The Gear that Made Modern Triathlon

(Photo: Getty Images, Kai-Otto Melau, Jan Hetfleisch)

Triathlon is still a relatively young sport, but it’s come a long way from its roots in the mid-1970s and early 1980s. If you were around back then – or if you’ve seen photos of the gear athletes used – you might think it’s become an entirely different sport. Here’s a look at three key gear evolutions that have had major impacts on the swim, bike and run disciplines in triathlon.

RELATED: Recalled: The Invention of Triathlon

The Evolution of Wetsuits

In the early days of triathlon, wetsuits weren’t a thing at all. Triathletes showed up in Speedo and TYR lap-swimming suits and braved that day’s water temperatures and conditions before hopping on their bikes at T2 in the same sleek swimwear. (Yes, that meant the swim and bike were known for being cold and often confounded by awkward chafing.)

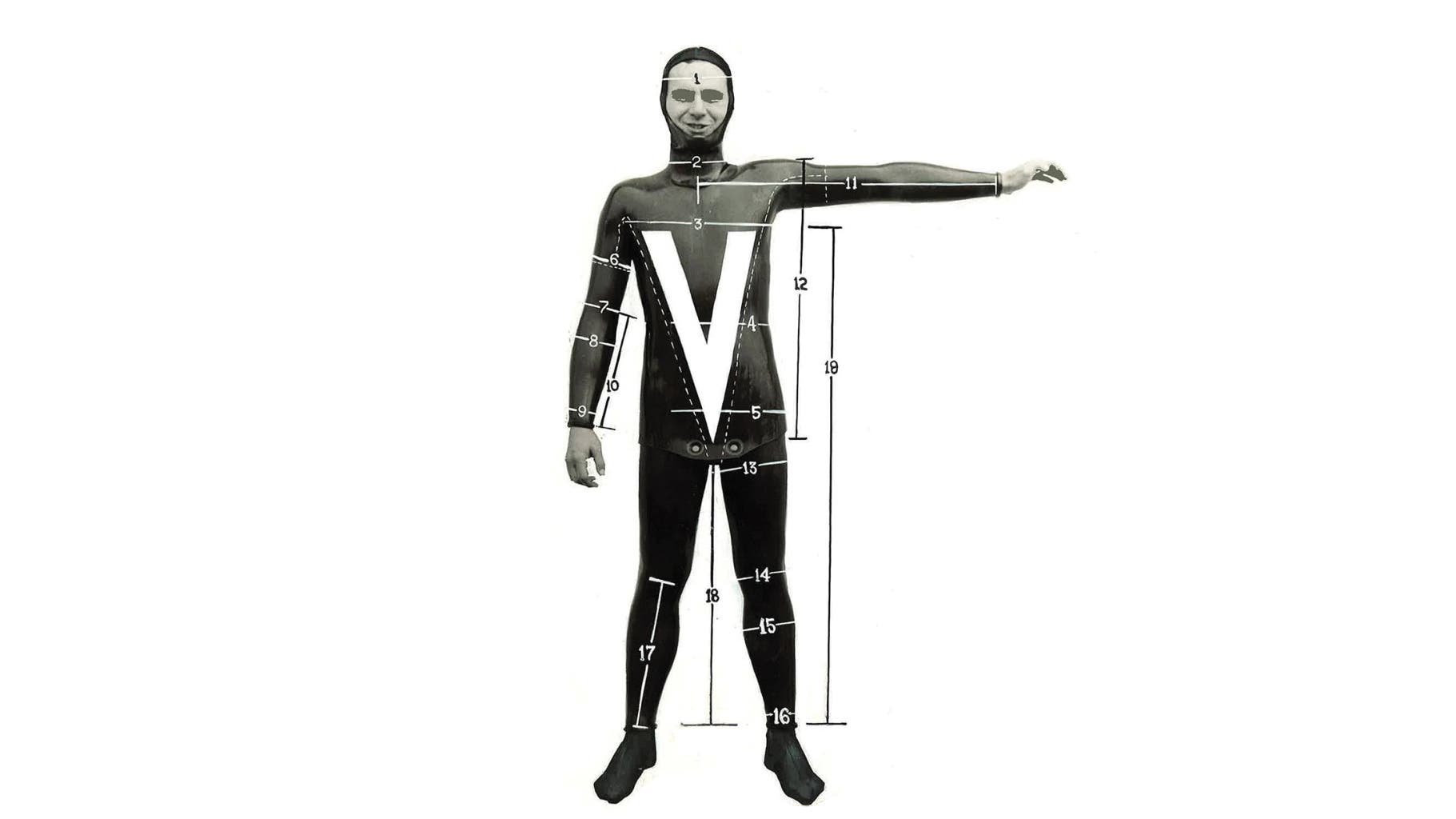

Back then, some triathletes started using surfing wetsuits to stay warm in cold water, but a lack of articulation in the design limited flexibility necessary for swimming. Wetsuits had originated in the early 1950s when University of California physicist Hugh Bradner developed an underwater suit (pictured above) fashioned from rubber and neoprene to keep surfers and divers warm in cold ocean waters.

It wasn’t until 1987 that triathlon innovator and Quintana Roo founder Dan Empfield designed the first triathlon-specific wetsuit aimed at helping triathletes swim more efficiently and faster in open water. Instead of focusing only on warmth, Empfield’s wetsuits combined extremely flexible sections in the shoulders and arms with maximum flotation in the legs and torso.

Empfield conducted a series of tests to investigate the impact of wetsuits. He originally believed that staying warm in the water meant a triathlete could move more efficiently, but he determined that the reality was more about buoyancy. Soon, Quintana Roo wetsuits were all the rage, so much so that the company couldn’t make them fast enough to match the demand. Initially, the brand was making 40 per month, but the demand quickly grew to the need to manufacture 200 per month and then up to 800.

RELATED: The Evolution of the Swimming Wetsuit Design

“I built a wetsuit factory in 1987, not out of choice, but desperation,” Empfield said recently on a post on his Slowtwitch.com triathlon site.

“I designed a triathlon wetsuit in 1986 as a thought experiment, and fell slow-motion-backward into the industry.”

Thanks to Empfield’s revelations and Quintana Roo designs, buoyancy and flexibility gained via a wetsuit was a key factor in the competitive ranks of the 1990s, which is why wetsuits (especially sleeveless “Farmer John” models) became common even in mild-temperature swim conditions. But it also helped break down barriers to entry among age-groupers, as triathlon participation numbers soared in the mid-1990s as newcomers to the sport felt safer and more comfortable in open-water swimming.

In the late 1990s, Yamomoto developed Super Composite Skin (SCS) rubber, which was more durable and less tacky than traditional wetsuit neoprene. A wide range of new brands entered the fray in the early 1990s and early 2000s — including TYR, ORCA, Ironman, Blue Seventy, Xterra, Sumapro, Zone 3 and ROKA — bringing a wide range of performance-oriented innovations. Nowadays modern tri wetsuits off articulated shoulders, offset zippers, thinner necks, advanced leg openings for removal, magnetic closures, gender-specific silhouettes and strategic flotation panels at varying points around the body.

Ultimately, triathlon wetsuits have changed out triathletes swim. They’re designed to help any triathlete become more hydrodynamic in the water by reducing drag while swimming, making it possible to swim more efficiently and faster. That might mean a $150-$200 base model or a $1,000-$1,500 elite model. The key is finding one that works for your physique, fitness and race expectations.

“The moral is, buy the wetsuit designed to make you the fastest, safest, warmest (or least warm, depending on where you live and race), and best fitting,” Empfield said. “This may be the most expensive wetsuit in a brand’s line, but it may well not be.”

The Origin of Aerobars

In the early days of triathlon, there was no such thing as a “tri” bike or a “TT” bike. Back then, carbon-fiber road bikes had just burst on the scene, but they still had curvy, old-school drop bars that gave you the option of riding in an upright position with your hands on top of the bars or in a partial tuck while clenching the down bars. While biking the Queen K Highway in the early days of Kona, the leaders quickly found that pedaling while leaning into a tuck on their drop bars could not only offset the gusting winds but also save some energy in their legs for the marathon they had to run as soon as they dismounted.

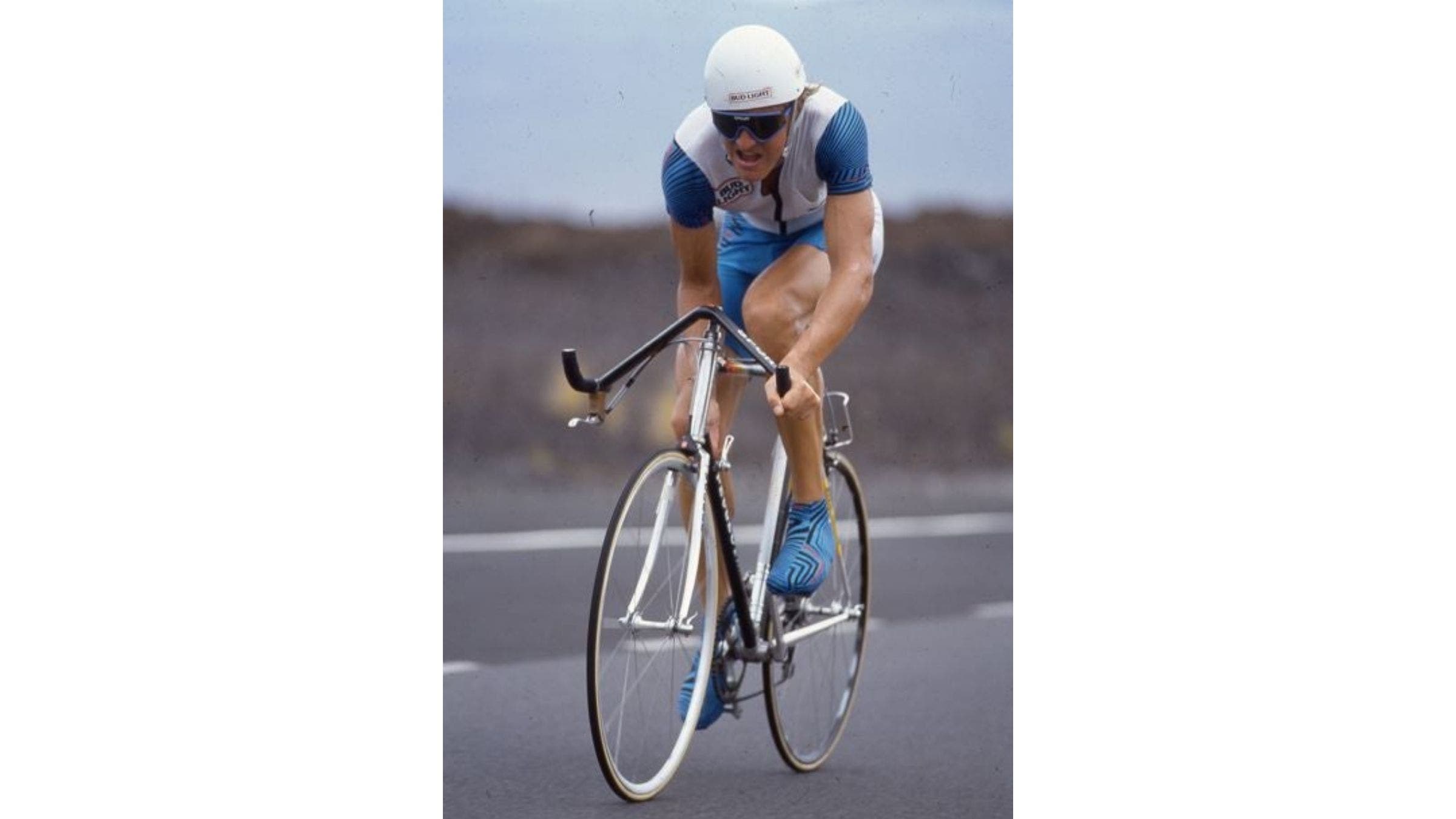

While American cyclist Greg LeMond brought aerobars to the forefront en route to winning a time-trial stage to seal the Tour de France in 1989, it was Scott Tinley who offered proof of concept in triathlon during the 1985 Ironman World Championship in Kona. With Dave Scott, Scott Molina and Mark Allen sitting the race out (in a quasi protest for the lack of Ironman prize money), Tinley affixed a set of dropped cowhorn-style bars to his carbon-fiber Peugeot bike and rode his way into history.

“The old-school network of European cycling kind of poo-poo'ed aerobars for a long time, but, in triathlon, there were no rules at that point, or very few anyway."

The bars were developed by entrepreneur and triathlon pioneer Gary Hooker, who was just getting his AeroSports brand off the ground. Taking cues from aerobar pioneer Toni Maier (an innovator who also developed the world’s first Lycra cycling kit), Boone Lennon (a downhill ski coach who helped Scott USA patent the aerobar concept that Lemond would subsequently use), Richard Bryne (inventor of Speedplay pedals) and Pete Penseyres (an elite cyclist who won Race Across America, or RAAM, in 1984), Hooker shaped the bars out of aircraft-grade aluminum, affixed pull brake handles on the drops and had Tinley test them with a few rides up and down San Dieguito Road in San Diego before sending him to the Big Island of Hawaii with the most unique-looking bike ever seen in Kona.

Not only did Tinley, then 29, break the bike course record with a 4:54:07 split, he took 5 minutes off Dave Scott’s overall course record and won the race with a 25-minute margin in 8:50:54. (Tinley also wore aerodynamic booties over his bike shoes and a white plastic shell of a helmet that offered some semblance of wind resistance.) It was Tinley’s second win and one of eight podium finishes he recorded in Kona as he earned his place in the sport as one of the Big Four, along with Scott, Allen and Molina.

“I went to pick up the bike the morning after the race and noticed a large crack in the bars,” Tinley recalls. “Sometimes it’s better to be lucky than good.”

While aerobars became a way to temporarily convert a road bike for optimal triathlon performance — with bars being clipped on or bolted on — what they really led to was the specificity of modern tri-specific super bikes that offer maximal aerodynamic efficiency. As triathlon evolved and the bike portion was ultimately viewed as an individual time trial sandwiched between a swim and a run, coaches, athletes and bike manufacturers began to understand how a tri-specific cycling form could optimize cycling performance and put an athlete in position to run off the bike as fast and efficiently as possible.

Does that mean you need to invest $5,000 to $10,000 in a triathlon super bike? Maybe, but maybe not. Clip-on aerobars are still a good option for age-groupers entering the sport and bar/stem combos are, too, but a tri bike will offer much more for advanced triathletes who are fit and strong enough to maintain aero position for the majority of the bike section of a race.

Performance-oriented aerobars were discovered almost by mistake, Tinley recalls. In 1984, Bryne had been coaching Penseyres’ younger brother for RAAM in 1985, Jim, who had some unique nutritional needs that required him to take in a lot of calories during a bike ride. Bryne developed a small platform mounted between extension bars that would allow him to access his food. Riding with that setup in a more relaxed position, Bryne found that Jim’s heart rate dropped and he was able to ride more efficiently.

In early 1985, Tinley had trained with a set of fiberglass aerobars made by Bill Goldfoos at AeroLite pedal company. Those Delta Wing bars were super light (about 10 oz.) and the perfect addition to Tinley’s carbon-fiber Look bike, but he ultimately wanted something more durable to race in Kona so he settled on the aluminum cowhorn-shaped bars made by Hooker at AeroSports.

“The old-school network of European cycling kind of poo-poo’ed aerobars for a long time, but, in triathlon, there were no rules at that point, or very few anyway,” Tinley recalls. “A lot of the ideology of the early days of triathlon was about experimenting and looking for advantages to see how we could get faster. It was kind of sexy to think about what we could do about our bars, and shoes and pedals and nutrition. We kind of got to make the rules. It was a tabula rasa situation because we knew what we needed didn’t exist yet.”

RELATED: Are Custom Aerobars Here to Stay?

The Rise of Super Shoes

For years, all running shoes were built on a relatively similar midsole platform constructed from some variation of a copolymer known as ethylene-vinyl acetate or EVA. From its rise in the mid-1970s, it offered runners shock-absorbing cushioning against the pounding impact of the roads. Triathletes, like runners, tended to wear the lightest version of these shoes, and, for the most part, there wasn’t too much differentiation among prominent models with EVA cushioning.

But the early 2000s saw the rise of new running shoe technology that began to increase the running performance in triathlons. The first notable innovation was Newton Running, which running gait guru Danny Abshire developed (with Brian Russell) after making posture-aligning footbeds for Ironman champions Paula Newby-Fraser, Mark Allen, Peter Reid, Lori Bowden, Natascha Badmann. and Scott Molina. Newton Running was the first brand designed to encourage optimally efficient running form and provide increased energy return.

Newton shoes incorporated unique propulsion activators aimed at increasing energy return. Each shoe had four rubber lugs protruding from the bottom of the forefoot. Upon impact with the ground, the protruding lugs pushed into a taut rubber membrane hidden under the lugs, momentarily storing energy before discharging it into the forward momentum of the foot as it entered the toe-off phase of a stride.

Also of note was the geometric profile of Newton shoes. While most running shoes had a heel that was 12 to 14 mm higher than the forefoot, Abshire’s models offered a much more balanced platform with a 1- to 2-mm heel-toe offset, thus helping reduce or eliminate the negative aspects of a heel-striking gait and, as a result, allowing a runner to run more naturally and efficiently.

RELATED: What Makes Super Shoes Super?

Newton rose in prominence among the early adopters of triathlon as Newton-sponsored athlete Craig Alexander became the world’s top long-distance triathlete. Alexander took second in the 2007 Ironman World Championships wearing an early pair of Newtons and then won three of the next four Ironman titles (2008, 2008, 2011), as well as the 2011 and 2012 Ironman 70.3 World Championships. As a result, Newton quickly rose to prominence in the unscientific but significant Kona shoe count.

Hoka One One changed the game soon after by pioneering the concept of maximally cushioned running shoes in 2010. Whereas much of running and triathlon were caught up in the minimalist trend that came after the release of New York Times best-seller “Born to Run,” Hoka went in the opposite direction and created cushy, comfortable shoes with high-stack foam midsoles. But founders Jean-Luc Diard and Nico Mermoud also incorporated a “rocker” or concave design profile that helped runners move through the gait cycle more efficiently, as well as rubber-infused EVA foams that offered more rebound and energy return. Not surprisingly, Hoka shoes grew in popularity among triathletes and was the top brand in the Kona shoe count in 2017, 2018, 2019.

But the innovation that really changed running for triathletes was the incorporation of carbon-fiber propulsion plates into the foam midsoles of running shoes. Reebok had been the first to incorporate a lightweight carbon-fiber support bridge under the arch of its Graphite Road shoe in the 1990s. In the early 2000s, Adidas used a carbon-fiber propulsion plate in the ProPlate racing flat, and Zoot Sports incorporated one into its Ultra Race triathlon racing shoes in 2007. But none of those shoes were able to produce significant energy return, partially because of the limited resiliency of EVA midsoles.

By 2014, Hoka was developing shoes with a curvy carbon-fiber propulsion plate, but it was Nike that would be the first to bring shoes to market in 2017. The theory behind embedding a rigid plate in the shoe was that a runner would create a levering effect with the hyper-resilient Pebax midsole foam that would quickly engage the plate and, as a result, push the foot forward toward the toe-off phase with almost no additional energy expenditure. Those innovations ultimately led to Nike’s Vaporfly line of shoes — first the Vaporfly Elite, then the Vaporfly 4% and eventually the Vaporfly Next%, Vaporfly Next% 2 and Alphafly Next% models — that began to dominate marathons and led to new marathon world records from Eliud Kipchoge (2:01:39 in 2018) and Brigid Kosgei (2:14:04 in 2019).

The rise of super shoes also immediately led to considerably faster Ironman run splits — notably Matt Hanson (2:34:39, 5:54 pace per mile) and Ivan Tutukin (2:35:19) at Ironman Texas in 2018 and Ben Hoffman’s 2:36:09 effort at Ironman Florida in 2019. Not coincidentally, Nike was atop the Kona shoe count in 2018 and 2019.

At Ironman Tulsa in early 2021, Patrick Lange ripped off a 2:36:45 run split en route to a 7:45:22 overall victory, but Jan Van Berkel (2:39:05), Daniel Baekkegard (2:44:34) and Denis Chevrot (2:36:03) were also flying, as was women’s run leader and race runner-up Katrina Matthews (2:49:49, 6:29/mile pace).

RELATED: How Fast Can the Fastest Pros Run in Ironman?

Now every major brand has a super shoe for marathon running, including HOKA (Rocket X), Nike (Vaporfly Next% 2) ASICS (MetaSpeed Sky), Adidas (Adizero Adios Pro 2), Puma (Deviate Nitro Elite), New Balance (FuelCell RC Elite v2), Brooks (Hyperion Elite 2), On (Cloudboom Echo) and Saucony (Endorophin Pro 2). Can you still race in a standard running shoe with traditional foam, such as the Saucony Kinvara, HOKA Clifton 8 or Nike Pegasus 38? Absolutely, but the upside to investing in a pair of super shoes, especially the ability to train faster and recover quicker.

“These shoes, they’re clearly an advantage from an energy return standpoint,” Hoffman said. “Clearly you’re getting a little bit extra speed and pop if you’re running in them properly. But the way they’re constructed, the technology of the foam itself is something where you’re getting more recovery too. I believe that’s a huge piece of it, too, that you tend to not feel as beat up after a longer run when you’re using those shoes. It allows you to do more miles, allows you to bounce back quicker, allows you to train neuromuscularly at a faster pace, all of those things come together to create a pretty significant improvement in the run.”