The Making Of A World Champion

Mirinda Carfrae’s 2010 win in Kona was no fluke. It was a result that was carefully and methodically crafted by her fierce yet under-the-radar coach.

Written by: Kim McDonald

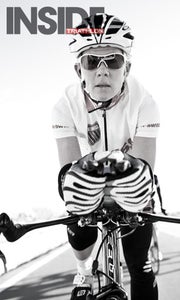

Photographs by: John Segesta

This article originally appeared in the May/June issue of Inside Triathlon.

As news about Chrissie Wellington’s last-minute withdrawal from the 2010 Ironman World Championship rippled through the nearly 1,800 athletes preparing to slip into the still waters of Kailua Bay in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii, most assumed that Mirinda “Rinny” Carfrae was elated, breathing in a sigh of relief. The 2009 runner-up, Carfrae wouldn’t have to compete against the pre-race favorite and three-time Ironman world champion.

But Carfrae wasn’t relieved. Outside the King Kamehameha Hotel, where Carfrae was resting, she was in a state of panic.

“When Chrissie pulled out,” said Siri Lindley, Carfrae’s long-time coach and confidante, “My phone started ringing and Shannon, Rinny’s manager, was on the line saying, ‘Get your ass out here. Rinny needs you right now.’ So I’m sprinting through the hotel and when I get there, Rinny is saying, ‘What in the world do we do now?’ I said, ‘Nothing changes, absolutely nothing changes. Race your race.’ And she said, ‘Who am I going to swim with?’ And I said, ‘Nothing changes. We stick to The Plan.’”

The Plan for last year’s Ironman World Championship, a race that Carfrae had dreamed of winning for most of her life, was a carefully scripted guide that Lindley had put together. It spelled out who Carfrae was expected to swim behind, the way she expected her to ride and how much faster she expected Carfrae to run along the Queen K Highway than she did in 2009 when she broke Wellington’s 2008 Kona marathon record of 2:57:44, setting her first marathon record for the race of 2:56:51, in what was her first-ever marathon.

But The Plan in a larger sense was also the map to success that Carfrae, who was a 70.3 superstar and had never done an Ironman prior to Kona in 2009, and Lindley, a 2001 ITU short-course world champion who had never put together an Ironman training plan before Carfrae’s 2009 debut, developed collaboratively. They perfected it through trial and error and had closely followed it over the previous five years. It was a plan that culminated in Carfrae winning the 2010 Ironman World Championship with a world record-breaking run split of 2:53:32.

How did two athletes with so little Ironman experience create a recipe for such success in Kona in such a short amount of time? Many of the clues can be found in Lindley’s evolution from a struggling age-group triathlete to a world champion, the instincts she’s honed as an athlete and coach, and the way she’s learned to cajole top-level performances from her athletes.

Since 2003 Lindley, who dominated the ITU World Cup rankings in 2001 and 2002, has developed into one of the world’s premier triathlon coaches. She coached Susan Williams to a bronze medal in the 2004 Athens Olympics, Carfrae to her 2007 Ironman World Championship 70.3 title and Samantha Warriner to an ITU World Cup series overall championship (before the ITU’s World Championship Series existed). Besides Carfrae, Lindley’s current athletes include long-course champions Leanda Cave and Kate Major (Cave is also a former ITU short-course world champion), and up-and-coming ITU short-course pros Chris Foster and Hayley Peirsol.

Despite her success, Lindley remains off the radar as a coach. When most people think of Siri Lindley, they think of Siri the athlete, not Siri the coach.

This is not surprising. Unlike most high-end coaches who pay their bills and gain exposure through webinars, DVDs, online training programs and mass-marketed coaching clinics, Lindley keeps a low profile, focusing time and energy on her 15 elite pros and 10 age-groupers, many of whom train together under her watchful eye in Los Angeles and at her desert training camp east of San Diego in Borrego Springs. One of the main reasons she moved from Boulder, Colo., three years ago, in fact, was her concern that the area had become overrun with triathletes.

“There was too much going on there, too many distractions,” she said. “I wanted to focus on what we need to get done.”

Her move to Los Angeles in 2008, though, came at a price.

“I had 10 athletes and I lost nine out of the 10,” she said. “Rinny stayed and I built the current team around Rinny. It gave me a blank slate to create an environment for Rinny to succeed.”

While Los Angeles and Borrego Springs now provide Lindley with what she calls a “more powerful environment” as a coach, one that allows her to better control and monitor her athletes’ training, her propensity to stay out of the limelight and train her athletes away from the masses (much like her former coach Brett Sutton did) have fomented rumors about her training methods.

Foster heard the warnings before he joined Lindley’s group last September: Siri will overtrain you. She’s a control freak. You’ll have no voice. If you have any ideas, forget it—you won’t be able to express them. She doesn’t work on technique. She gives everyone the same workouts. You’ll be injured or retired in a year.

“They had this perception that because her old coach was Brett Sutton, she just hammers and hammers you, without rhyme or reason,” said Foster. “They said she has this formula, and she sticks to it, and good luck. But that was nowhere near the case. I realized these people were ill-informed.”

When super swimmer Peirsol, the younger sibling of backstroker and five-time Olympic gold medalist Aaron Peirsol, decided two years ago to embark on a career as a pro triathlete, several coaches courting her warned her parents that if she went with Lindley she’d end up injured and overtrained. But their efforts backfired when Peirsol’s parents, skeptical about the coaches’ motives and curious as to why Lindley had never contacted them about coaching their daughter, asked Lindley if they could meet with her and observe her training sessions in Borrego Springs. They ultimately chose Lindley.

“Hearing that stuff used to just destroy me,” said Lindley of the negative rumors, “because I care so much about what we do, about taking care of my athletes, making sure that we’re happy and that they understand we’re on the same page. I want them to feel that we are in this together.”

Known as a protégé of Sutton, who is most famous for molding Wellington into a champion while she trained with him in the Philippines and whose sometimes brutal workouts are legendary within the triathlon community, Lindley understands why people are misinformed. But Lindley makes no attempt to distance herself from her former coach, saying she has nothing but the highest regard for him.

“Brett was the greatest coach,” Lindley said. “He was my mentor. He believed in me when I didn’t believe in myself. He’s just an incredibly smart, intuitive man. You look and see what he’s done with these athletes and it’s incredible. So a lot of his principles I, of course, have followed.”

Spend time with Lindley, however, and you’ll immediately discover that she is very different from Sutton. Lean, tanned and fit despite the nine years that have passed since her last professional race, she has an infectious smile, upbeat personality and irrepressible energy. While some of Sutton’s former athletes describe their old coach as blunt, unapproachable and often critical, Lindley is the type of person who goes out of her way to make people feel at ease. She forms close bonds with her athletes, feels empathy for them through their ups and downs, and constantly reminds them that “we’re in this together.”

“Brett could be a real hard-ass and he used different psychology—not the positive reinforcement, but the negative reinforcement,” said Cave, who was once coached by Sutton. “I was always under the belief that I was not good enough under Brett. Siri’s always positive. She’s never said a bad word to me or anybody I know. She’s someone I consider a friend.”

Major, an Ironman champion who joined Lindley’s group last year, agrees: “Siri always encourages people to just have fun. You are working, but to go fast you have to enjoy it.”

But beneath Lindley’s easygoing exterior is another, very different side to her personality—an inner core of mental toughness and cunning that Sutton came to respect. Those who know her well point to this toughness as the reason she became the world’s No. 1-ranked triathlete.

“‘Fierce’ is the best word to use when describing Siri,” said Loretta Harrop, Lindley’s former training partner and longtime friend who won silver for Australia in the 2004 Athens Olympics. “She is fiercely competitive, fiercely passionate, fiercely determined and fiercely protective of anything that means a lot in her life. We were the biggest rivals, yet the best of friends. Both of us had a huge respect for each other’s unwavering desire to win.”

Sutton echoes Harrop’s sentiment: “People underestimate her natural intelligence. The bubbly personality she exudes sometimes hides the very shrewd thinker that she is. When you have to cope with certain problems in one’s own career to become successful, it makes for a better coach.”

Lindley was hardly a natural when it came to triathlon. She was a college athlete who played field hockey, ice hockey and lacrosse at Brown University. She even competed for a spot on the U.S. national lacrosse team. But she didn’t bike and could barely swim. Her first triathlon, a local sprint race in Colorado she entered at age 23, was in her words “a complete disaster.” But she was hooked. And by sheer will and determination she clawed her way to the top, first as an amateur and then as a professional.

“For me, triathlon was the vehicle through which I found myself,” Lindley said. “I went from being a very insecure, scared kid to coming to where I am as a human being. The journey for me was much more powerful than the results I got or the sponsors I had or any money that I made.”

It also convinced her that anything is possible if you have enough motivation to pursue your dream, a lesson she is fond of reminding her athletes.

“I’m living proof, because I’m someone who people would never have guessed would eventually become a world champion,” she said. “So I’m a believer that anything is possible. You just have to figure out the right recipe.”

If bouncing back after failures and overcoming shortcomings as an athlete is the path to success for a future coach, Lindley has had more than her fair share. In 1999, she completed the ITU World Cup season ranked fourth in the world, the second American behind Barb Lindquist. Setting her sights on qualifying for the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, she moved to Cronulla, Australia, near Sydney and spent six months training under New Zealand coach Jack Ralston. But in her first Olympic trials qualifier, the lead pack swam away from her, a mistake that contributed to her not being selected for the U.S. team. Devastated after what she called the biggest failure of her life, she went to Sutton, who was coaching Harrop, and absorbed the lessons that soon transformed her from a perennial fourth-place finisher into a world champion.

“I learned so much from Brett,” Lindley said. “He is a really brilliant master of minds. He has a great way of knowing how to get into an athlete’s head, sweep out the stuff that’s getting in the way and shed light on the things you need to be working with as aspects of your personality that are going to allow you to be the best that you can be.”

Sutton figured out what was missing, Lindley says, and in the process provided some of the most important lessons she’s learned in life.

“I was one of those athletes who would say I’m going as hard as I can; there’s no way I could possibly go harder,” Lindley said. “But because I had never gone any harder, I thought that was my limit. I set limits for myself when I said this is as hard as I can go. His hammering me so hard that first month was brilliant because if I could make it through that, it would give me this newfound belief in myself. By torturing me he was giving me this incredible gift. Not only did I survive, but I had my first podium in a World Cup three months later.”

Beyond Lindley’s high tolerance for pain and her determination to win, Sutton observed something else about the American: “She was always very good at summing up other people’s problems on the squad,” Sutton said. “Without her knowing it, I could ask a question of one of her training partners and she would give an insightful answer. She had an inquiring mind. She was always pimping me for answers.”

When Lindley won the ITU World Championships in 2001, she considered retiring but decided to give it another year to prove her No. 1 ranking wasn’t a one-time fluke. It wasn’t. She won four World Cups in 2002 and the overall ITU World Cup title.

Nevertheless, she felt there was something bigger out there for her, something that would combine what she learned as a psychology major at Brown with her experiences as an athlete—something that would allow her to guide others through a journey similar to the one that had transformed her life.

“Literally the day after I retired I knew what I wanted to do,” Lindley said. “I’d always watched my training partners and loved the differences in personalities, looking at what worked for someone and not someone else. That really intrigued me. We were always training in these out-in-the-middle-of-nowhere places and that was my entertainment, figuring it all out.”

It’s a Thursday morning in Santa Monica, Calif., and Lindley pulls up to the beachfront park in her white VW station wagon stocked with water, gels and extra tubes. Her upbeat comments and lighthearted jabs spark laughter among her athletes joining in for the day. There’s Peirsol, whom Lindley affectionately refers to as “Hay-hay”; former fashion model turned pro triathlete Jenny Fletcher, whom Siri calls “Fletchy”; Major, whom Lindley often greets by shouting “May-jor!” in Spanish; Japanese ITU athlete Misato “Taka” Takagi; and Foster. Lindley’s tone grows more serious when she tells her athletes what she expects from them on today’s ride up Topanga Canyon Road. As we begin the ride north through the morning traffic, she drives close behind, monitoring everyone’s cadence and form.

Like Sutton, Lindley is convinced her athletes can make the greatest gains while training as a group and insists on being with them at the pool, the track and on many of their group rides to correct mistakes.

“It’s unbelievable how much more you can get out of an athlete by having them there in person,” Lindley said. “If something’s not working, I’ll be able to see right away because I’m right here. What’s happening when they’re falling apart? Is their cadence falling off? Are their shoulders getting too tight? My being there to observe and react and make a change immediately is something I rely on to make those major gains.”

Like Sutton, who applied his experience as a thoroughbred horse trainer to read the body language of his athletes, Lindley also has an uncanny ability to read people: their moods, their fears, the things they unconsciously do when they reach their physical limits.

“She’s very good at reading athletes,” said Cave. “She caught on to what I need, which is to wind down and relax. I don’t like talking too much before races, so she always sends me these awesome e-mails with big bold letters and exclamation marks. It’s almost like I can hear her when I’m reading the e-mail.”

Lindley acknowledges she’s not a numbers person, but there’s a reason: “There’s a time and a place for heart-rate monitors and power meters, but if you’re depending on them every single day, they put a ceiling on you,” she said. “Because if you hit these numbers, then you think, ‘Oh great, I’m where I need to be.’ But what if you could be this much higher? What if you could go by perceived effort and get 15 percent more out of yourself?”

In the increasingly competitive world of ITU and long-course racing, now being won by tenths of a second, Lindley is convinced that mental toughness and confidence in one’s ability to push past pain are what separate winners from losers. It’s the mental side that allows people to break barriers, win races and achieve their true potential. So she constantly challenges her athletes with workouts that take them to the limits of their ability.

“My philosophy as far as racing is, your biggest competitor is yourself,” she said. “I never say things that are impossible. But I will always tell them basically something that seems impossible to them, but I know it’s not. So then, it’s a matter of who’s got the guts to believe in themselves, to believe in what I’m saying.”

Justin Trolle, a New Zealand ITU coach living in Colorado Springs, Colo., says this style of coaching, common in Australia and New Zealand, is one of the reasons Aussie and Kiwi athletes are so mentally tough, so hard to beat in close races.

“If it’s raining outside, an Australian or New Zealand coach is going to send you out on the bike,” he said. “In the U.S., they’re going to put you on a trainer. We have a tendency to soften our athletes too much, so when push comes to shove, they don’t have that aggression.”

Later, he added: “I see where Siri is coming from. If you push an athlete to the limit, then back off, it resets the limit. When the pressure’s on and things are hurting, they know what to expect, so it doesn’t shock them. Winning is going to hurt. Winning never feels good until after you cross that line. And I think Siri is particularly good at breeding that toughness into them.”

Lindley makes no bones about expecting her athletes to go to their limits and warns them that she has little tolerance for unmotivated, uncommitted people.

“I remove people who aren’t 100 percent,” she said. “When you have one person in the group who isn’t giving 100 percent, even though they may be slightly motivated, it affects the rest of the group.”

She also has no tolerance for those who don’t follow the training programs she develops collaboratively with each of them. One of the most recent casualties of Siri’s program was Desiree Ficker, the runner-up at Kona in 2006 whom Lindley was training for last year’s Ironman Wisconsin. Lindley says she gave Ficker four days off before the race, then found out from the postings of Ficker’s friends on her Facebook page that she had done a track workout and time trial before the race. After dropping out of Wisconsin, she ran the NYC marathon and again, says Lindley, never told her coach.

“It’s like entering a relationship. You come to me and I’m going to devote myself to you. That’s what my major weakness is,” she said, pausing while trying to find the right words as tears welled up in her eyes. “Something like Desiree disappearing really breaks my heart because I’m choosing to believe in them 1,000 percent, too.”

The lessons that Lindley learned the hard way after failing to make the 2000 Olympic team are now the mantras she repeats to her athletes: Believe in yourself. Leave no stone unturned. Experience everything in training you expect to experience in a race. And they are the principles with which both athlete and coach used to design The Plan that guided Carfrae through her first Ironman and then her first Ironman World Championship win.

Many coaches might have tried to prepare Carfrae for Kona with one Ironman after another. But Lindley wanted her to retain her short-course speed and build her strength by training her to race faster 70.3s. With no background in 70.3 racing, much less in Ironman, Lindley didn’t know if that approach would work. But her instincts told her it was the way to go.

“I told Rinny, ‘I don’t know much about this, but this sport is going to transform just like every other distance has in triathlon, and I’m going to train you to race it just like an Olympic-distance race back-to-back,’” Lindley said. “And that’s how we approached it: trial and error. I adjusted her training to what we needed to do to hold that same Olympic distance effort for a half-Ironman.”

In October 2007, the two brought the rest of Lindley’s athletes to the Big Island for a training camp geared toward preparing for the Ironman World Championship 70.3. But the more important subtext was learning about Kona. They watched the Ironman. They spoke to Mark Allen, Karen Smyers, Paula Newby-Fraser, Greg Welch, Wendy Ingraham and Scott Tinley.

“I asked millions of questions. I was very annoying,” Lindley recalled. “It was amazing how different everyone’s ideas were. I read old books on the Ironman. Rinny communicated her ideas and we communicated a lot about what our game plan was going to be.”

In the first few years of training together, Lindley took the driver’s seat, but she would always take into consideration what Carfrae thought about the program and make adjustments accordingly.

“Once I stepped up to Ironman, which was uncharted territory for the both of us, I think we evolved into a great team with a huge amount of mutual respect,” Carfrae said. “We were both 100 percent committed to racing Ironman at the highest level possible, and we both had our own ideas to bring to the table. We didn’t always agree, but we were able to put the puzzle together and work out what the absolute best plan would be.”

Carfrae won the Ironman World Championship 70.3 in Clearwater, Fla., the following month, which provided her with an entry into Kona for 2008, but the two decided to defer it until 2009, when Carfrae would be fully ready. At the start of 2009, Lindley says, “The game plan was geared toward having a totally awesome 70.3 season. Our long rides were getting longer, and our long runs were getting a little bit longer. We were doing more second runs. Things were changing, but not in any massive way. Then when we got to a certain point in our season, July 1, Ironman training started.”

While Carfrae was running faster off the bike, Lindley felt she needed to increase her efficiency and strength on the bike.

“Her pedal stroke was not strong all the way around, so we worked on that,” said Lindley. “She hated it and swore at me every day but eventually developed a nice pedal stroke. We were building strength with lots of hill climbing. I was asking her to do things a different way that really took her out of her comfort zone.

“What I knew is that this was a strength race. You’ve got to be strong from start to finish. So the most important word that came to my mind in every area was strength in swim, bike, run. It was all about building up her strength to go out on a six-hour ride or a two-and-a-half-hour run.”

While neither had done an Ironman, both coach and athlete had enough confidence in one another, enough of a stake in The Plan they had devised together, that there was no second-guessing, no need to see if it would pass muster with another coach.

“I’m sure I could have gone to Brett and said, ‘Please help me with this, help me understand what I need to do,’” Lindley said about her personal role. “But I needed to figure it out … I need[ed] to figure out if I had what it took to be successful as a coach, first at the Olympic distance, then 70.3, then the Ironman.

“This sport is still evolving and it is continuing to evolve in huge ways every year. I don’t want to be following the plan of the day—this is how athletes do Ironman. I wanted to use the things I felt comfortable with—the things that when I present them to the athletes who I know, if we execute them properly, this is going to be the result. I need to be in a place that’s comfortable, with a good gut feeling that this type of training is going to work. It has to be authentic to me. It has to be something that feels right for me.”

Carfrae’s 2009 race, in which she broke Wellington’s marathon record, was a conservative one, but that’s exactly what the two of them had intended. Their goal was long-term, to come back in 2010 with a faster, stronger race.

“I felt like I had the potential to race a fast Ironman, but you just never really know until you get out there and experience it firsthand,” said Carfrae about her 2009 race. “Even though I felt I ran well that day, I knew that I had the ability to run a faster marathon the next time around.”

Their formula worked in 2009 and again in 2010 and has given both the confidence that Carfrae’s on the right track to go faster still this year.

“There is a really wonderful and beautiful progression going from Olympic to 70.3 to Ironman,” said Lindley. “It really does all fit together. And you can take all the things that work for one distance and transform them and tweak them and make them work for the next.”

Carfrae’s win in Kona last fall was more than a victory for Lindley. It was vindication of Lindley’s decision to retire at the peak of her athletic career and confirmation that the same instincts that guided her to win the world’s most competitive short-course distance race—the ITU World Championships—could be applied successfully to help another athlete win the world’s most competitive long-course race.

“I think the biggest accomplishment that Siri felt from that win was coaching an Ironman athlete, not an Olympic-distance athlete, which was where everyone thought Siri’s expertise was,” said Harrop, whom Lindley visited in Australia to celebrate after Kona last year. “For Siri, the win has cemented in her own mind that she is not just a good coach, she is a great coach.”

Lindley’s mentor, Sutton, has even stronger words of praise, saying that with time and experience, “She will be the best triathlon coach in America.”

This article originally appeared in the 2011 May/June issue of Inside Triathlon. Click here to subscribe.