The Fight Against Pseudoscience, Bad Training Advice, and Nonsense

(Photo: Heidi Carcella)

In the mid- to late-1800s, more than 20,000 Chinese immigrants descended on the United States to work on the Transcontinental Railroad. They were paid less than American workers for the most grueling tasks involved in building the 1,900-mile rail line, shoveling 20 pounds of rock over 400 times a day in the middle of snowstorms, rock avalanches, and accidental explosions. To cope with the inevitable aches and pains, these workers often used a balm made at home from the oil of the Chinese water snake, rubbed into their joints every night before bed.

The elixir seemed to work, perhaps due to its high concentration of what we now know as Omega-3 Fatty Acids. When Americans caught wind of the pain-relieving properties of snake oil, however, they set out to make and sell their own—only the new version contained zero percent snake. Instead, swindlers filled bottles with a mixture of mineral oil, beef fat, pepper, and turpentine. Without the fatty acids, the so-called “snake oil” didn’t work. What was once a legitimate treatment was bastardized into a scam.

Today, “snake oil” is shorthand for a fraudulent product or service wrapped in the guise of legitimacy. It can be found in just about every facet of daily life, from beauty creams that promise to eliminate wrinkles overnight to juices that claim to detox the body more efficiently than the organs specifically designed for that purpose. And perhaps the most eager audience for snake oil are consumers in the exercise industry, where just about everyone is looking for a shortcut to becoming fitter and faster. Endurance athletes might be the most susceptible of all.

“Any gains in health and fitness take time and effort to achieve,” explains Dr. Nick Tiller, a researcher at the Institute of Respiratory Medicine & Exercise Physiology at Harbor-UCLA. “If you want to get bigger and stronger, if you want to get leaner, increase your endurance, or improve your cardiovascular health, it doesn’t happen overnight. It’s like training for a marathon or triathlon; good preparation takes months or years. It’s a long, laborious process, and there’s a really good chance that endurance athletes will start seeking out products and practices to expedite their performance.”

Athletes don’t have to look far to find these shortcuts. They pop up in Google search results and Instagram ads, set up massive displays at health food stores and race expos, and appear in articles or blog posts that breathlessly claim they’re the “next big thing” for athletes. Modern-day snake oil for endurance athletes comes in pill form, as well as powders, creams, liquids, packaged foods, footwear, clothing, exercise machines, recovery tools, pillows, bedsheets, apps, training plans, cookbooks, coaching, and wellness centers. Tiller’s job as a researcher is to investigate and debunk the extraordinary claims and buzzwords athletes so readily buy into.

“There are people selling all types of products and practices,” says Tiller.

“Vitamin injections, intravenous drips, fad diets, supplements, compression tights, magic shoes, clothes that help you burn more calories, and drinks with added oxygen: If you can think of it, somebody has already made it. They're already selling it, on little science and baseless claims.”

Tiller says many products or so-called “experts” make scientific-sounding claims to efficacy, but the science simply isn’t there. When one takes the time to investigate extraordinary promises made on the packaging or on social media, as Tiller does, they more often than not discover a house of cards. “When you dig a little bit, beneath the surface, below that superficial layer, you find that actually, these products or practices don’t really align with what we understand as science,” says Tiller. “They’re not evidence-based, they don’t follow logic and reason, and they don’t really conform to how our bodies actually work. But most people don’t investigate. They just believe and buy. That’s partly because of our innate conditioning for quick fixes, and it’s partly because we want the claims to be true and haven’t developed the critical faculties to question our beliefs.”

Snake oil is not new, but the speed and frequency at which we can distribute it is. The internet —social media, in particular—has resulted in us being bombarded with overwhelming amounts of data and information. It is available 24/7, literally at our fingertips. Athletes don’t always have the critical faculties to distinguish information from misinformation, meaning they’re more susceptible to pseudoscience, shoddy products and bad advice. As a result, endurance athletes are paying the price.

So easily fooled

At the 2016 Olympics, swimmer Michael Phelps made waves with a series of perfectly round red bruises covering his body. The marks were the result of cupping, a procedure based in ancient medicine in which cups are placed on top of the skin, creating a vacuum that sucks the skin into the cups themselves (and leaves a distinct red mark, much like a hickey on a teenager’s neck). Proponents like Phelps claim cupping stimulates blood flow to the area, thereby loosening muscles and tendons.

As a result of Phelps’ evangelism about cupping, everyday athletes soon started sporting the tell-tale hickeys of the now-trendy recovery practice. However, there was (and still is) no scientific or medical evidence that cupping provides any benefit. “Stimulating blood flow” is a vague phrase that sounds impressive, but doesn’t actually have any effect at the level of the muscle—that’s simply not how the body works. A 2018 review in the Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine concluded that “no explicit recommendation for or against the use of cupping for athletes can be made.” The practice can have side effects such as scars, burns, and infections. Yet some athletes still swear by cupping, and claim their personal benefit as proof that it works. But anecdotes are not evidence, warns Tiller.

“If I want to learn how to train like Michael Phelps, then Michael Phelps is the world authority,” says Tiller. “But is Michael Phelps a renowned expert in recovery strategies? Does he understand human physiology enough to promote cupping as a viable therapy? I’d argue he’s probably not, because he only knows what works for him. He’s not a scientist.”

That’s not to say Phelps doesn’t experience a benefit from cupping. One can believe something works without it actually working. This is what is known in science as the “placebo effect,” where the power of suggestion can create a small-but-noticeable improvement in reported symptoms or performance. Placebo results in powerful psychobiological effects. But thinking you’re stronger or faster isn’t necessarily the same as being stronger or faster.

“Suggestion is not the same as a real physical effect,” explains Tiller. “I could give you a sugar pill and tell you it was caffeine, and you’d probably report feeling effects on your athletic performance. But if I gave you actual caffeine, that’s a stimulant which is very well-studied. It would have actual physical effects on the body because caffeine is a real supplement that has a real effect. The sugar pill only has psychological effects. We have to be careful about how we sell these to athletes because there are downstream consequences of selling placebo products.”

The placebo effect can apply to just about everything. If you believe taking a certain supplement before a workout makes you faster, you might push harder in that workout. If you think wearing bioceramic-infused pajamas makes you feel better the day after a hard session, you might actually walk with a smidge less stiffness. The human brain may be the most complex organ in the body, but it is also the easiest to fool. Knowing this is the first step to thinking critically about pseudoscience in endurance sport. As scientist Richard Feynman once said,

“The first rule is that you must not fool yourself - and you are the easiest person to fool.”

The more you think you know, the more you don’t

It is generally agreed that to find the best advice on training, nutrition, or recovery, endurance athletes should consult with an expert. Where things begin to diverge is in the definition of “expert.”

Someone who dispenses nutrition advice, for example, may be a Registered Dietitian (RD), nutritionist, or health coach. Only one of those titles—RD—has a clear nationwide credentialing process that qualifies the person to make specific dietary prescriptions. Yet anyone can claim to be a “nutrition expert,” and many do; there is no shortage of people giving nutrition advice on the internet. But one 2019 study found that only one out of nine leading bloggers dispensing such advice actually provided accurate and trustworthy information. The rest gave outdated, inaccurate, and potentially harmful information.

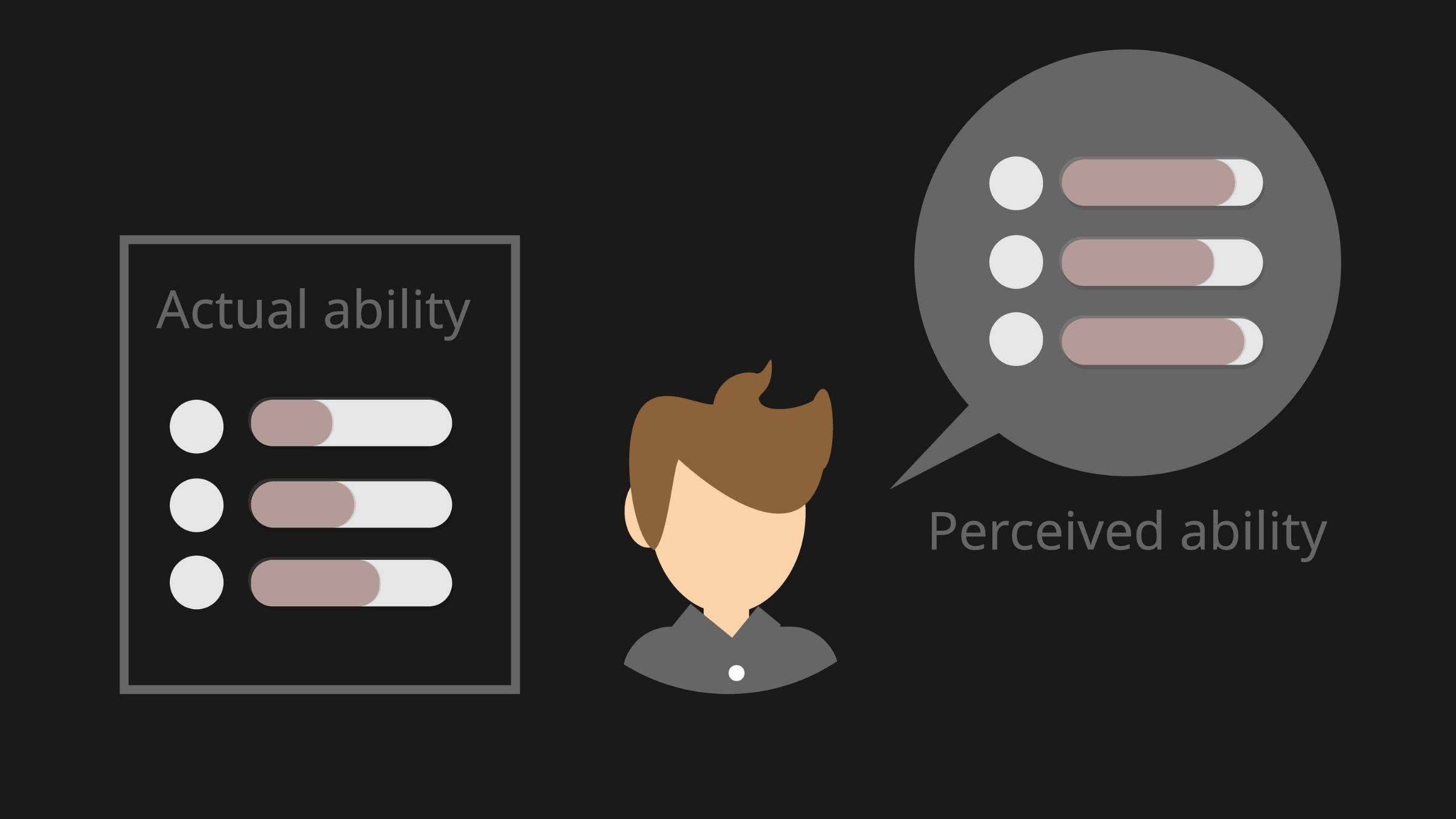

How can so many people be so confident, and yet so wrong? It might not even be their fault. Dr. Phillip Sullivan of Brock University says the Dunning-Kruger effect could be to blame.

“The Dunning-Kruger effect is a mismatch between how good someone objectively is and how good they think they are. People who are poor at something aren’t aware they’re poor at it,” Sullivan explained. “In fact, they think they’re adequate or maybe good. It’s a global phenomenon, seen in everything from driving ability to IQ tests and even sense of humor.”

Sullivan studies the Dunning-Kruger effect in coaching, where he has noted the same disconnect between perception and reality. In a 2019 study investigating the Dunning-Kruger effect in sport coaches, Sullivan and colleagues found that when the ability and efficacy of coaches were evaluated using objective data, skill and perception didn’t always line up.

“At the two extremes of coaching ability—those that aren’t very good and those who are very, very good—their self-assessment is a little off. The people who are very poor tend to think that they are better than they are, while the people who are very, very good tend to think that they’re a little relatively worse than they are.”

In other words, the less a coach knows, the more they think they know. This can lead to an overconfidence that prevents the coach from thinking critically about what they’re doing. “Overconfidence and a lack of self-reflection result in someone who knows only a little bit, but feels they’re qualified as an expert,” Sullivan said.

Though various organizations in running and triathlon have coaching certification and credentialing programs to train people in evidence-based training and nutrition strategies, they’re not required to actually become a coach. Anyone can write a triathlon training plan, blow a whistle at a track workout, or host an Instagram Live to answer questions about nutrition. If they’re confident enough in what they’re saying, they may even be paid a lot of money to do it. But that doesn’t guarantee their advice is sound.

“It’s not hard to draw the lines to connect the dots between an incompetent coach who doesn’t know they’re incompetent and bad outcomes like injuries,” Sullivan said. “If I don’t know how athletes should properly warm up, but I have my own thoughts, I might have my athletes stretching in a non-functional way, maybe even a dangerous way before they go out and compete.” This incompetence is seen in many realms of endurance sports: training plans that overload athletes, drills that cause injuries, nutrition and weight-management advice that can cause complications like Relative Energy Deficiency Syndrome (RED-S).

Sullivan says the most effective coaches and athletes are not the ones who claim to know everything; they’re the ones who are willing to admit what they don’t know. “People who are actual expert coaches typically have a lot of experience, development, and mentorship throughout their entire career. Athletes and coaches, by and large, tend to be a confident bunch. But you can still be confident and also actively, critically reflect on yourself. People who look for their own weaknesses are more likely to seek out legitimate standards of knowledge and competencies, to learn more and be willing to change their thinking based on a high standard of evidence.”

How to change your mind

The blessing of modern technology is that information has never been easier to find. The curse of modern technology is that information has never been easier to find.

“It’s not hard to find support for your point of view, whatever it is,” Sullivan said. “You can deliberately seek out people who agree with you, no matter how unconventional your ideas are. You can look for things that reflect well on you and people who agree with what you’re saying. Your evidence might not be based on anything more than what you’ve experienced, but when you live in an echo chamber, your ideas are reinforced as fact.”

“There’s this thing called confirmation bias, where we’ll see people ignoring evidence that contradicts their beliefs, and accepting much more favorably the evidence or the data that confirms their pre-existing beliefs,” Tiller said. “If you badly want something to be true, you’ll only look for evidence that confirms it, even if it’s not the best quality.”

Breaking into echo chambers is a constant battle for researchers, who dedicate themselves to answering questions in a rigorous, controlled manner. A scientist can spend years studying a very specific topic in incredible depth, only to have their work derided by an influencer who presents their contradictory opinion as fact. When presented with information or data from scientific studies that contradict their beliefs, people are more likely to ignore the evidence and double down on what they think they know.

“We see that playing out with athletes all the time,” Tiller said. “If you try and challenge somebody’s belief about low-carbohydrate diets, and if they really believe that it works, no number of facts and figures, no amount of data to the contrary is going to change their mind. It just makes the problem worse.”

Science is often seen as closed off and elitist, their journal articles behind a paywall and loaded with dry, technical jargon. Most people will instead gravitate toward easily-digestible sources of information. In a battle for your eyeballs, an influencer will easily win. This is how pseudoscience and bad advice spreads; a 2018 study by MIT researchers found that false news spreads much more rapidly on Twitter than real news does. For years, scientists trusted the facts would eventually win out. Now it’s becoming clear that won’t happen organically, and researchers are changing their strategy.

“What I’m trying to do now as a scientist, as a critical thinker, and as an athlete, is to try and frame the health and fitness industry through that lens of scientific skepticism,” says Tiller. “To teach people to engage in formal critical thinking – promoting not ‘what’ to think, but ‘how’ to think. Rather than constantly looking for the next quick fix or the next shortcut, people need to stop and ask questions about what they’re hearing and who they’re hearing it from.”

Tiller uses the example of flying in an airplane as one way to grasp the concept. If you’re on a flight, you implicitly trust the pilot has expertise to fly the plane. After all, pilots have to undergo thousands of hours of supervised training in order to fly for a major airline. If a random passenger stands up mid-flight and announces they could get you to your destination in half the time, would you blindly trust them to take over in the cockpit? Probably not. That’s skepticism, and should be our default setting when we hear things that sound too good to be true.

“When it comes to abstract things like fitness or nutrition, everybody’s so quick to question the experts, and everybody thinks they know better,” Tiller said. “But when the stakes are high enough, people get very real, very quickly, and they have respect for the experts.”

Your guide to critical thinking

When faced with a product, service, or advice that promises something extraordinary—whether better performance, faster recovery, easy weight loss, or the secret to better health—it’s natural to be intrigued. But intrigue should also trigger skepticism. That doesn’t mean all products are shams or every expert is a modern-day Harold Hill, but at the very least, it’s a good idea to confirm they’re not before you buy what they’re selling. As the old science maxim goes: Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

“You don’t have to be a scientist to be a critical thinker,” Tiller said. “You don’t have to know anything about physiology. You just need to ask questions to determine if something is legitimate, instead of taking advice or endorsements at face value.”

Tiller recommends athletes ask three essential questions:

- Is this person a legitimate expert? Look for training, certifications,experience and affiliations with professional organizations that require ongoing education. Judge the advice they give on merit. Does it stand up to scrutiny?

- What does this person have to gain? If a professional athlete endorses a product, that doesn’t necessarily mean they use that product. It could simply mean they’re paid to use their platform to endorse it.

- Does this work through an actual mechanism of the body, or is the effect psychological? Investigate the plausibility of the claims made. Does the body actually operate in this way?

Sullivan adds that when searching, don’t simply click on the first option that pops up in Google. Instead, seek out reputable sources of information. Anyone can post on the internet, but certain publications and organizations are required to undergo a vetting process known as a peer review, where widely acknowledged experts in a field reviews content for accuracy and clarity before publishing. Seek out information from scientists, faculty, and established experts in sports over bloggers and influencers. Many people are surprised to learn that most researchers are quite accessible, and will usually provide a free copy of their paywalled journal articles upon request. They love talking about their work (most sport scientists are athletes themselves), and many will respond to simple queries via email.

“Make it a deliberate practice to look for more information,” Sullivan said. “Don’t just go buy things that look good, believe things you hear. Those are gut feelings. Find the evidence. You’ll be a better athlete if you do.”