How Will the Tokyo Olympics Happen? Should They?

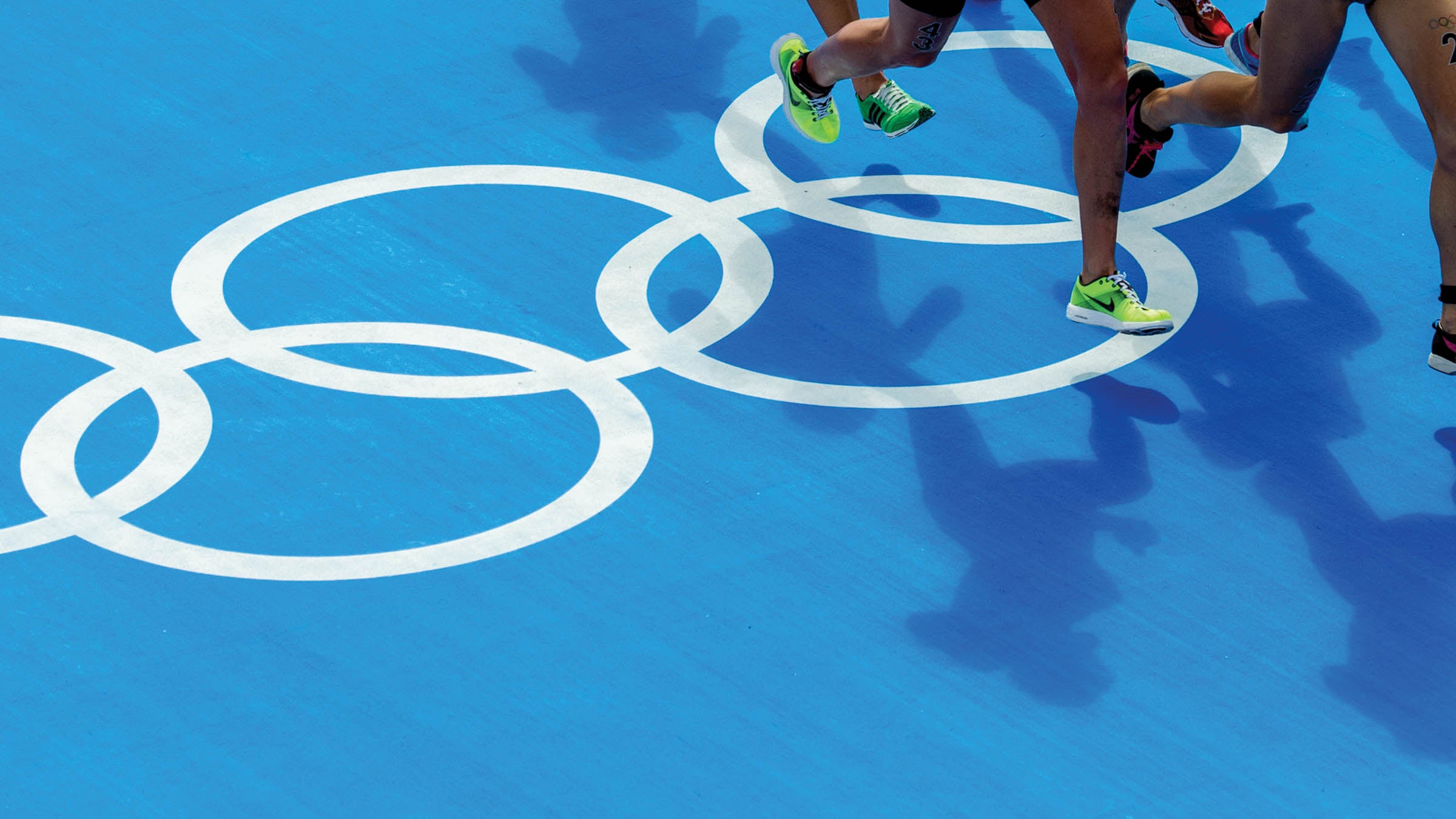

(Photo: Getty Images)

Updated: July 8, 2021

The Olympic and Paralympic Games are something that take years of meticulous planning and behind-the-scenes work to execute. Committees are formed and event directors plot out the specifics for each sport. Athlete housing and logistics are scheduled. Media operations are built from scratch. Years of work go into these finely-tuned plans. Yet, for the Tokyo Games, those plans have already been tossed out and reworked again and again and again.

First, the 2020 Olympics were postponed in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Then, with the need to add an entirely new layer of safety measures outlined in a series of revised Olympic playbooks, the organizers have adjusted them until they’re down to the wire. The specifics of what COVID dictates will keep changing right up until the Games start. It makes for a nearly impossible task with a series of endlessly rising hurdles. Can the organizers pull off what no one has ever faced? Should they?

A Sea of Uncertainty

Writing by email on May 17, just two months before the Olympics were scheduled to start, Tatsuo Ogura, project director of the international communications team, said: “Taking into account everyone who holds tickets for the Games and has been looking forward to attending, and the feelings of the families of athletes around the world who won’t be able to come to Japan to see them compete in person, we are using all of our resources to be ready. The decision won’t come until the last minute, but while we are ultimately preparing to hold the Games without spectators, we are hopeful that the situation will allow for audiences to watch in person. This line of thinking remains unchanged, but no final decision has been reached yet.”

Update: On July 8, the International Olympic Committee and Japanese organizers announced a ban on spectators at all Olympic venues. The decision was made on the heels of Japaese Prime Minister Yoshihde Suga’s announcement that a state of emergency would be declared due to rising coronavirus cases in Tokyo.

In other words, everyone involved—over 10,000 athletes, tens of thousands more support staff, organizers, officials, volunteers, medical and security personnel, and members of the media, international federations for 33 sports, national federations and Olympic committees from 205 countries, 81 sponsor companies, millions of fans, and almost double all of that again for the Paralympics—is in the unprecedented situation of trying to prepare for a massive, complex event without knowing if it actually is going to happen. All of this planning and infrastructure has to be dropped in the middle of a sea of uncertainty, against the backdrop of a growing rumble of popular opposition locally. That’s where Tokyo 2020 finds itself right now in the middle of 2021. But how did we get here?

Engraving these Olympics in people’s minds as a bad memory could become a negative legacy on Japan and the Games that will result in nearly unlimited future loss.

Dollars & Cents

Looking at the Tokyo Olympics from an economic standpoint, it was inevitable that the pandemic was going to result in a loss. The question is: How big of a loss? According to calculations by Katsuhiro Miyamoto, professor emeritus of economics at Kansai University, the initial postponement from 2020 to 2021 caused a loss of 640.8 billion yen, approximately $5.9 billion, in missed economic opportunity. Holding the Games with domestic-only crowds at half-capacity would bring the loss to approximately $14.9 billion. The recently announced spectator-free Games would lose an estimated $22.2 billion, and an outright cancellation would result in $41.4 billion in revenue gone. None of this even includes the massive amount of money already spent on the Games themselves.

After the initial postponement and then after the decision not to allow international spectators, there was nothing the organizers could do that wasn’t going to result in an economic outcome far distant from original forecasts, with no return on investments already made. The main question became simply how to reduce losses any further. Of course, Professor Miyamoto stresses that in the midst of a global pandemic the main focus is on human life and health. The loss will be far greater if health and safety concerns aren’t managed. “With available sickbeds becoming a scarcity, it is essential to provide the public with convincing explanations and to secure an adequate medical system to support the international athletes who will travel here,” he warned. “If they try to force their way ahead without these, it may become an international issue and we may lose even more beyond these calculations.”

Engraving these Olympics in people’s minds as a bad memory could become a negative legacy on Japan and the Games that will result in nearly unlimited future loss.

The Cost of Postponement

Since the initial postponement of the original 2020 dates, plans for the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games have evolved along these lines:

| Mar. 24, 2020 | The Games are postponed to the estimated loss of $5.9 billion. |

| Mar. 30, 2020 | The IOC establishes new dates. The Olympics are now scheduled to start July 23, 2021, and the Paralympics will begin on Aug. 24, 2021. |

| Nov. 10-Dec. 21, 2021 | Ticket holders are offered a chance for refunds; domestic ticket holders request refunds for 810,000 tickets with an estimated total value of over $80 million. |

| Feb. 3, 2021 | Tokyo 2020 organizers release the first Olympic playbook, an outline of COVID-19 countermeasures planned to make the Games possible. |

| Mar. 20, 2021 | The decision is made to bar spectators from overseas. More ticket refunds are expected. |

| Apr. 24, 2021 | Triathlon’s Asian Championships held in Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima. Athletes from other Asian countries are isolated in a quarantine bubble throughout their stay in Japan. |

| Apr. 25, 2021 | A state of emergency is declared in Tokyo for the third time and in three other prefectures. Initially set to continue until May 11, the declaration is extended until the end of May. |

| Apr. 28, 2021 | The second edition of the Olympic playbooks is released with more detailed (but not final) info. |

| May 15, 2021 | World Triathlon Championship Series race is held in Yokohama, featuring elite athletes from around the world in quarantine setups—despite strict immigration restrictions. |

| May 16, 2021 | Yokohama’s age-group race is held with approximately 1,500 participants. |

| June 2021 | Final edition of Olympic playbooks released. |

| June 2021 | Decision made to allow 10,000 domestic spectators or 50% of venue capacity—with masks, and no shouting or cheering. |

| July 8, 2021 | Prime Minister Yoshihde Suga announces a state of emergency; the IOC bans spectators at all venues. |

Calls for Cancellation

Even now, well over a year since the Olympics were originally postponed, Japan is riding out a fourth wave of infections. The number of cases and deaths is low, a fraction that of places like Europe and the U.S., but with virus variants now beginning to spread, the Japanese population’s anxiety is increasing every day and support is growing for canceling the Olympics.

In mid-May, polls by five major Japanese news organizations showed between 37% to 60% support for outright cancellation. (There was greater support for cancellation when postponement wasn’t given as an option.) By mid-June that opposition still sat at just over 30%. The sentiment is no doubt partly combined with people’s frustration with the Japanese government’s repeated calls for them to voluntarily stay home and its failure to roll out vaccines effectively. Japan’s current fully vaccinated rate as of press time is only 7.3%—placing it below the worldwide average of 9.6% and one of the lowest among developed nations.

The International Olympic Committee has offered to vaccinate all athletes at the Games and Pfizer and BioNTech have committed to providing doses, but there is a sense that some athletes feel reluctant to prioritize themselves, especially in countries (like the host nation) where vaccines haven’t even reached all of the most at-risk residents and healthcare professionals.

“A lot of us are worried,” said Japanese triathlete and Olympian Ai Ueda, who is also a member of Japan’s Olympic Committee’s athlete commission. “With people suffering and the number of infected going up, should the word ‘Olympics’ even be a part of the conversation? Athletes [like swimmer Rikako Ikee] have people on their social media telling them to drop out of the Olympics, and [the track and field test event] had an [anti-Olympics] demonstration outside the stadium while athletes were competing. It’s not the kind of atmosphere where you can just come out and say, ‘I’m going for an Olympic medal’ like you used to. I can feel that it’s a totally different situation from anything we’ve experienced before.”

And the Balance Shifts

Yet, sports have marched on. Athletes have trained as best they can and, in May, World Triathlon reopened the Olympic points qualification window. On May 15, the World Triathlon Championship Series race in Yokohama—the final automatic Olympic qualifying event for many athletes—was held on public roads less than 20 miles away from Tokyo, where a state of emergency was in place. Fans and locals mostly respected organizers’ requests not to spectate along the course, leading to smaller crowds, and no protests against the event or the Olympics were reported. On the course itself, and again in Leeds in early June, you could see a shift in the balance of power among elite triathletes.

Yokohama women’s winner, 23-year-old American Taylor Knibb, and third-place men’s finisher Morgan Pearson surprised many to earn spots on the U.S. team and emerge as new stars. In Leeds, Pearson followed that up with a second right behind British up-and-comer Alex Yee. For all three, the extra year was a gift.

But some who were favorites a year ago have struggled. 2019 world champion Katie Zaferes managed to snag the last spot on the U.S. team via discretionary selection—but finished mid-pack in both early season races. And France’s Vince Luis, almost a lock for a gold in 2020, was a worryingly lackluster sixth in Yokohama and a DNS in Leeds. All of a sudden, it seems there are new medal favorites.

Among Japanese athletes, nobody benefited more from the Olympics’ postponement than Ai Ueda. In 2019 she suffered a plantar muscle rupture—a serious injury that took over a year to completely heal. Having the extra time to heal has made a huge difference for her. It’s also been a year of evolution among the Japanese men, with Kenji Nener emerging after national and regional championship wins.

It’s not the kind of atmosphere where you can just come out and say, ‘I’m going for an Olympic medal’ like you used to. I can feel that it’s a totally different situation from anything we’ve experienced before.

Swaying the Public

Taro Shirato is a former pro triathlete and Ironman Japan Hokkaido organizer who is now a member of the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly. His duties include working on the Olympic and Paralympic Games. He’s confident that if the Olympics are held without spectators they could be staged without any issues.

“I think the biggest concern that Japanese people have about the Olympics is the fear of the large number of athletes and others from overseas spreading infection,” he said. “The reality, however, is that the athletes will be isolated from the general public in a bubble and, that being the case, it is very unlikely that infection could spread. Since athletes and other people involved in the Games will have PCR tests performed every day, it will actually be far safer inside the isolation bubble than in the city of Tokyo. International competitions in different sports are being held successfully using the bubble isolation method, and athletes around the world are getting used to what that entails. I don’t see any reason the Olympics couldn’t be held without spectators.”

It’s not the logistics, but public opinion that is truly the critical factor in making the Games happen. Echoing Professor Miyamoto, Shirato emphasized that transparency and clear, honest explanations are necessary. “Nobody is going to be persuaded unless you give them the right information the right way,” he said. “The only way to reduce opposition is to explain things correctly.”

How the ‘Bubble’ Works—Really

To that end, the specifics of how these bubbles will work and be managed is key. “The Hatsukaichi and Yokohama competitions were effectively Olympic test events,” said Yoji Sakata, director of the JTU Marketing Business Bureau, which was involved in the management of both triathlons.

Athletes and support staff had to be completely isolated from the general public—from arrival at the airport to transfer to the hotel and all the way through to departure. Sub-bubbles within the larger isolation bubble were also established to keep people in smaller fixed groups for training, Sakata said. Dedicated training facilities were set up with treadmills, bike trainers, and an indoor pool—with a fixed schedule organized so that each smaller group could train privately at preset times. The most difficult aspect for Sakata and the other organizers was creating an environment within these constraints that would still let athletes concentrate on their race. “If the athletes perform well,” he said, “I think that will convince viewers of the value of what we’ve done.”

To keep things fair and prevent a home court advantage, Japanese athletes also had to go through the inconvenience of living in the isolation bubble like their international competitors for the same period of time. Japan’s rising star Kenji Nener went through the process in both Hatsukaichi and Yokohama. “At Hatsukaichi, we could only leave our hotel rooms for one hour per day to train in the training room inside the hotel, bike only,” he said. “In Yokohama, we were allowed to train outside the hotel, but only under strictly controlled conditions. We were taken to the gym and pool by private bus and could swim, bike, and run. It was surprising, and I was really grateful that they went to such lengths. There were some headaches, but you have to appreciate how hard it must have been for the organizers to pull this off. And costly, extremely costly.”

There were three PCR tests during the week-long quarantine, Ueda added, and meals left outside the hotel room door three times per day—which had to be eaten in the rooms. Along with the dedicated one to two hours of daily training, athletes got one hour to test ride the course before the start, which left some stressed.

To keep things fair and prevent a home court advantage, Japanese athletes also had to go through the inconvenience of living in the isolation bubble like their international competitors for the same period of time.

“Some of the athletes were complaining,” Nener said, about all the restrictions and red tape, “but I felt like they should’ve been grateful for what we had.”

The measures tested at both triathlon events were also used at the official Olympic test events in diving, volleyball, track and field, and the marathon—giving organizers a crucial opportunity to assess and finesse their logistics and giving the athletes a taste of what to expect this summer. As at WTCS Yokohama, all four test events included international competitors, and out of nearly 8,000 athletes and support staff only one case of COVID-19 was found—a diving coach who tested positive at the airport after arriving in Japan and was quickly quarantined. As of this writing, there has been no spike in cases related to any of the events.

According to the third edition of the official Olympic playbooks, during the Games the entire Olympic Village will be a bubble. Under the supervision of a designated compliance officer appointed by each National Olympic Committee, athletes and other international staff involved will have to register a detailed itinerary for their entire stay in Japan, install multiple tracing apps on their phones, and take PCR tests prior to departure for Japan, immediately after arrival, and daily throughout their stay. They’ll be barred from using public transportation, eating out, or having any other contact with the general public, and will be restricted to the Olympic Village and to official transportation to and from training and competition venues. Contact with other athletes and with the media will be minimized as much as possible to reduce the risk of community spread within the Village. Any positive cases or people experiencing symptoms will be immediately quarantined, with additional protocols for their close contacts, and everyone is asked to leave Japan as soon as possible after they’ve finished competing. Potential penalties for violating the Playbook guidelines range from fines to disqualification to deportation. It’s not exactly the kind of atmosphere you’d usually expect at the Games.

What Kind of Olympics Are We Going to End Up With?

With so many variables still to be determined, it’s impossible to say for sure what kind of Olympics this will be. But it’s safe to say that the Games will demand flexibility and adaptability from athletes and, more than ever before, superhuman powers of concentration and focus. In a regular year, the Olympics already put huge amounts of pressure on athletes. Add to that uncertainty and the threat of the unexpected, and there’s never been an environment of this kind at this level of sport. If you thought Olympic triathletes were fast before, imagine having to be that fast on the right day with the right quarantine pre-race training, after getting all the right paperwork and tests, amid a flurry of unfamiliar and changing restrictions. How will people perform?

And the fans? Around the world it’s a mixture of anticipation, worry that overshadows simple enjoyment, indifference in the midst of so much else, and hope that the Olympics can be a net positive after a year-and-a-half of pandemic life.

“I’m feeling excited for the Games but also increasingly nervous and concerned,” said Dave Robertson, an Australian who went to the 2019 Olympic triathlon test event in Tokyo.

“I would say at the moment that interest levels in the Olympics are pretty low. People are still very much focusing on getting life back to normal and being able to enjoy normal things again, like seeing family and friends,” said U.K. resident and fan Tim Williams.

Costa Rican Arturo Delgado had planned to travel to Tokyo to see the Olympics but was forced to cancel his plans. “Even so,” he said, “I am super excited about the tri and will watch it on TV for sure. I am hoping for a fun Games and will spend hours a day following my favorite competition ever, the Olympics!”

And in Tokyo itself, all those feelings are mixed up together on a heightened scale. There’s worry, concern, anxiety, excitement, anticipation, and hope.

“I’d like to see the Games go ahead for the athletes’ sakes as well. I hope that will leave a positive impression in everyone’s minds, like the Rugby World Cup held in Japan in 2019, and that it’ll be something everyone can be happy with once it’s done,” said Tokyo’s Masaki Kusunoki.

In all this uncertainty, there’s one thing that’s certain: The Olympics have arrived at a point where they must demonstrate value in new ways. Will we see the true significance of the Olympics when we watch an athlete deliver a performance that drives away all the anxiety, the dissatisfaction, and the opposition? Or will it feel as empty as the stands? This is when sport’s true power to inspire will be put to the test.