day leads to a small risk of AF; two drinks double the risk; three drinks triple the risk; and so on. Numerous studies have confirmed that reducing alcohol intake may reduce the burden of arrhythmia.

Stress

Excess stress, whether mental (trying to juggle an overbooked calendar) or emotional (divorce or the death of a loved one), can associate with heart rhythm problems. Yet it is impossible to be alive and not experience stress. The issue is not avoidance of stress, but how well you manage it.

I’ve helped hundreds of patients through arrhythmia flare-ups caused in large part by major life events. Quite often, there is little that you can do to avoid these things. What you can keep in mind, however, is the knowledge that the stress will pass, and so may the burst of arrhythmia. If you are experiencing some of the less worrisome symptoms of trouble mentioned above, one option you have before seeing the doctor is to let some time pass until you clear the immediate cause of stress.

However, chest pain, breathlessness, sustained racing of the heart, or fainting should not be passed off as stress. These more severe symptoms warrant attention.

Caffeine

Oddly enough, caffeine’s relationship to rhythm problems is unclear. Old thinking had it that caffeine could cause or exacerbate rhythm problems. New data, including multiple large observational studies, suggest that caffeine does not associate with arrhythmias. In fact, the most provocative finding indicates that the favorite pick-me-up of so many athletes may actually confer a lower risk of arrhythmia. That’s not a misprint. It may sound strange, but it’s what the science shows. Here are a few of the largest studies on caffeine and heart disease:

Caffeine and premature beats. In the largest study to evaluate the association of dietary patterns and heart rhythm problems, a group of US researchers published a report from the Cardiovascular Health Study, a longitudinal study sponsored by the National Institutes of Health of more than 5,000 older adults recruited from four academic medical centers. A longitudinal study means people sign up to have their health followed over long periods of time. (The most famous of these types of studies is the Framingham Heart Study) The research group found no relationship between caffeine consumption and the numbers of premature beats from the atria (PACs) or ventricles (PVCs). This non-relationship persisted after adjustment of possible confounding factors.

Caffeine and AF. The evidence that caffeine does not associate with AF is even stronger. In 2013, a research team from Portugal culled together seven studies that included more than 115,000 individuals. They found that caffeine exposure was not associated with an increased risk of AF. What’s more, when only the highest-quality studies were considered, the researchers found a 15 percent reduction in AF with low-dose caffeine exposure. A larger study from a group of Chinese researchers confirmed these findings, including the same sign of AF protection with low-dose caffeine exposure.

Caffeine and electrical properties of the heart. Caffeine exposure has been tested in a randomized clinical trial in patients with known arrhythmia. Canadian researchers studied 80 patients who were to have catheter ablation of supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). One hour before the procedure, half the group received caffeine tablets, and the other half received a placebo. Although caffeine increased blood pressure, it did not have any effects on the measured electrical properties of the heart.

Caffeine and general cardiac health. The largest study on caffeine and heart disease included more than 1.2 million participants. In this case, researchers reviewed 36 studies from the literature and found that moderate coffee consumption (3 to 5 cups per day) associated with a lower risk for heart attack, stroke, or death related to heart disease. Yes, lower.

An important caveat is that most of these studies look at populations, not individuals. That means that although certain people may not be sensitive to caffeine, others—perhaps, you—could be quite sensitive to it.

We know this information sounds counterintuitive. We’ve heard from many athletes who feel less arrhythmia after reducing or eliminating caffeine intake. The confusing thing about heart rhythm problems is that it’s hard to sort out what caused the reduction in symptoms. Heart arrhythmias have natural variability, so it might be mere circumstance. Another possibility is that when people get a diagnosis of a heart problem, they adjust things besides caffeine consumption, such as the amount of training they do or sleep they get, or what they eat. Doctors call these things confounding factors.

The caffeine revelation has caused a significant reversal in thinking. Doctors ask patients with arrhythmia to give up a lot: alcohol, training, stressful situations, and more. It’s nice that athletes can enjoy an espresso without guilt.

Adapted from The Haywire Heart by Chris Case, Dr. John Mandrola, and Lennard Zinn, with permission of VeloPress.

https://www.velopress.com/books/the-haywire-heart/