The 31 Most Important Races in Triathlon History

(Photo: Triathlete)

Table of Contents

When people talk about the most important races in triathlon history, they’re likely to bring up individual performances: Julie Moss crawling across the finish line in Kona, for example, or the Iron War. Maybe they’ll even talk about the time Gwensanity swept the Rio Olympics, or one of the many amazing sprint finishes in tri history (which mostly seem to involve Lionel Sanders these days).

But all of these individual events lose sight of the bigger picture: the races themselves. Without them, we wouldn’t have the stage to witness these incredible performances. Triathlon has come a long way from its humble origins in San Diego to the thousands-strong extravaganzas that take over entire cities to swim, bike, and run. How did we get from there to here? Let’s take a walk through the most important races in triathlon history.

In the beginning

1974: Triathlon is born

When Jack Johnstone and Dan Shanahan created a new race for the San Diego Track Club, they weren’t thinking about creating an entirely new sport. They just thought it’d be a fun way to spice up their local race scene. Forty-six people paid the one-dollar entry fee for the Mission Bay Triathlon, which consisted of a total of six running miles, five cycling miles, and 500 yards of swimming (in that order). It was weird and complicated and also a whole lot of fun. Half a century later, the sport only vaguely resembles that first race, but one thing remains the same: When you string swim, bike, and run together in one event, it’s a blast.

RELATED: Recalled: The Invention of Triathlon

1978: An epic challenge in Hawaii

One day, on the Hawaiian island of Oahu, Judy and John Collins dreamed up an epic endurance challenge: Could anyone take on three of the toughest endurance races in Hawaii back-to-back-to-back? The pair sketched out the logistics of what they called the “Iron Man” race: the 2.4-mile Waikiki Roughwater Swim, 112 miles of the Around O’ahu Bike Race, and the 26.2-mile Honolulu Marathon. It had never been done before, and it sounded hard – really hard. But 18 athletes looked at the invitation and said they’d give it a go. Twelve crossed the finish line that day, cementing their status as legends in a race that would become synonymous with the word “endurance.”

RELATED: How Long is Ironman? A Look at How the Ironman Distance Came to Be

1981: Ironman moves to Kona

News of the new Ironman triathlon traveled fast. In 1979, Sports Illustrated wrote an article about the small group of crazies taking on an epic endurance challenge in Hawaii, and attendance exploded to over 100 entrants for the 1980 race. That event was covered by ABC’s Wide World of Sports, inspiring even more people to inquire about entering the event. To accommodate the larger field, the race moved from the tranquil shores of Waikiki to the village of Kona on the Big Island of Hawaii. For more on that first-ever Ironman, check outThe Origins of Ironman: How Kona Became Kona.

1981: A successful Escape From Alcatraz

After competing in the Hawaii Ironman race in 1979, triathlete Joe Oakes was looking for a new – yet equally as epic – challenge. Taking inspiration from the original Iron Man, Oakes strung together two popular races in his hometown of San Francisco – the swim from Alcatraz Island and the Double Dipsea run over Mount Tamalpais – with a bike ride over the Golden Gate Bridge. He recruited the local athletic club to help him put on the first-ever Escape From Alcatraz Triathlon. It was a hard race – and also a massive hit. The Dolphin Club still puts on the original Escape From Alcatraz race each year for members only, but a second, commercially-produced race proves just as popular, drawing more than 2,000 triathletes to San Francisco each year.

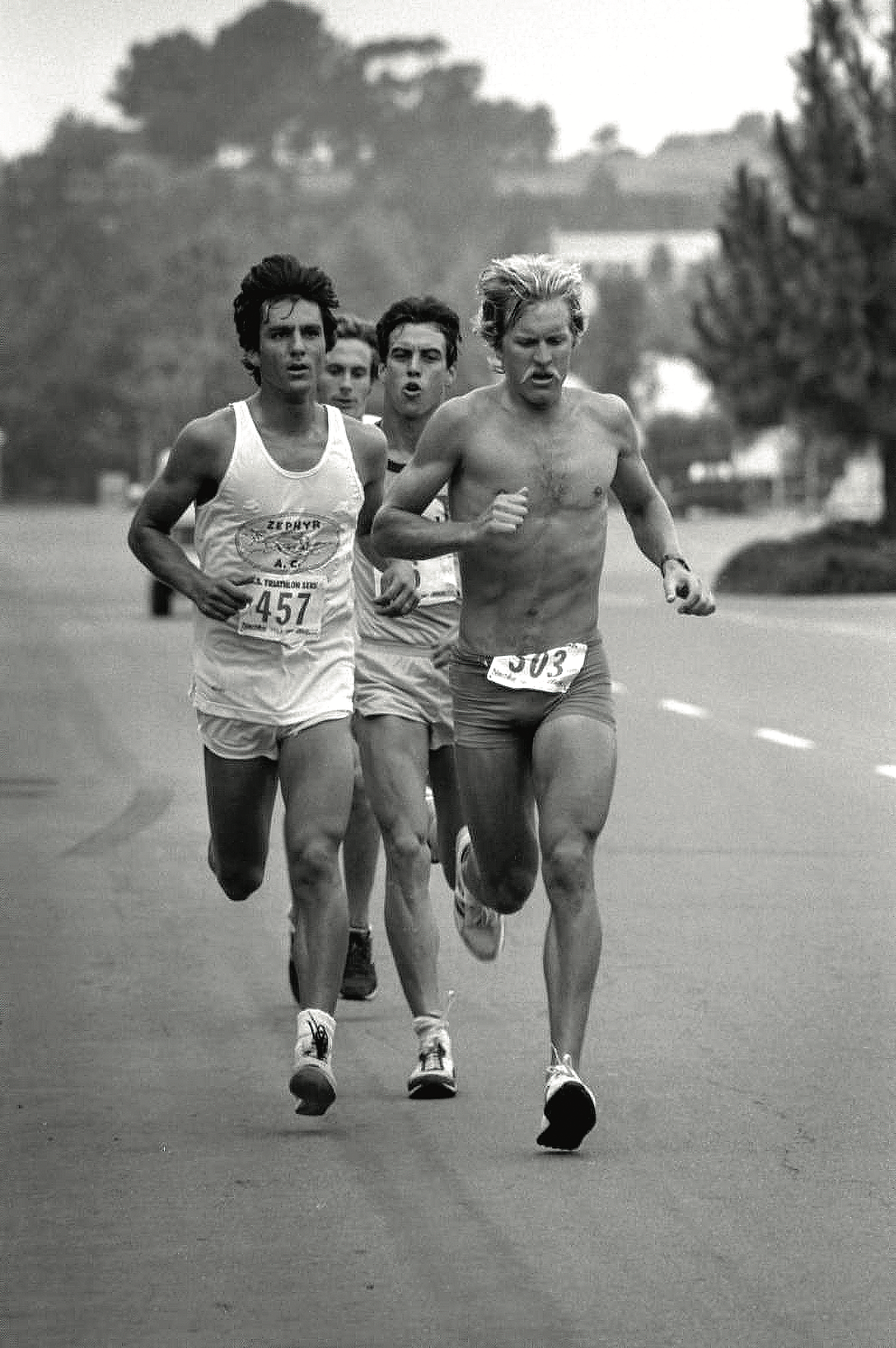

1982: Triathlon goes pro

Torrey Pines State Beach in San Diego was the site of the first-ever professional triathlon, which boasted a prize purse of $1,600. And what a field it was: In addition to featuring a rematch of Moss and Kathleen McCartney (who passed Moss in the finishing chute after her infamous collapse), the race saw the debut of triathlon’s “Big Four” of Dave Scott, Scott Molina, Scott Tinley, and Mark Allen, who would rule the sport for the next 14 years. Originally conceived by founder Jim Curl as a 2-kilometer swim, 35-kilometer ride, and 15-kilometer run, the race eventually shifted to what is now known as the Olympic distance: 1.5K swim, 40K bike ride, and 10K run. The new U.S. Triathlon Series, or USTS, would go on to produce 120 events in 30 cities across the country, paying out more than $1 million in prize money until its end in 1993. (Want more pro triathlon history? Check out Looking Back at 40 Years of Professional Triathlon.)

Growing up (and growing pains)

1982: Triathlon goes to Nice

Wanting to capitalize on the popularity of the Ironman broadcast, International Management Group proposed a world-class triathlon in a world-class location with world-class competition – and what better world-class location than Monaco? Plans were laid for a glitzy, glamorous broadcast, but two months before the event was to take place, Princess Grace of Monaco died in a horrific car crash. A one-year period of mourning was enacted, banning all celebratory events, including the planned triathlon. IMG needed to immediately find a new home for its race. Nice stepped in, and the change proved fortuitous: The Nice Triathlon became the place to race, attracting Ironman champions and ITU champions alike to take on the unique middle-distance course. Mark Allen wrote about his experience in Nice here.

1982: Tri gets the Hollywood treatment

Capitalizing on the surging popularity of triathlon, California-based race promoter Hans Albrecht presented CBS with a plan for a made-for-TV race at Zuma Beach in Malibu. Billed as the “U.S. Pro Championships,” the race boasted a largest-ever $17,000 prize purse. As it turned out, those who won money that day earned every cent. The race was described as “a nightmare” for the best triathletes in the world: Mark Allen nearly drowned in the frigid waters, and many more struggled with hypothermia. A chaotic bike on the Pacific Coast Highway, which remained open to traffic, caused Scott Tinley to crash and break his collarbone. Still, the Malibu race cemented triathlon as a viable platform for advertisers and investors, who poured money into the sport, ensuring its long-term success. The Malibu Triathlon continues to this day, although its recent history has been rocky.

1983: Triathletes find their community at Wildflower

Though some triathletes traveled to iconic races like Kona or Nice, most stayed local – the concept of “race-cation” simply wasn’t a big thing in the 1980s. That is, until the Wildflower Triathlon. The Central California event wasn’t just a race, it was a weekend, with athletes encouraged to camp on the race and share the love of swim-bike-run with their fellow triathletes. Though the Olympic- and half-distance race itself was grueling, sharing a beer with triathletes around a campfire after more than made up for it. Wildflower quickly gained a reputation as “The Woodstock of Tri” for its fun, free-spirited nature, attracting more than 7,500 athletes and 30,000 spectators each year in the early 2000s. However, a string of challenges, including climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic, has thwarted race production in recent years.

1983: From Liberty to Liberty

How do you celebrate the birth of a nation? In 1983, a 100-mile triathlon was one option. On the Fourth of July that year, 13 American triathletes stood at the base of the Statue of Liberty, listening to the final notes of the “Star Spangled Banner” before diving into the Hudson River. From there, they swam, biked, and ran their way to the Liberty Bell in downtown Philadelphia. The idea was a crazy one, but just crazy enough to capture the attention of America – the following year, the competitive field grew to more than 150. Though the race died off by the late 1980s, it has seen a few revivals over the years, including its 20th anniversary in 2003, then again in 2007 and 2009.

1984: Celebs give it a tri (and get scammed)

Though the Malibu Triathlon eventually became known for drawing a big field of Hollywood celebrities (including Robin Williams, Jennifer Lopez, and Matthew McConaughey), it wasn’t the first race with star power. That distinction belongs to the Bahamas Diamond Triathlon of the Stars, an event designed by San Francisco diamond broker Bruce Portner. The event was extravagant to the max, with over 40 celebrities from TV, film, and sport invited to take part in the race (notable names include Lynda Carter of Wonder Woman, Linda Blair of The Exorcist and movie star Billy Dee Williams). USTS founder Jim Curl was recruited to organize a concurrent race for the top pro triathletes, who competed for an unusual prize purse of $100,000 in diamonds. But the glitz and glamor turned out to be a facade: Some of the diamonds turned out to be low-quality or entirely fake, and Curl was arrested and jailed.

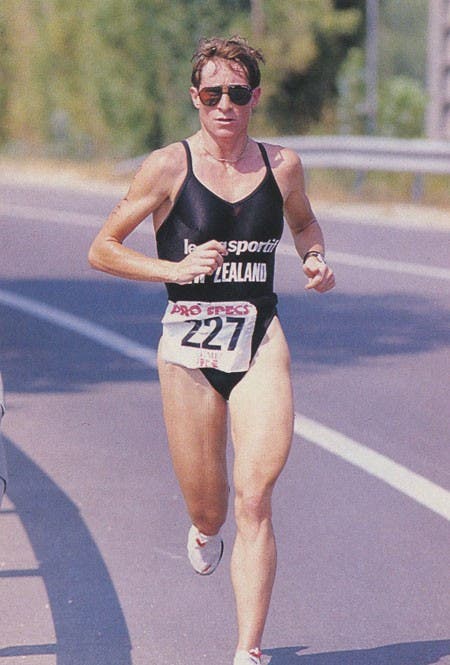

1989: A global phenomenon

Just 15 years after its birth, tri officially went worldwide. The very first International Triathlon (ITU) World Championship collected 800 of the world’s best pro and age-group triathletes from 40 countries for a race in Avignon, France. The event was designed to lay the foundation for legitimizing triathlon as an Olympic sport, a process that would take 11 years to complete.

The race also proved to be a pivotal moment for gender equality. When New Zealand pro Erin Baker discovered the men’s prize purse in Avignon was larger than the women’s, she began campaigning for parity. The male athletes joined in, refusing to race unless the prize purse was distributed equally. The campaign was successful, and (then-rare) equal pay has since been the standard in the sport ever since.

The big show

1990: Women take center stage

Though triathlon achieved gender parity in pro prize purses in 1989, equal participation has always been a challenge. By 1990, women only made up 25% of total triathletes in the United States, and USA Triathlon set out to change that. They recruited Judy Flannery, an accomplished age-group triathlete, to head up the organization’s first-ever women’s commission, which led to the development of the Danskin Triathlon Series. The women-only races, gave pros like Michellie Jones, Paula Newby-Fraser, and Sally Edwards a spotlight and platform to inspire age-groupers to give tri a try, and it was successful: Participation grew from 150 women at its inaugural event in Long Beach to over 20,000 across the U.S. each year. The Danskin Triathlon Series spurred more women-only race series’, including SheRox and IronGirl. USA Triathlon continues to make women’s participation a priority today.

1991: Powerman brings the power

A variety of races have and continue to be developed under the umbrella of “multisport.” Though triathlon remains the most popular, duathlon has steadily held second place, thanks in part to the Powerman Duathlon in Zofingen, Switzerland. The race, which was founded in 1989, showcased a 2.5K swim, 120K bike, and 30.5K run. The swim-lite race ran under the radar of most pro triathletes until 1991, when they learned about the massive prize purse offered. At $200,000, Powerman was paying more than Ironman Hawaii. This kicked off an annual wetsuit-less exodus to Switzerland. Scott Molina and Paula Newby-Fraser took home the money in 1991, with other notable names, including Mike Pigg, Mark Allen, Erin Baker, and Natascha Badmann following suit.

1996: XTERRA invented

In the mid-90s, a group of mountain bikers in Maui were washing their bikes after a day in the dirt when one of them remarked to Dave Nicholas, “They’re down there swimming around. We could put on one of those Ironman things, but instead of road bikes we could do it on mountain bikes.” The idea stuck – first called AquaTerra, the event combining swimming, mountain biking, and trail running grew a loyal following. Take an (off-road) trip back in time with our history of the race: When XTERRA Triathlon Got its Start.

2000: Finally, the Olympics

In 1994, only five years after the International Triathlon Union (ITU) was founded in Avignon, triathlon was approved as an Olympic sport by the International Olympic Committee. Olympic triathlon, with a 1.5K swim, 40K bike portion, and 10K, made its official debut at the Sydney Games. Simon Whitfield and Brigitte McMahon took the gold medals in the men’s and women’s events, respectively.

Branching out

2002: Battle of the sexes

Who makes better triathletes – men or women? The question was answered in a battle of the sexes in Minneapolis, where pro women started ahead of the pro men by 9 minutes and 39 seconds in a race roughly three-quarters the length of an Olympic-distance triathlon. In a dramatic race, Barb Lindquist beat everyone – male and female – to take home the $50,000 prize. She did it again the following year, where the prize was upped to $250,000 and the competitive field even deeper. But Lundquist later asserted the real prize was showing “women can go out and kick butt, race tough and with integrity.”

2002: Challenge Roth goes independent

When the Franconian Triathlon was established by Kona triathlete Detlef Kühnel in 1984, the German host city of Roth turned out in a big way to support the athletes competing. The race’s reputation as a raucous party made it a popular event for triathletes in Europe and beyond, and Ironman came calling in 1988. Under new management, Ironman Europe event brought triathletes from around the world to Roth, but disagreements over the organization and finances of the race caused behind-the-scenes drama that began to overshadow the race itself. In 2002, Roth broke from WTC, setting the template for success without the Ironman brand. The race – now Challenge Roth – hasn’t lost its luster. Today, it’s the largest iron-distance race in the world, selling out in mere seconds each year as triathletes clamor to join the party in Germany.

2003: Norseman dials up the extreme factor

When 21 individuals jumped into the frigid waters of Eidfjord in Norway, they had no idea they were part of what would one day become an ultimate bucket-list event for triathletes. The Norseman Triathlon, with its cold swim, mountainous bike, and trail run up the side of a mountain, took the iron distance to a whole new – and yes, extreme – level. Today, what used to be a handful of crazies in Scandinavia is a full-on category of racing around the world known as “extreme triathlon,” of which Norseman is king. The OG race is so popular, thousands of people from all over the world enter XTRI qualifying races and apply for the lottery each year in hopes of snagging one of 250 spots on the starting line.

2005: 70.3 is born

With demand for long-course racing at an all-time high, Ironman CEO Ben Fertec began looking for ways to give triathletes the opportunity to race more often. His solution: the 70.3, or half the distance of a full Ironman. The 1.2-mile swim, 56-mile bike, and 13.1-mile run presented athletes with the opportunity to go long without needing to recover for months. The distance made its debut in England, and though initial participants mostly used it as a stepping stone to the full distance, it soon found its footing as a standalone goal. Today, the half distance is more popular than its full counterpart, with 104 Ironman 70.3 races on offer in 2025 – not to mention countless independent events of a similar distance.

Exciting and new

2007: HyVee cashes in

Triathlon had its share of big-name sponsors over the years – Bud Light, Toyota, Ford, and Life Time Fitness were early funders of the sport – but it was a regional grocer who would make the biggest investment. The first edition of the Hy-Vee Triathlon, held in downtown Des Moines, Iowa, featured the largest prize in triathlon to date, with $200,000 each for the men’s and women’s elite winners. The big money garnered big interest, with approximately 10,000 spectators descending on the Iowa state capitol to cheer on the pro field. The prize purse grew even larger over the years, topping out at $1.1 million before the event was discontinued in 2014.

2009: Rev3 shakes things up

Inspired in part by the success of the Hy-Vee Triathlon, race organizer Charlie Patten decided to take on Ironman by creating a new half-distance race with a prize purse $10,000 larger than what was offered at the Ironman 70.3 World Championship. But that wasn’t all: The newly-planned series, known as Revolution3 (or Rev3 for short) would also offer up $20,000 in cash and prizes to age-groupers. A star-studded field turned out for the inaugural event in Connecticut (including 70.3 world champions Mirinda Carfrae and Joanna Zeiger, ITU World Champion Paul Amey, and Olympian Matt Reed) and many pros made stops on the Rev3 circuit of half- and Olympic-distance events in the following years. The race series enjoyed a brief period of popularity (and a few years of eye-popping prize purses), but the model proved unsustainable: In 2014, Rev3 discontinued its pro prize purse, and ten years after its launch, Ironman acquired Rev3’s most popular age-group races in Connecticut, Virginia, and Maine.

2013: Super Sprint Vegas

If you’re going to put on a race in Las Vegas, you’ve got to go big – and former pro triathlete Marc Lees did exactly that with his Grand Prix super-sprint event. Under the dazzling lights of the famous Las Vegas Strip, Lees erected a 115,000-gallon swimming pool in a parking lot across from the Las Vegas Convention Center, where the world’s fastest triathletes dove in for two circuits of a 300-meter pool swim, 8-kilometer draft-legal bike, and a 2.5-kilometer run. At the time, it was a novel event – but today, we see it in many forms, including Super League Triathlon and the triathlon mixed relay, which became an official Olympic sport at the 2021 Games. As it turns out, what happens in Vegas doesn’t always stay in Vegas.

2016: Paratriathlon joins the Paralympics

Though athletes with physical disabilities had been competing in triathlon since the 1980s, the sport of paratriathlon was not formalized until 1996, when the International Triathlon Union (ITU) staged its first official World Championships for paratriathletes. In 2010, Olympic triathletes joined their paratriathlon counterparts in campaigning hard for triathlon to be included in the Paralympics, and the request was approved for the 2016 Games in Rio. Team USA, led by the podium sweep in the PT2 category of Alyssa Seely, Hailey Danisewicz, and Melissa Stockwell, took home a total of two golds, one silver, and one bronze. Up next: adding the mixed relay to the Paralympic program.

2019: World’s first virtual triathlon

The “virtual” triathlon format – in which participants swim, bike, and run in their own neighborhoods and record the results, was originally designed to bring new athletes into the sport and help veteran athletes stay motivated through the winter offseason. When USA Triathlon announced the new format in October of 2019, it was mostly dismissed. But only two months later, a cluster of patients in China’s Hubei Province began to experience the symptoms of an atypical pneumonia-like illness that would give rise to a global COVID-19 pandemic, shuttering races and making the virtual triathlon format a go-to for more than a year.

The era of speed

2020: Super League Arena Games

After a decade of watching short-course race opportunities for pros dwindle, age-group triathlete Michael D’Hulst and two-time Ironman World Champion Chris “Macca” McCormack decided to shake things up with a new and exciting format. Borrowing ideas from popular events in triathlon history, including the Grand Prix super-sprint event, Super League Triathlon was launched with a test event on Hamilton Island, Australia. There, the founders tinkered with race formats and high-tech live broadcasting options – both elements that would prove to be central to the brand. The Super League Championship, a sprint-distance gauntlet held at locations around the world, revitalized interest in pro short-course racing, but its biggest innovation launched during COVID lockdowns of 2020: the Super League Arena Games, a fast-paced indoor triathlon that combined in-person and virtual elements of racing. In 2022, the Arena Games (under Super League’s rebranding, Supertri) joined forces with World Triathlon to become the first-ever Esports Triathlon World Championship.

2020: Deep PTO pockets create the largest prize purse in triathlon history

The largest prize purse in the history of the sport does not come from the largest race or even the largest series in the sport. Instead, it came out of a small event in Florida that ponied up $1.15 million – more than twice the amount distributed at the Ironman World Championship and just barely breaking the record set by the Hy-Vee Triathlon in 2012. The mega prize purse, designed to bring pros to Daytona for the first-ever PTO World Championship, was a joint effort between Challenge Family and the Professional Triathletes Organization. Paula Findlay and Gustav Iden took top honors and a $100,000 paycheck for their wins; the rest of the funds were paid out in decreasing amounts to the top 60 finishers in the men’s and women’s fields.

2021: Mixed Relay Olympic debut

The 2020 Summer Olympics, held in 2021 after COVID pandemic delays, saw the debut of the triathlon mixed relay. Born of the super-sprint format over a decade prior, the mixed team event featured teams of two women and two men, each performing a 300-meter swim, 6.8K bike, and 2K run before tagging the next athlete. It was a thrilling race to watch, with Great Britain’s Jess Learmonth, Jonny Brownlee, Georgia Taylor-Brown, and Alex Yee edging out Team USA and Team France to the first-ever Olympic gold medal in the event.

2021: Collins Cup merges short- and long course racing, sparks T100 tour

The concept of team triathlon grew with the PTO’s Collins Cup, named for Ironman founders John and Judy Collins. Inspired by golf’s Ryder Cup, the race pitted three teams (USA, Europe, and Internationals) of twelve athletes each in head-to-head-to-head matches in a bid to win points. In addition to bringing together 36 of the world’s best short- and long-course triathletes together in one not-quite-middle-distance race (a 2K swim, 80K bike, 18K run known as the “PTO distance” that later gave rise to the T100 Tour), the race also recruited legends of triathlon to serve as captains, or coaches. Team Europe won the inaugural event, then followed it up with a second win in 2022.

2021: First non-Hawaii Ironman World Championship

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, most triathletes could never have imagined an Ironman World Championship anywhere other than its longstanding home in Hawaii. But as the pandemic raged on, forcing a cancelation of the race in 2020 event and a postponement in 2021, Ironman began to look elsewhere – specifically, St. George, Utah, which had stepped in at the last minute to host the 70.3 World Championships after travel restrictions forced a move from New Zealand. The move proved to be more than a temporary fix, however; later, it would be revealed the event was a test balloon of sorts to determine the feasibility of a non-Kona world championship in the future.

2022: Sub 7/Sub 8 shatters records

Just how quickly can a triathlete cover 140.6 miles? That was the question posited by the Sub7/Sub8 Project, a carefully-designed science experiment based on running’s Breaking2 marathon project. Four of the top pros in the sport – Kristian Blummenfelt, Joe Skipper, Nicola Spirig, and Kat Matthews used every advantage at their disposal to shave off every second possible in an iron-distance effort: pacers, drafting, flat conditions, days selected for optimal weather, custom-made equipment, and a support crew that did everything from reporting splits to personally misting the athletes with water as they ran. It was a spectacle, to be sure, but also an inspiring test of speed and endurance. The answer, by the way: 6:44 and 7:31, set by Blummenfelt and Matthews, respectively.

2022: Separate IMWC champs for men & women

After three years away from the Big Island, the Ironman World Championship returned with a backlog of entries. To accommodate the larger field, Ironman split racing into two days: One for pro men and the majority of the age-group male field, and one for pro women, age-group women, and the remaining age-group men. Though the 70.3 World Championships had utilized this two-day format since 2017, the Hawaii event had continued to have all athletes race on the same day at the same time.

The two-day format was widely praised for creating more opportunities for women, cleaner races, and better coverage of both events. But keeping the two-day format ultimately came at a cost: Ironman announced that due to local logistical challenges in securing Kona for another two-day event, the men’s and women’s world championship races would also be held in two different locations going forward. In 2023, the women’s world championship race was held in Kona, while the men’s event traveled to Nice, France. They switched in 2024, and Ironman has confirmed the two-day format will continue in 2025, with women in Kona and men in Nice.