New perk! Get after it with local recommendations just for you. Discover nearby events, routes out your door, and hidden gems when you sign up for the Local Running Drop.

The below excerpt was adapted from the new book Training and Competing with a Continuous Glucose Monitor by Hunter Allen.

ALL OVER THE WORLD, PEOPLE ARE MEASURING their glucose levels to better understand how to stay healthy, how to improve performance, and how to make positive behavioral changes. And we’re not just talking about those with diabetes – any athlete can benefit from having an understanding of their glucose levels.

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) have been in use since the early 2000s, but their accuracy was so good that in 2016, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved CGM readings to replace finger-stick measuring. People with type 1 and type 2 diabetes have been using CGMs since that time to better understand how much insulin to use, what the impact of foods are on their glucose, and how to change their diet to control their glucose levels throughout the day and night.

Since 2022, athletes have had access to CGMs and their glucose data. Up to that point, scientists, researchers, and doctors around the world really didn’t know what non-diabetes users’ glucose levels might be, how they reacted to certain foods, and what happened to their glucose levels during exercise, sleep, and throughout all aspects of life. Researchers only understood glucose responses from their studies on people with type 1 and 2 diabetes, so it has been with some shock, surprise, and excitement that they’re learning about the responses in people without diabetes, including athletes.

Any athlete or active person can improve their performance by learning about, understanding, and making changes to their behavior just by using a CGM to track their glucose levels. It’s an incredibly exciting and effective wearable that gives the user more insight into their body on a continuous basis, allowing them to make better fueling decisions in training, competition, and in daily life.

Learning your glucose level is going to be more than just an interesting number: It’s going to help you to make decisions at every meal, every workout, and every competition. It truly will become, for you, an optimal performance tool.

Why should you care about your glucose?

Improve your fueling for better athletic performance

If your glucose levels are low or they drop below a certain threshold during exercise, then you’ll be unable to perform at your best or possibly at all. Low blood sugar (glucose), or hypoglycemia, makes training and/or competing nearly impossible. Hypoglycemia, or “bonking” as triathletes call it, usually occurs when your glucose level falls below 70 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL). This can give you shakiness, dizziness, headache, muscle weakness, confusion, and, of course, hunger. When you exercise, your liver releases stored glucose (called glycogen) into your bloodstream so your cells can make energy. At the same time, you ingest additional carbohydrates from food, which replaces the glucose used during exercise and helps to maintain glucose levels so that you can use these easily, and preserve stored glycogen. These two combinations allow you to perform at a high level of intensity and for a much longer time.

If your glucose is constantly dropping and you’re not ingesting more carbohydrates, you will only be able to exercise for so long. Your muscles contain enough glycogen for 60 to 120 minutes of intense exercise, and your liver contains about 30 minutes of stored glycogen for a total combined possible amount of 2.5 hours of stored glycogen. For optimal performance in events longer than two hours, you’ll want to eat carbohydrates before these glycogen supplies are depleted. By eating the correct type of carbohydrates at the right time, you can carefully regulate your glucose to maintain an optimal level before, during, and after your workouts and/or competitions. Recognizing during your exercise the different scenarios that your glucose levels might undergo helps you decide whether you need to ingest a quick-acting or a slower-acting carbohydrate. Your CGM will also help you track your recovery. It will give you insights on optimal foods to consume after the workout or before bedtime in order to improve recovery.

Establish your baseline glucose and your glucose performance zone

For the first two weeks with a CGM, your focus should be on gathering and observing the data. Resist the temptation to change your diet. Make sure to make “ranges” around your meals (including before, during, and after eating until your glucose comes back down again), exercise, sleep, and stressful situations. This will allow you to see your peak glucose value, how fast it gets to its maximum, your average for that specific time, and how long it takes for your glucose to come back down. This will also allow you to establish your baseline (basal) glucose value. What is your norm? Generally, during the day, does your glucose hang around 90 mg/dL? 100 mg/dL? This could be considered your daily “pre-meal or pre-exercise” baseline. Theoretically, your true “baseline” is measured only in the morning after an overnight fast. Both of these – your daily baseline and your true morning baseline – could change over the course of the next six months, so write it down to reference later.

Maintain more stable energy throughout your workout and day

When your blood glucose levels drop, you begin to feel lethargic, sleepy, and you might even find yourself in a bad mood. When you’re on a roller coaster of high glucose then low glucose, it’s hard to perform well throughout your workout, and it’s tough on your liver, pancreas, and even your brain as you try to focus and concentrate. High blood glucose is not as big of a problem if you’re staying below 200 mg/dL, which is around the top limit for normal healthy athletes that don’t have type 1 or 2 diabetes. However, high glucose is not something you’re striving for. More is not better in this case, as high blood glucose levels can cause inflammation, damage to the internal walls of your arteries and vessels, and puts a strain on your pancreas to secrete more and more insulin to stabilize your body back to its basal level.

A relatively stable glucose will allow you to perform at a high level, be focused throughout your workout and/or competition, and will ultimately help you to focus on your training and racing.

Be accountable to your diet

Like any measuring tool, whether that is a heart rate monitor, stopwatch, or step counter, once you become aware of something and you can measure that thing, you’ll improve it. Take that measuring tool away and you lose the ability to know what exactly is happening and, in this case, what is happening inside your body and how it reacts to ingested foods. I know that when I am using my CGM, I still make different food choices even after having used one now for over two years. I know that eating tortilla chips will absolutely blow up my blood glucose to over 200 mg/dL every time I have some, but if I don’t have a CGM on, I’ll reach for that bag of chips! The accountability factor of using a CGM is a real thing, and it can keep you on track.

Improve your metabolic health

What is metabolic health? Great question! There is no universally agreed-upon definition of metabolic health, but some scientists and doctors define it as the absence of metabolic concerns. Low abdominal fat, low triglycerides (less than 150 mg/dL ), low-fasting blood glucose (less than 100 mg/dL ), low blood pressure (less than 130/85 millimeters of mercury (mmHg)), and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (40 mg/dL or less in men and 50 mg/dL or less in women) are all indicators of good metabolic health. Improving your metabolism, which is the conversion of foods to energy in your body, can directly impact your ability to perform at any level in athletics. If you can more efficiently convert foods into the substrates your body needs to perform well, then you’ll be able to perform at an increasingly higher level in your chosen sport. The great news is that all the training you currently do also improves your metabolic health, including making you more sensitive to insulin, reducing the risks of disease, type 2 diabetes, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. At the same time, training also helps to improve your numbers in the five indicators of good metabolic health listed above. So, it’s an upward spiral of improvement. Exercise more, improve your metabolism and metabolic health, wear a CGM, understand how your glucose level responds, and make better choices to further improve your glucose stability and therefore metabolic health.

Reduce your risk of type 2 diabetes

Yes, athletes can get type 2 diabetes! In the book, The Great Cholesterol Myth, authors Dr. Jonny Bowden and Dr. Stephen Sinatra wrote, “Insulin resistance is the root cause of heart disease and insulin resistance is essentially an error of metabolism.”

And Dr. Robert Lustig, the author of Metabolical, said, “Emerging evidence shows that insulin resistance is the most important predictor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.”

Measuring your glucose value on a minute-by-minute basis throughout the day with a CGM makes you acutely aware of every increase or decrease in your glucose, which in turn helps you to correlate the foods that you eat with your glucose response and then make better decisions for your health and sport. When you create more stability and less variability in your average daily glucose, you’ll undoubtedly improve your insulin sensitivity. Couple this with a healthy diet that is high in fiber and low in saturated fats, and you’ll be well on your way toward reducing your risk of acquiring type 2 diabetes.

Increase your longevity and vitality

We all want to live longer and kick butt while doing it. If all you ever do after you use a CGM for the next six months or so (I recommend at least six months of use) is learn to change your diet in a way that reduces your nightly average glucose while you sleep and your 24-hour average daily glucose, you’ll live longer and have more energy doing it. Just that alone will help prevent cardiovascular disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and the healthy diet change will also help prevent cancer. Cutting the crap foods out of your life, such as junk foods, saturated fats, fast food, and foods that “blow up” your blood glucose are changes that will result in improvements in your metabolism and athletic performance. A CGM is not the fountain of youth, but it can keep you accountable to your diet and help you to make better choices.

How do you know that you are low in your glycogen stores?

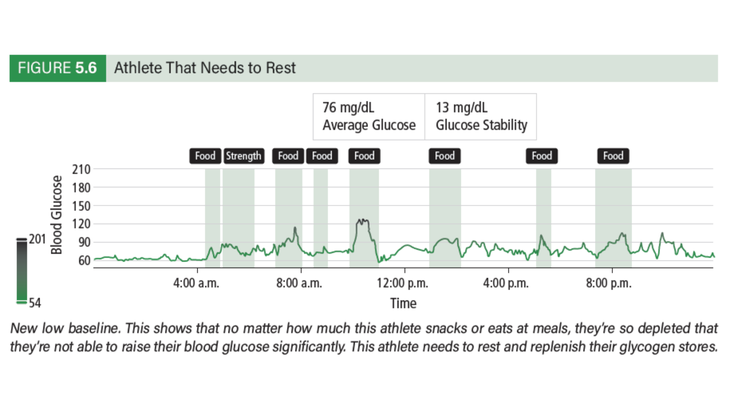

Let’s consider the scenario where you’ve been training hard, are tired, sore, and fatigued over multiple days. What happens with your blood glucose in this case? For example, let’s say your baseline is 90 mg/dL and you regularly cruise in life at this level. Your GPZ is between 110 and 145 mg/dL and when you feel like you’re getting low in blood glucose, you notice your blood glucose at 75 mg/dL pretty consistently.

Now, after three weeks of consistent and intense workouts or competitions, you find that your new baseline is 75 mg/dL, and that you don’t feel hungry or low in blood glucose until around 60 mg/dL. “Wow, this is crazy!” you say. On the flip side, when you ingest carbs before and during training, it’s very hard to raise your blood glucose to 110 mg/dL now, which was the low end previously. Even deliberately trying to spike it won’t raise your blood glucose over 110 mg/dL. Not only that, but it feels like you’re running on “fumes” during your training; you’re constantly on the blood glucose roller coaster and struggling with workouts. This should be an indicator to you that it’s time to rest and recover. See the chart below. Sometimes, that’s just not possible, especially if you’re a professional cyclist competing in the Tour de France. In that case, you would need to eat and drink as many calories as possible consisting of carbs, proteins, and fats. You need to stuff yourself for multiple days while resting to see if you can restore some liver and muscle glycogen; otherwise, it’s going to be game over.

What happens to your glucose in competition?

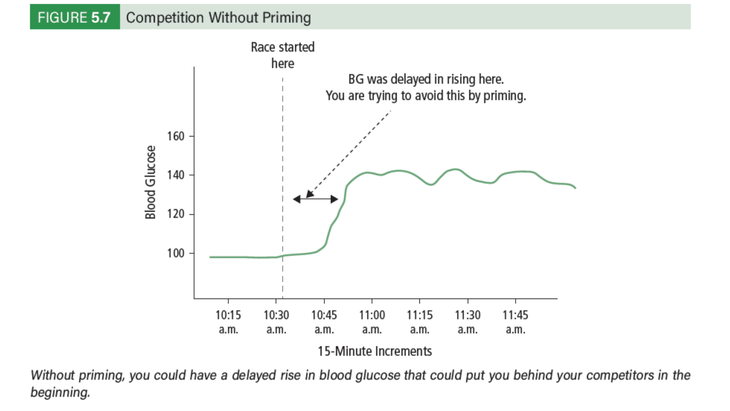

Have you ever watched those Olympic middle-distance runners? They start out fast and just get faster. There is no easing into the effort or ramping into the first lap. There are many competitions where you have to be 100% prepared for maximal effort from the start. In high pressure events like the Olympics, or an important event for you, or even just your first event where you might be anxious or nervous, your body will release adrenaline. This will also cause the liver to release glycogen into circulation in anticipation of your effort. This is a good thing. It’s a natural priming and raising of blood glucose values to prepare you for the event. So you should see an increase in your blood glucose 10 minutes or more before the event even starts. If you’re a slow responder or someone who doesn’t get too worked up by things, including competitions or workouts, then you’ll not see a spike in glucose until about 5 to 15 minutes into the effort, and then you’ll see this delayed spike. This is not ideal for an intense effort, hence the need for priming.

What does it mean if your glucose drops during a workout and continues to drop?

This usually occurs when you’re exercising for a longer period – longer than 2.5 hours – without ingesting any carbs so that you’ve used much of your liver glycogen and there is a reduction in circulating blood glucose. This is hypoglycemia, when you’re low in blood sugar. How much drop is enough to make you feel hungry? How much is enough to make you feel “bonky”? Because everyone’s basal level is different, the drop will be different, and it’s largely dependent on what you’re used to as your norm. If you’re used to running at 130 mg/dL and you drop to 100 mg/dL, you’ll feel like you need food immediately. Or if you’re used to 80 mg/dL and then you drop to 65 mg/dL, you might feel bonky too.

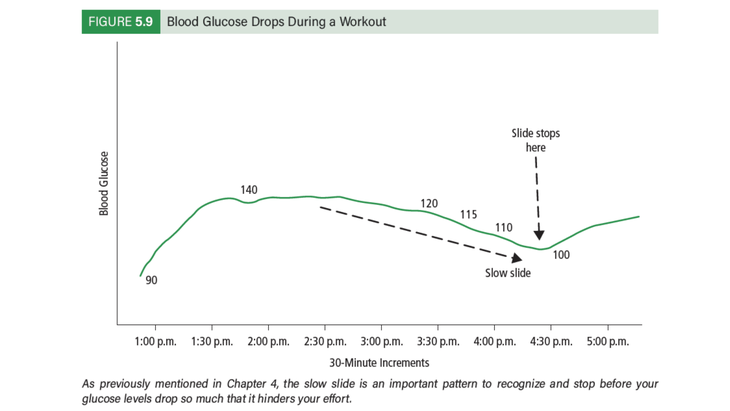

What should you be concerned about from a performance standpoint? You want to minimize those drops so that if you’re on a slow slide from 130 to 100 mg/dL, you recognize it at 110 mg/dL and ingest more carbs (but not too much). See below for a clear example of the slow slide. This will help you to arrest that slide and stabilize your blood glucose at 110 mg/dL, and slowly bring it back up to 130 mg/dL in your optimal GPZ. Your job is to prevent the blood glucose from dropping too much while exercising. In Figure 5.10, we see a clear example of a weightlifter who has low daily basal level, and even after eating a meal and then doing a run, his glucose levels remain very stable and lower than most people.

Optimizing your glucose for workouts and competitions is an important way to ensure that you’re performing at the highest level of your current fitness. It’s not a guarantee of success by any means. That comes down to your training, strategy, coaching and mindset come race day.