Supportive Science: The Quest to Build A Better Sports Bra

(Photo: University of Portsmouth Research Group in Breast Health)

In the archives of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, tucked in between a collection of items documenting the discovery of modern orthodontia and original scripts from the television show M*A*S*H, is a simple garment made of white cloth with an elastic band underneath. By today’s standards, this particular design would be recognized as athleisure, worn at home, while running errands, or maybe under a billowy tank top for a brunch date. But in 1977, it was an innovation that changed running forever.

From jockstrap to Jogbra

The invention of the sports bra is a quintessentially American story, born of necessity, ingenuity, and a few happy accidents. Shortly after the 1972 Title IX legislation mandated equal opportunity for girls and women in sports, a new fitness craze called jogging took the United States by storm. Running became a mainstream activity, with an estimated 25 million Americans taking to their streets, paths, and track ovals. A full industry sprung up to cater to the needs of these joggers, from Bill Bowerman’s iconic waffle-machine running shoes to the mass production of polyester running shorts and terry-cloth headbands.

But almost all of these innovations were created by men, for men. Despite the surge in female athletic participation in the 1970s, no one was really thinking about the needs of women in sport—specifically, the need for a supportive garment to help reduce breast movement as women ran. Brassieres were mostly regarded as a fashion item designed to enhance cleavage, not a functional one for anatomical support. The jockstrap, invented in 1874, was well-established as an essential piece of equipment for men to reduce bouncing of their genitalia during sports, yet no one had ever thought to make a female equivalent for athletic women.

New runner Lisa Lindhal was lamenting this very fact to her sister, Victoria Woodrow, when her husband cracked a joke: “Why not wear a jockstrap, then?” For extra comic effect, he slipped his own jockstrap over his head, wiggling and writhing until the garment awkwardly covered one side of his chest. The antics made Lindhal double over with laughter, then suddenly stop. Lindhal looked at her husband with a raised eyebrow: Wait a second. Could it be…?

The jockstrap looked like it could work, especially after Lindahl took it from her husband, pulled it over her own head, and pulled the pouch down over her own breast like the cup of a brassiere. Though Lindhal didn’t know much about garment construction, two of her running friends did: Hinda Miller and Polly Smith, who worked as costume designers. Together, they excitedly developed a prototype from two jockstraps stitched together to provide breast support. They tested their invention with a jog around the block: Lindhal wearing the bra, Miller running backwards a few feet in front of her to see if there was any change to the motion of the breasts. It seemed to work.

Lindhal, Miller, and Smith thought they had developed a clever solution to a personal problem. They had no idea that their invention, which they named the Jogbra, would soon become a revolution in athletic wear. They had no idea they would enable widespread female participation in sports. They didn’t see their product evolving into a retail market amounting to approximately 14 billion dollars worldwide each year. And they certainly didn’t think their invention would ever be enshrined in the world’s largest museum, and widely regarded as one of the most important inventions in athletics.

“The invention of the Jogbra changed the game forever,” says Laura Havel of the Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation. “[It] represented a revolution in ready-to-wear clothing, enabled women’s participation in athletic activities, and advanced women’s health and well-being.”

The sports bra’s evolution (or lack thereof)

If you hold up a sports bra made in the year 2020, it will have much of the same basic architecture of the original Jogbra: an elastic band around the ribcage, straps that cross in the back (known as a “racerback” style), and a compressive design that guides both breasts toward the center of the ribcage. Fabrics and features have changed, adornments have been added, and construction styles have been made more efficient for mass production, but if you hold up the modern sports bra, you can see its heritage, like a young child who bears a striking resemblance to her great-grandmother.

Is it a testament to the thoughtfulness and intelligence of the inventors, or a lack of evolution? Experts say it’s a little bit of both. After the Jogbra’s invention, the sports bra was quickly in demand by active women, causing numerous lingerie companies, including Vanity Fair and Olga by Warner’s, to rush into the sports bra market. Most simply copied the design of the Jogbra to meet consumer demand; as a novel concept, the sports bra was already better than the alternative (a flimsy fashion bra, or worse, nothing at all) so there wasn’t much demand for improvement.

But there was also a lack of science to suggest a better way. Unlike running shoes, which quickly got an infusion of cash for research and development, scientific studies of sports bras didn’t begin until 1984, when Utah State University student LaJean Lawson used a movie camera rented from Hollywood to record and analyze the breast movement of 60 different women while running. By scrutinizing 16-millimeter film, shot at a rate of 100 frames per second, Lawson was able to ascertain how sports bras performed across various bra cup sizes. Her research was the first to discover that a one-size-fits-all approach to the garment doesn’t work. The way sports bras are usually designed—for competitive athletes who typically have smaller chests—are less effective at controlling the breast movement of the average woman.

Despite breaking into a new realm of research, Lawson’s study was widely panned by government watchdogs—not because of shoddy methodology, but because it was considered a waste of taxpayer dollars to study breasts. Puritanical politics got in the way of progress.

Meanwhile, the sports bra market exploded as women sought out support for their active pursuits. Unlike the late 1970s, it’s not difficult to find a sports bra these days; in fact, it’s easier than ever, thanks to an athleisure trend which makes sportswear high fashion. But finding a good sports bra is an entirely different story. Although sports bras are supposed to support and protect the breasts during vigorous activity, most selections on the market today do neither. Gather any group of women who run, and the topic of sports bras will likely elicit a cacophony of frustrated groans about shoulder pain, nipple chafing, lack of motion control, and underwires that poke. Some might even show you scars on their ribcage or underarm, accumulated from years of wearing sports bras that rub some of their most delicate skin areas raw. For some women, wearing a bad sports bra is only marginally better than not wearing one at all.

Lawson’s study was only the tip of the iceberg in understanding just how important sports bras can be for female athletes. It took almost 20 years for the science of sports bras to return to the laboratory. Now, more than 40 years after two jockstraps were stitched together, researchers are finally starting to understand how to build a better sports bra.

The bounce test

Almost every woman is familiar with “The Bounce Test,” a wholly unscientific method for finding a sports bra involving a series of awkward hops, skips, and running in place while in the confines of a dressing room. The motions must be done vigorously, to see if the bra really does control motion, but not so vigorously it draws the notice of the retail clerk (who probably knows exactly what’s happening behind the curtain).

It’s the same eyeball test the inventors of the Jogbra used, and the scientific method Lawton used, but with video cameras. For years, observation was the only method used to test sports bras. But within the confines of the University of Portsmouth Exercise Science Lab, the tests have become exponentially more high tech.

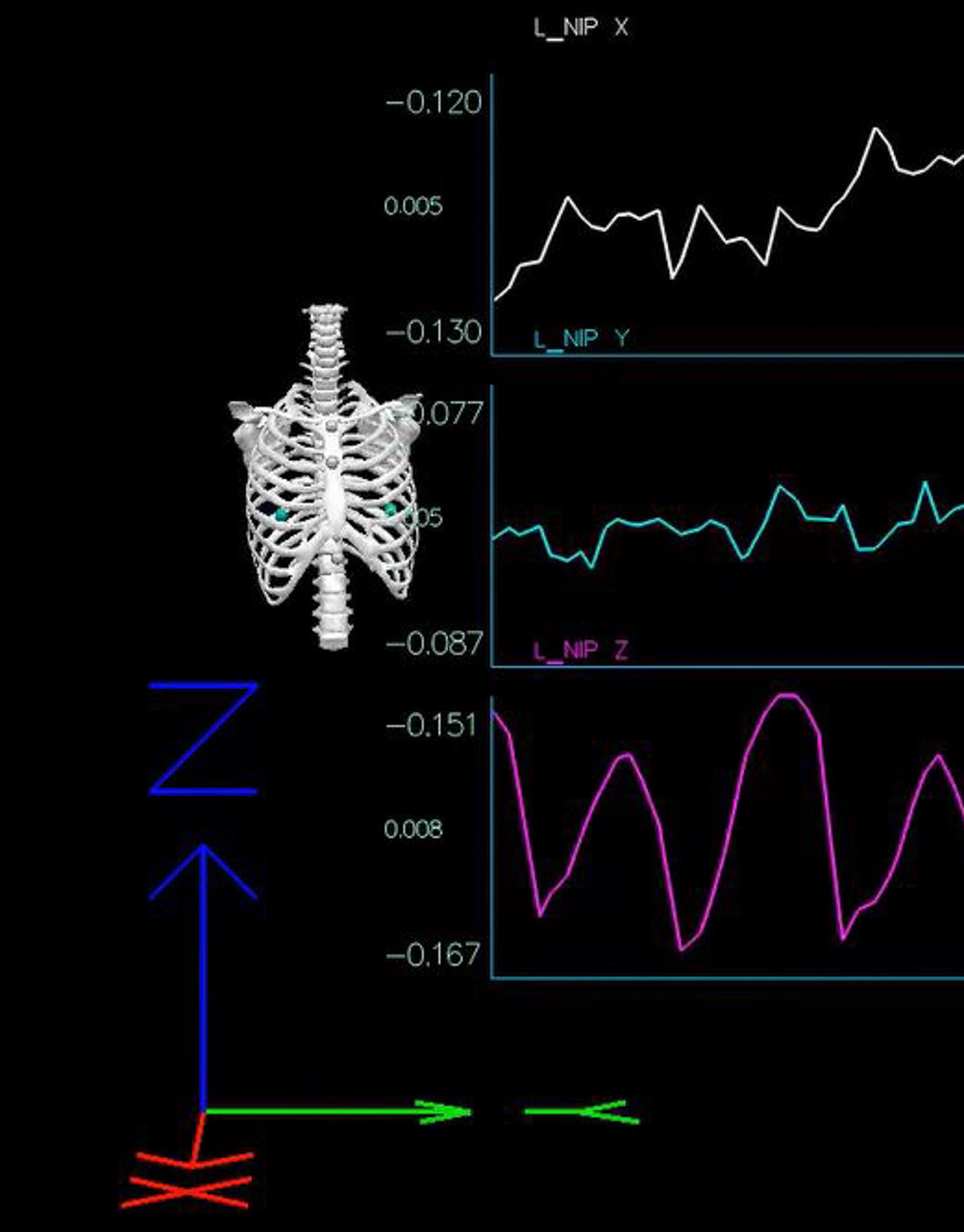

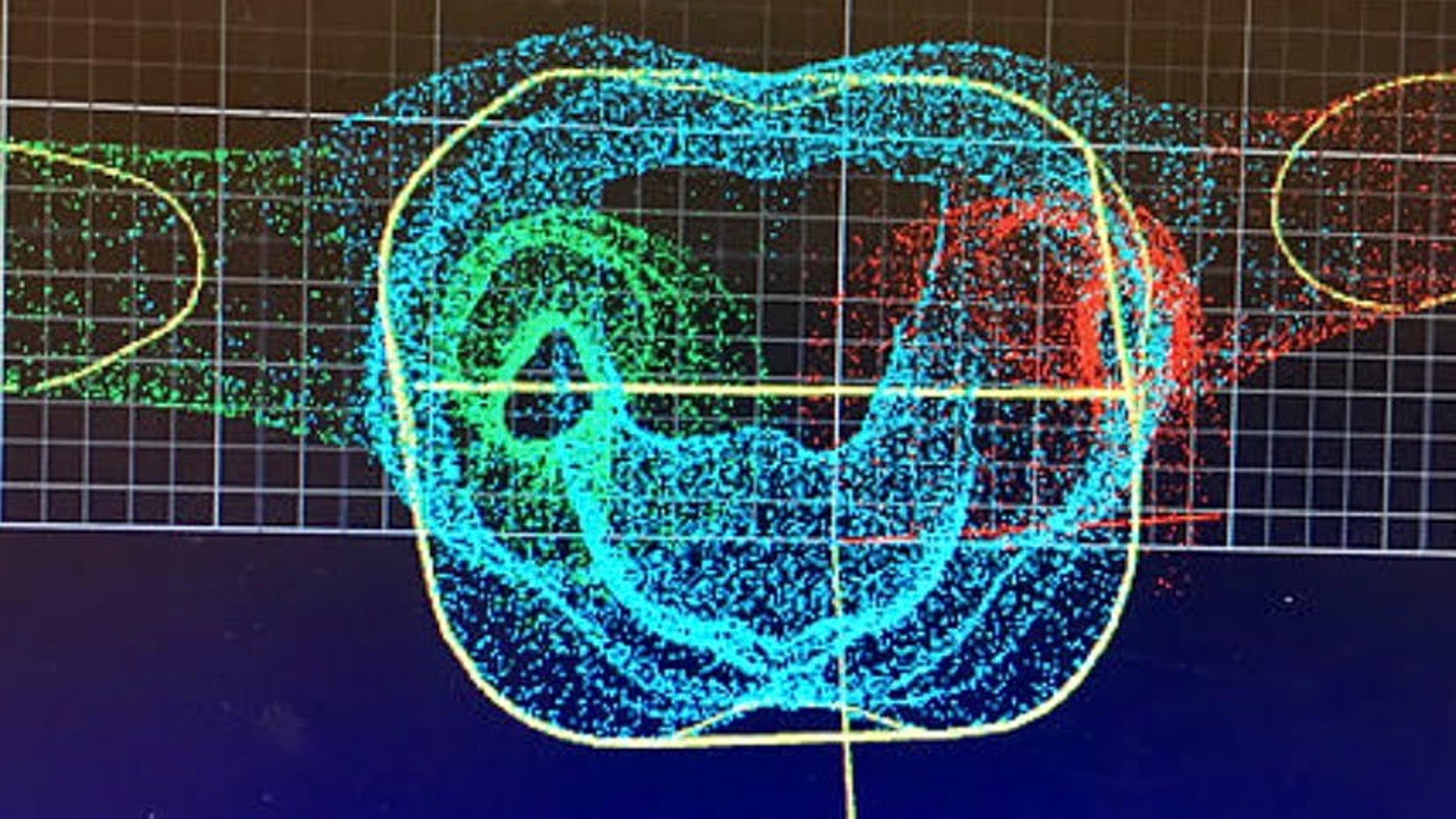

In one corner of the lab, a video camera points at the chest of a woman running on a nearby treadmill. A grid of silver dots adorn the outside of her sports bra, allowing for 3D motion tracking of the breast; stick-on sensors also affix to the skin inside of the bra for the same purpose. Electromyography sensors are placed on the chest and shoulders to measure changes in muscle activity in response to the sports bra. A force platform measures ground reaction forces while running, while a 3D scanner produces a high-resolution image of breast volume and shape. A thermal imaging camera tracks the transfer of heat from the body through the bra—an especially handy tool in the lab’s extreme environment setup, which allows for the creation of any environmental condition, be it New Orleans humidity or dry Death Valley heat.

This is the Research Group in Breast Health, where a team of 12 researchers have conducted and published more than half of all scientific studies on breast biomechanics worldwide. It’s the first research group to devote itself solely to the structure, function, and motion of the breast—an area of the body that, despite being present on half of the world’s population, was grossly underrepresented in scientific literature for years.

Dr. Joanna Wakefield-Scurr discovered this lack of information in 2005, when she visited her medical professional to diagnose her breast pain and tenderness. At first, her doctor assumed it was linked to her menstrual cycle—hormone fluctuations can cause a woman’s breasts to feel swollen and painful—but when Wakefield-Scurr tracked her symptoms and her cycle to test this theory, a different pattern emerged. Instead of aligning with her hormones, her breast pain was directly linked to the days she went running.

The advice Wakefield-Scurr was given was to “go and find yourself a good bra.” When she went to a department store and tried on a few brands, she read the claims of support and motion control each bra made on its packaging. The scientist in her started wondering—was there any evidence behind this stuff? Wakefield-Scurr, a PhD researcher studying the biomechanics of hockey players, couldn’t recall ever seeing a study on breast movement in sports. When she dug through the archives, her suspicions were confirmed—aside from Lawson’s 1984 research and a smattering of other small studies, there wasn’t much out there.

“You know, when you looked at something like footwear or trainers, there’s absolutely thousands of published papers in that area,” says Wakefield-Scurr. “But nothing on breasts and bras. I knew I couldn’t be the only one having exercise-related breast pain or wanting to know what makes a good bra.”

Wakefield-Scurr set out to change that, establishing the Research Group in Breast Health with some basic equipment, a PhD student, and a lab technician. In 2009, she published the first-ever paper on the biomechanics of the breast in three dimensions, which made a discovery that ran counter to what many assumed about breast movement.

“In the earliest papers that were written and published, breast motion was measured only in the up-and-down direction, because that was the only motion considered,” says research associate Brogan Horler. “It wasn’t until our research that we confirmed the breast moves in three dimensions: up and down, forwards and backwards, and from side to side. We also found the movement of the breast almost mimics a figure-eight formation, not this rigid, parallel up and down.”

That information had huge implications for the sports bra industry, who had been designing for the wrong kind of motion control. Now, instead of trying to account for up-and-down movement, they also needed to consider side-to-side and in-and-out. As Wakefield-Scurr pressed on with her research, even more factors came into play. The research group found that different breast sizes and shapes move differently, and different types of exercise—even different intensities of the same exercise—cause the breasts to move in different ways. With every study, it became more clear that a blanket approach to sports bra design simply didn’t work. Breast support needed to be customized for a range of breast sizes and activities.

Manufacturers weren’t really sure how to do this. Sports bras had been constructed from the same general template for years, despite that template being pieced together from guesswork. To educate brands on the new science, the Research Group in Breast Health opened their testing protocols to designers and brands in 2013. They also created a one-day workshop for bra manufacturers titled “The Science Behind Breasts and Bras.” In this program, designers could develop their knowledge of breast anatomy, biomechanics, breast support, and bra fit.

Today, Portsmouth is the premier destination for independent sports bra testing, where prototypes and products are run through a series of tests to determine not only individual effectiveness of their sports bra, but how it compares to other brands. Over the years, the group has tested thousands of sports bras and prototypes from brands around the world, collecting unbiased data on the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of each product. In doing so, the Portsmouth researchers have created a massive database of products and prototypes, which allows them to tease out the variables for what makes an effective sports bra.

A call for more sports bra science

Not all sports bras go through such rigorous testing. In fact, the majority of sports bras on the market today lack any sort of independent biomechanical testing. Some brands, especially those marketing a wide range of clothing for a wide range of clients, treat sports bras as an accessory. Their products follow the same general pattern each year, with different fabric colors or design elements to match the trends of the season. Other brands see testing as overkill—surely, a sports bra can’t affect athletic performance the same way as seemingly more important gear, like shoes. No champion has ever credited a win to her undergarments.

But maybe they should. In recent years, Wakefield-Scurr and her team have expanded their horizons to examine how breast biomechanics impact the whole body. What they’ve found has proven the value of a good sports bra. One study found that unsupportive sports bras are linked to slower marathon times, and this slowdown is increased exponentially with cup size: a woman with a 36DD cup size would finish a marathon over 34 minutes behind a woman wearing a 36A, even if they had similar fitness levels and a similar training experience. Another found an unsupportive sports bra shortens a woman’s stride by an average of four centimeters—over the course of a marathon, that adds up to one mile of extra running.

Sports bras are also proving to be an essential injury-prevention tool. Excessively bouncing breasts take their toll on the body, causing the muscles and shoulders to tense. Over the course of a long workout or race, this can cause fatigue and a breakdown in proper form, upping the risk of injury. This top-down approach makes sense, given the location of the breasts, but a Portsmouth study found the body also compensates for excess movement from the bottom up. “When we had women run across our force plate in low-support sports bra, we found they were putting more force through their feet,” explains Horgan. “When there is lower support of the breasts, women are cushioning themselves to reduce the breast bounce that’s going on, so they’re not striding as confidently. In terms of injury, that impacts the ankles, knees, legs, and hips—all because of the breasts.”

Simply put, a good bra is essential for athletic performance. Yet subpar sports bras still exist, and some are even sold in large quantities. Searching for sports bras online unveils thousands of options, from thick garments resembling Kevlar vests to pastel-colored crop tops with a dizzying array of delicate straps intersecting across the back.

“The difficulty is that there’s not a standard to make something a sports bra,” Horgan says. “I could cut off the bottom of my shirt and say, ‘Here we are! Here’s a sports bra!’ There’s no rules to say you need to reduce this much breast movement during running to say that it’s suitable for running. It’s a shame, and we need to change that.”

“Nipples and breasts were flying everywhere”

“Nipples and breasts were flying everywhere” is not the typical way people describe the start of their career path, but then again, Dr. Dierdre McGhee is a bit of a trailblazer. While working as a sports physio in Australia in the mid-2000s, McGhee found herself wincing almost every time she worked with female athletes. “I’d be watching these basketball players, and their breasts would be bouncing up and down. I kept saying, ‘Look, we’ve got to get your breasts more supported.’”

Time and again, McGhee was stunned by how many female athletes were wearing an inadequate sports bra. Some defaulted to the team-issued bra, while others chose their bras based on the recommendation of a friend or teammate. They believed that one bra could work for everyone, but McGhee knew better. After practices, she would take field trips with her athletes for individualized recommendations: “I’d point to specific bras and say you can buy this one, this one, or this one. And they’d pick one they liked and come to me in the fitting room, where I’d say ‘Well, you’ve got the right brand, but now you’ve got the wrong size.”’

Every time she fitted an athlete with the correct garment, in the correct size, the response was always positive. Not only did athletes perform better because they were comfortable, they also felt more confident. Both translated to better sport performance. Wearing a better sports bra was a literal game changer.

How to find a sports bra that actually fits

Studies show that eight out of ten women don’t know their correct bra size, much less how to find the correct fit. Most simply guess, trying on various garments in the dressing room until one seems about right. They don’t have a Dr. McGhee in their lives, dispensing frank and accurate advice in the fitting room of a bra store.

“I was thinking we really needed to improve the way we educated women about this,” says McGhee. “I wanted brands to make better sports bras, and I wanted women to wear better sports bras. I’m a scientist, but a clinical one. I’m very patient-focused, and because of that, I work to figure out what my patient’s needs are. And they usually need a better bra.”

McGhee took her ideas to Julie Steele, a biomechanics professor at Australia’s University of Wollongong, who shared her passion for women’s health. Together, they formed a research group to understand the science of breast support: Breast Research Australia, or BRA.

BRA researchers study breast biomechanics in relation to sports bra design and bra fit, with a specific slant on how sports bras improve enjoyment of sport and overall quality of life. They’re interested in developing solutions for all women, from elite athletes to large-breasted women to women who have undergone treatment for breast cancer. Finding the right sports bra is not just about telling someone their cup size; it’s about taking into consideration all the factors of the wearer’s body and what she’s doing while wearing it.

The velocity of bouncing breasts

Take, for example, running. In one hour of running at a pace of 10 minutes per mile, a woman’s breasts will bounce 10,000 times. Faster runners will have an even higher bounce rate, and larger breasts will have more velocity than smaller ones. When it comes to sports bras, the majority of women fall on one of two ends of a belief spectrum: either they try to stop the bounce altogether, or they assume such a feat is impossible. The truth is somewhere in the middle.

“The problem is that these brands keep saying they stop the breasts from bouncing, and that just doesn’t make sense. Breasts are made of fat, and fat is a liquid. You can’t compress a liquid,” says McGhee. “When bras are trying to stop breast movement, or when they’re trying to say they’re the best bra because it limits breast bounce by 80%, that’s the wrong marketing strategy.”

BRA’s research confirms this—the most restrictive bras are often the most uncomfortable ones. A good sports bra doesn’t restrict, but makes sure the mass of the breast is supported as it moves up and down. This usually takes one of three forms: compressing the breast against the chest wall, lifting them from below (done with a seam or underwire), or completely encapsulating the surface of the breast in cups. Each style must walk the fine line between discomfort from the breast moving and discomfort from the breast being overly constricted, which can cause chafing and make it difficult to breathe.

“I’m not looking for breast movements to stop. I’m looking for them to move well,” says McGhee. Once athletes renounce the search for a motion-stopping bra (which doesn’t exist) and instead focus on support, finding a comfortable—and effective—sports bra becomes much easier.

The Pied Piper of Sports Bras

Since launching BRA in 2007, McGhee has become the Pied Piper of sports bras in Australia, carrying the message of proper fit to physical therapists, sports physicians, coaches, and athletes. She educates Olympians and elite athletes at the Australian Institute of Sport and other large sporting organizations, at hospitals treating breast cancer patients, in the BRA lab, and through a smartphone app. Every time she talks with athletes about sports bras, she listens to the issues they’re having and tries to find solutions. When working with a large group of female endurance athletes, for example, she noticed a common complaint was friction—not in the typical areas under the breasts, but on top. Further research exposed a large gap in the knowledge of bra design.

“Most sports bra design and research is just looking at the bra by itself. If you’re a straight designer or an engineer, you’re looking at that narrow field,” says McGhee. “But because we’re clinicians, we go broader, and we see, ‘Oh, well, she’s actually running with this little vest on, and she’s got two water bottles sitting here, and they’re going to move up and down on her breast. So we have to look at how that affects breast movement and what’s happening with her skin. You can’t just look at the bra, you’ve got to look at what the woman is wearing on top of the bra, you’ve got to look at the athlete’s experience, and take all of that into account in bra design.”

User experience is the central theme of research at BRA. In working with older women, McGhee and her team discovered that as the skin becomes drier, thinner, and less elastic with age, women report an increase in frictional injuries caused by sports bras. When studying women with large breasts, McGhee found they laugh at the sizing options offered by the sports bra industry. “They suffer the most, really,” says McGhee. “Even today, with all the research we have, hardly any sports bras are designed for women with large breasts. What [sports bra manufacturers] call large is not what we call large. We’ve measured women using 3D scanners, and discovered women who have 3.1 liters of breast tissue. We wouldn’t call you large unless your breasts were over 1,500 milliliters of volume.”

To put that amount in context, 1,500 milliliters is roughly three pounds of breast tissue, or a bra size of 36F. Many mainstream bra manufacturers stop at a D cup, despite the average bra size in America clocking in at 34DD (cup sizes go up to I). When they do offer expanded sizes, it’s not unusual to see their DD-cup bra is the same model as their B cup—hardly the support needed for the velocity and weight of the larger breast.

McGhee’s research shows this is a major barrier to exercise: the larger the breast size, the less likely women are to engage in physical activity. If women feel discomfort, pain, or embarrassment about excessive breast movement, they simply won’t exercise. As obesity rates climb around the world, it becomes ever more important to remove barriers to exercise. A supportive sports bra may change the game for elite athletes, but it may be even more important for the everyday woman wanting to run her first 5K or sprint triathlon.

3D printing to the sports bra rescue?

Perhaps sports bra shopping would be easier if the process were automated. A woman could enter a scanner—something similar to the devices we walk through at airport checkpoints—and get a 3D rendering of her body. A printer would spit out recommendations of bra styles and sizes for ease in shopping. Better yet, it would print out a bespoke bra that fits every curve of the wearer’s body perfectly.

The idea sounds like something out of a futuristic movie, yet the technology is already in place. 3D scanning has moved into the fashion industry in recent years, with retailers and smartphone apps using 3D scanners to help customers find their perfect fit. Armed with their measurements, shoppers can navigate online or brick-and-mortar stores with ease, feeling confident the clothes they pick will fit and flatter their particular body type.

The application of such technology is a bit trickier for sports bras, however. A T-shirt, which simply covers the torso, is supposed to be forgiving. By contrast, a sports bra must fit the contours of the wearer’s particular anatomy, or it won’t work. A woman who wears a size 36C bra is not going to have an identical breast shape or distribution as another woman with 36C breasts. Breasts can be round, asymmetrical, bell-shaped, conical, close-set, wide-set, or teardrop-shaped. Every 36C woman, despite having the same bra size, will fill out a sports bra in a different way.

If a bra is too tight, it can restrict breathing. Too loose, and it might cause friction injuries. If the breasts bulge out of the top (colloquially described as “quad boob”), motion won’t be effectively reduced. The bra also has to be easy to put on and take off, which can be a tall order for something that’s supposed to be skintight. Fabric panels should be placed in strategic areas aligned with the body’s sweat maps to transfer heat and moisture away from the body. It should be lined with a fabric that doesn’t irritate the sensitive skin of the breasts and nipples. And ideally, it would also be stylish—this is a fashion item, after all.

No wonder it’s so hard to find the perfect sports bra. It simply doesn’t exist. (Yet.)

Dr. Adriana Gorea is a researcher in fashion and apparel studies at the University of Delaware who studies new technologies for sports bra design. Prior to academia, Gorea learned the ropes of the sports bra industry at Adidas, where she worked in the development of seamless knitted sports bras with embedded textile sensors. She became knowledgeable in how to make a sports bra—but was frustrated that there was not much “why” behind the bra design process.

“I learned by being firsthand into design and development that there’s not much science,” says Gorea. “There’s so much technology—you have all these amazing knitting machines that will have 2 million stitches in a sports bra. But how each stitch is engineered is pretty much trial and error. It’s more about Oh, this is pretty! or Oh, this is gonna shrink. Or Oh, let’s make this in five sizes and in pink. There is not much science behind sizing.”

Most of the innovation in sports bra design to date hasn’t really been innovation, but the application of pre-existing solutions. “The reason why many sports bras are so thick and tight is because many companies make sports bras using existing templates, without researching. They just use fabrics that are already available,” says Gorea. “Then they look at consumer feedback on their previous model bra, where they learn the main complaint is that the straps keep coming off, for example. Okay, so let’s just cross them. They keep making a new product with the same materials, but keep adding features: we add on padding, we add on binding, we add on zippers, we add on snaps to make them adjustable. Then you end up with this bulky product, because we keep adding on features using current elements.”

Gorea’s research suggests a better way—set aside the current template and start over. This time, build the bra with science in mind, starting with the very basic material. Her research on sports bras focuses on the fibers used to make the fabrics that eventually become the garment. Instead of the thick customary nylon or polyester blend with spandex, Gorea has identified ways to engineer fabrics that maximize the potential of seamless knitting technology, building a thin—yet effective—multifiber engineered fabric that could create an adaptable sports bra.

Her approach is to engineer fabric changes in response to sweat. When the fabric is dry, it remains soft; when wet, it compresses and thickens to give support. This allows for the creation of a garment that is light but not flimsy, skintight but not irritating, compressive but not constricting. It can stretch to easily slide on and off the body, and immediately recover its shape. More importantly, it will eliminate the need to buy five different bras for five different sports—a responsive bra will be both soft and comfortable during yoga class and tighter and more supportive when running.

The responsive fibers and fabrics sound high-tech, but they’re actually the oldest trick in the book. Flowers wilt when they lack moisture and lift after you fill the vase. Pine cones open their scales when dry and seal up when wet. Your hair is flat in dry climates and frizzy in humidity. Natural fibers, like wool, respond to moisture, too. Using nanoscience to re-engineer natural fibers and using knitting technologies to amplify those properties at the fabric level creates a structure that is responsive, soft, and surprisingly strong.

The next major change in building a better sports bra is to rethink the way bras are built. Currently, many designers use patterns to cut out pieces of fabric to be stitched together. These stitches are problematic, as seams create friction points on the bra that constantly rub on the skin (any woman who has experienced “bra burn” can attest to the searing pain of such an affliction). There’s also the sustainability factor, as cutting bra elements from a sheet of fabric creates scraps, which become part of the 57 billion tons of textile waste the global fashion industry generates each year.

Knitwear technologies can eliminate all of those problems. Knitting technology is so advanced, scientists have created flexible yarn from human skin cells, which can be knitted into unique patterns for tissue grafts and organ repair. Gorea says such manufacturing technologies can take the responsive fibers and create skin-like fabrics sculpted into a seamless sports bra that fits the body of the person wearing it. 3D body-scanning technology could be used to confirm this fit, or perhaps even one day create a bespoke bra.

“We wouldn’t be so concerned with sizing, because you really should just be able to put a layer on, and the fibers will be activated by your own body,” says Gorea. “It will hug and support you when you start moving. It will deal with your own heat sweat maps and your own shape and anatomy and sensitivity.”

In other words: It might finally be the perfect sports bra.

The science is there. So is the technology. So why aren’t we in the midst of a sports bra revolution?

The short answer: Money.

It costs money to conduct research. It costs even more money to develop new textiles or formulate new solutions. It’s also costly for brands to offer an expanded range of sizes, cater to a niche market, or launch an entirely new product. The sports bra is a commercial product, and the manufacturer’s ultimate goal is to turn a profit. The easiest way to do that is to offer a familiar product to a customer base who has long established they’ll buy it.

“It’s scary for a company to completely change what they’ve done,” says Gorea. “It requires a huge leap of faith.”

There also might be a lack of awareness that a better design even exists. Science has long had a public relations problem, publishing their discoveries in journals using academic language that is often out of touch with the general public. This can make it hard to bridge the gap between research and application, says Horlan. “Universities and research in general can sometimes be quite guilty of producing and finding out lots of information, but not getting it out there into the world. [Until we opened our testing center], we were finding out lots and lots and lots about breast biomechanics, but companies weren’t using that information.”

Money also comes into play, as consumers are more likely to buy a $20 sports bra than one that costs $300. Innovation costs money, but innovation is also an unknown—many female runners know the frustration of dropping a large sum on a much-hyped brand or style, only to discover it isn’t much different from the other bras in their drawer. That may be because they bought the wrong size, it may be a poor design, or it may simply be that the bra just isn’t right for her body type or sport. Regardless, trying new sports bras can be an expensive pursuit.

Almost every endurance sports forum on the internet has a sports bra thread, where women share product recommendations. Some also offer hacks for making their bras more effective.

On one such thread within a Facebook group for female runners, a runner writes of buying low-cost bras from a discount department store and “double bagging,” or wearing two at a time. Another fortifies her bras with kinesiology tape on the breasts before long runs. Someone else chimes in to say she also uses tape, but to cover the clasp on the back of her bra to prevent chafing. It’s not unusual to see a specific bra recommendation prefaced with “It’s not perfect, but…” They’re not perfect, but we still buy them.

“I think people need to come together and say, ‘Actually this is really uncomfortable, and I’m not going to wear it.’” says McGhee. “I would love to spend time with the designers and go, look, this is what we need to do. These are the issues women are having, and this is what needs to change. I think designing a bra is an art. I have admiration for those designers—there are some really lovely designers out there, really smart ones. But I think they need to have that science behind it, too.”