Study: Better Gut Germs Might Mean A Faster Ironman

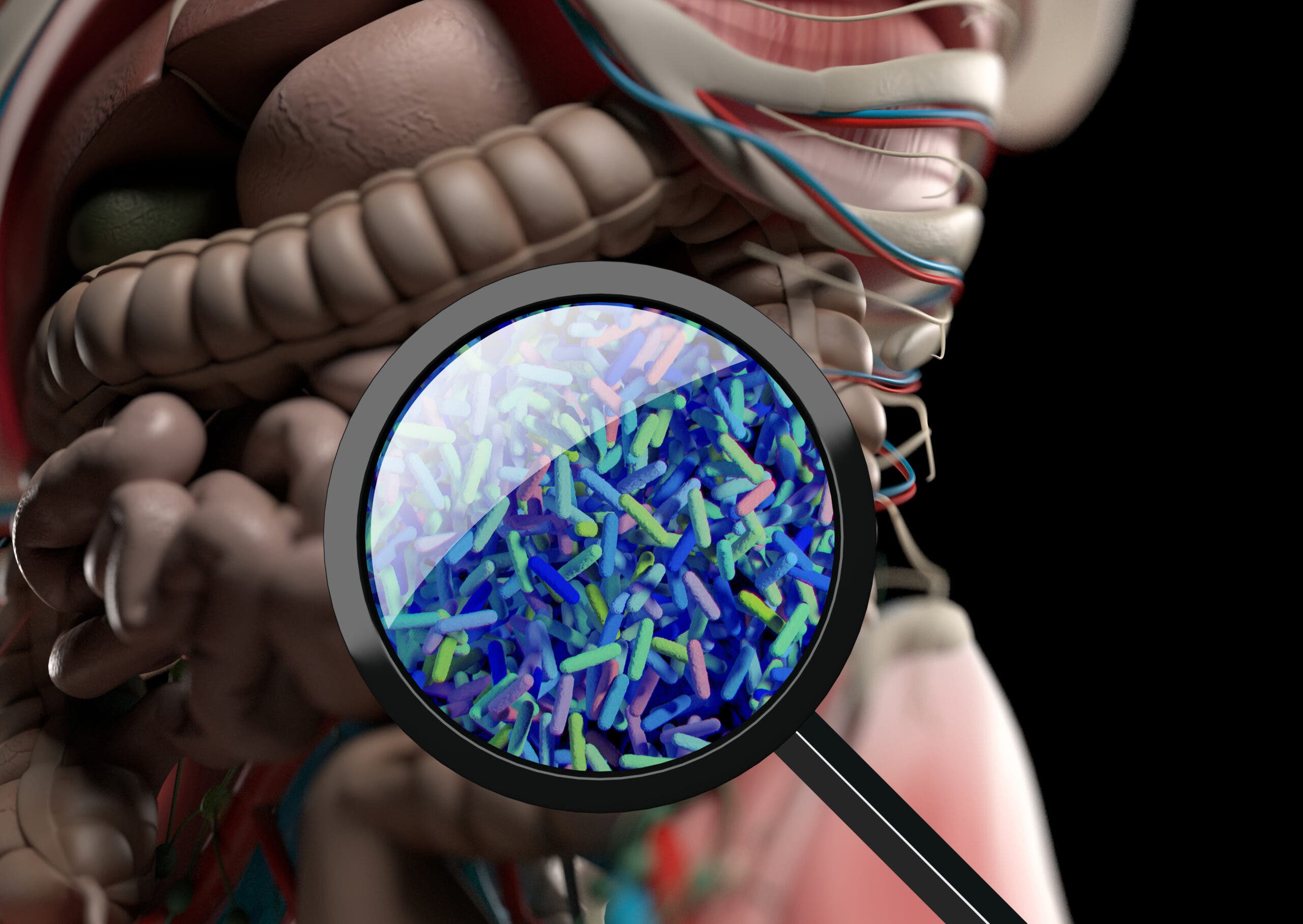

A new study has found athletes with certain bacteria in their microbiome record faster Ironman triathlon times. (Photo: Jasmin Walter/Getty Images)

If you’ve ever done an Ironman, you know just how wrecked the body can feel for in the days and weeks following. Whether it’s sore muscles, dehydration, or a deep fatigue, every athlete who was out on the course will most definitely feel the effects of such an intense effort. If you’re curious about all of these effects, this is an excellent article: A Physiological Look at What Your Body Goes Through in an Ironman.

Though you may be feeling it in your muscles and probably even your brain, there’s another part of your body that is deeply affected: your microbiome. A new study shows the oft-misunderstood bacteria in your body may work just as hard as your muscles when it comes to powering through 140.6 miles.

Understanding the microbiome

Our digestive tract, starting at the mouth and ending at the anus, is more or less a tube. The food we eat passes through this tube, where the intestines digest it into its component parts and absorb the nutrients to allow us to live. Microorganisms also gain entrance into the gastrointestinal tract in this way, and many take up residence there. Far from being unwanted, these microorganisms are an important contributor to our continued existence.

This extensive community of bacteria (and to a lesser extent, of fungi and viruses) constitutes what is called the “microbiome.” The bacteria of the microbiome synthesize essential vitamins and help us digest many of the foods that we eat. A healthy microbiome is known to positively influence inflammation, immune function, and even mental health while a less healthy microbiome can be associated with disease and morbidity from a variety of non-gastrointestinal causes.

The microbiome is principally determined by diet. Those who consume a balanced diet high in grains and vegetables tend to have healthier more diverse microbiomes while those who consume high-fat diets will have microbiomes with less diversity, populated by organisms that can promote disease. The microbiome can be augmented by consuming foods rich in probiotics. This includes yogurt, cottage cheese and kombucha and fermented foods like pickles or kimchi.

The microbiome’s role in athletic performance

Over the past several years, researchers have also gained an appreciation for the importance of the microbiome in facilitating athletic performance. Studies have shown that elite athletes across several different kinds of sports have drastically different microbiomes than age matched sedentary controls. For a long time, it was thought that these differences were simply a result of the distinctive diets that athletes and sedentary individuals avail themselves of but more recent studies have shown that in fact, exercise itself also plays a role in what organisms makeup the microbiome of athletes.

There are a couple of reasons for this. First, the bacteria of the microbiome facilitate the breakdown and digestion of long chain polysaccharides. Athletes require specific types of bacteria in their gut to be able to use these forms of medium- and long-term energy sources and exercising over time promotes an environment in the gut that is welcoming to these species. Second, the microbiome alters function in the muscle cells improving metabolism and performance, though precisely how this happens is unclear.

A recent study in the Journal of Physiology went a long way to demonstrating how important the microbiome is for exercise performance. Researchers divided mice into three groups; exercise, sedentary and exercise while taking antibiotics (these drugs destroy the microbiome) and then evaluated their ability to perform a physical exertion test to exhaustion. The mice who exercised were unsurprisingly better able to perform than the sedentary mice. Interestingly, the exercising mice also performed significantly better than the mice who exercised while taking antibiotics. When evaluating the microbiomes of the three groups, the exercising mice had more diverse and plentiful microbiomes than the sedentary mice who in turn had significantly healthier microbiomes than the mice who had taken antibiotics.

Perhaps most fascinating of all, when samples of the microbiomes of the exercising mice were then transplanted to the mice who had been given antibiotics, their performance in the exertion test increased to the same level of the mice in the first group. This showed how important the microbiome was to exercise performance. The authors theorized that this was not only because the new healthier microbiome allowed for improved digestion and absorption of carbohydrate fuels for endurance but also because of the upregulation in specific genetic expressions in the tissues seen in mice with healthier microbiomes suggesting that the microbiome “may affect endurance exercise capacity by augmenting skeletal muscle metabolic function.”

How Ironman affects the microbiome

Another recently-released research article is of particular interest to multisport athletes. Published in June of this year in the Journal of Applied Physiology, this study looked at the microbiomes of 12 triathletes participating in the 2021 Ironman Indiana, and evaluated whether the makeup of the microbiome was different in athletes with different training histories and was associated with finishing times. In addition, the researchers hypothesized that the stress of participating in such an ultra-endurance event would result in an acute change in the microbiome.

What they found was intriguing (though after learning of the first study referenced here, likely no longer surprising). First and foremost, those participants who had the longest history of training leading into the event also had the highest concentrations of specific bacteria in their microbiomes associated with carbohydrate metabolism. These species are known to also be protective against many types of disease states, making these microbiomes healthier. Athletes with the highest concentrations of these bacteria (A. muciniphila and M. smithii) also had the fastest finishing times.

Even the slower athletes in this cohort still had higher than expected levels of M. smithii, a bacteria that is commonly seen in greater abundance in professional vs amateur cyclists. The authors suggest that this species is likely selected for because of the training done for an Ironman.

While the authors did not find that the microbiome changed in any way over the course of the event, they did determine that how the bacteria metabolized fuels did, suggesting that the community function of the microbiome shifted in measurable ways though why this occurred and what impact this had remained unclear.

From all this research we can make some pretty broad and important conclusions:

- The health of our microbiome is dependent on a balanced and healthy diet.

- The makeup of the microbiome is affected by physical activity and in turn positively affects exercise performance.

- Anything that negatively impacts the microbiome, such as a high-fat diet, being sedentary, or taking antibiotics, can have a negative impact on athletic performance.

All of this serves as an important reminder yet again of how much we need to pay attention to what we put in to our bodies. Sometimes, there are things that we might not think of as being important that can have an outsized role in how we perform. Your microbiome is most certainly one of those things.

READ MORE: Everything You Ever Wanted To Know About The Microbiome (But Were Afraid To Ask)