Kona Coverage: What Happened To The 2:40 Marathon?

Why has it been so long since a triathlete has hit the 2:40 marathon mark at the Hawaii Ironman?

When the first Hawaii Ironman in 1978 was won by Gordon Haller on the strength of a 3:30 marathon, nobody could have guessed that participants in future editions of that race would run a full 50 minutes faster.

As athletes figured out Ironman training and racing, the top run splits got faster each year. In 1981, a 19-year-old college student named Joseph Kasbohm ran the first sub-3:00 marathon in the Hawaii Ironman. Three years later, Dave Scott lowered the run course record to 2:53:00.

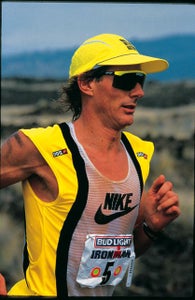

That had to be the limit, people thought. Not so. In 1989, in their epic “Iron War”, Mark Allen (who won the race) and Dave Scott recorded run splits of 2:40:04 and 2:41:03, respectively. And as Dave Scott never tires of pointing out, bike-run transition times were included in marathon splits back then, so both he and Allen actually covered 26.2 miles in less than two hours and 40 minutes.

At that time, nobody could have guessed that 20 years later, those two marks would remain the fastest in the history of the event. In fact, for several years the elite men’s run times in Kona regressed. In 2002, Tim DeBoom won the men’s title and recorded the fastest run split of the day with a time of 2:50:22.

Why did this regression happen? Why does Mark Allen remain the only 2:40 marathon runner in the history of the Hawaii Ironman? Will it ever be done again?

One can come up with a long list of speculative answers to these questions, none of which can be proven or disproven. Some argue that 1989 was an anomaly, the only year in which an athlete capable of running 2:40 actually had to run 2:40 to win. Others make the inevitable and soft-headed talent dearth argument. Still others contend that the drastic increase in prize money that occurred after 1989 led to a more cautious style of racing.

Undoubtedly, some of these speculations have merit. But I believe that the truest explanation for the disappearance of the 2:40 marathon in Kona is systemic rather than atomistic. Performance ebbs and flows happen all the time throughout endurance sports, and they follow predictable patterns. A period of historically soft performances will suddenly end when a single athlete breaks through and does something that has never been done before, or has not been done for a while. Then suddenly the floodgates open and lots of other athletes begin to perform at the same level. But after a while the wave crashes and (to mix metaphors) another season of famine ensues.

This pattern was seen just this year in American track racing. Way back in 1996, Bob Kennedy became the first American to run under 13 minutes for 5000 meters. Like Mark Allen’s 2:40 marathon, Kennedy’s mark remained untouched by a whole generation of gifted American runners that followed him. Then Dathan Ritzenhein crossed the 13-minute barrier this summer, breaking Kennedy’s American record in the process. Less than two weeks later, another American, Matt Tegenkamp, ran 12:58.

Tegenkamp has been around for a while, but he did not run sub-13:00 until Ritzenhein did. Did Tegenkamp run sub-13:00 because Ritzenhein ran sub-13:00? Tegenkamp himself thinks so.

Inevitably, something very similar will happen in the Hawaii Ironman marathon. The right person will meet the right circumstances and match or beat Mark Allen’s historic time. That performance will raise the bar and usher in a new Golden Age of fast running in Hawaii. Some competitors who have raced in Kona for years already will find themselves suddenly running four and five minutes faster.

Mark my words.