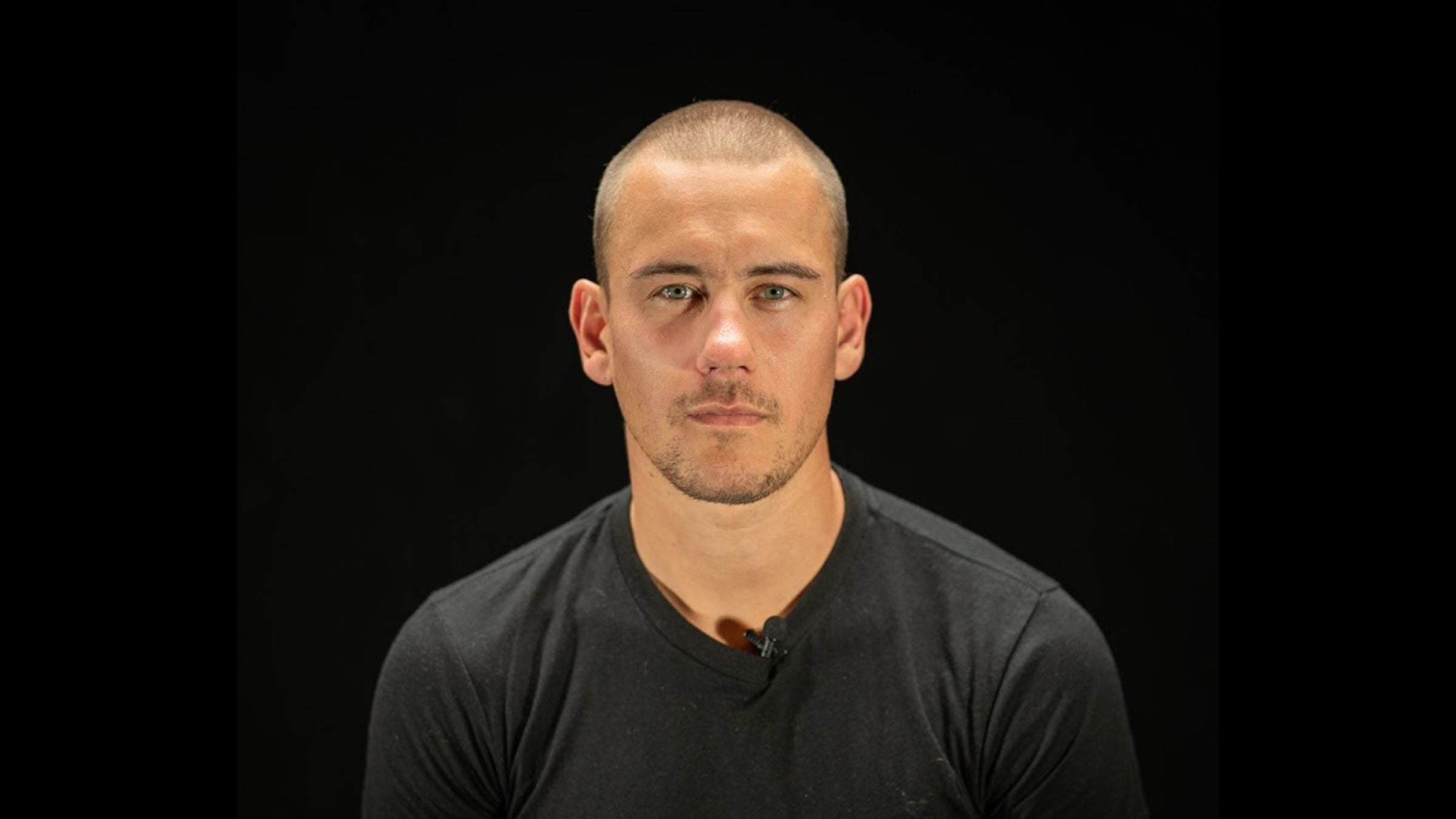

Exclusive Interview: Mikal Iden, Coach of Suspended Pro Triathlete Collin Chartier

Mikal Iden, older brother of Ironman world champion Gustav Iden, and a coach with the Norwegian Triathlon Federation, spoke out in the aftermath of Collin Chartier’s positive test for erythropoietin (EPO) in a doping scandal that has rocked the sport.

In his interview with Triathlete, Iden reiterated that he had “never” doped any of the athletes in his charge, nor had any prior knowledge of Chartier’s three-year sanction before April 24, when he received a brief, apologetic text from the triathlete and a link to the breaking news.

Iden also said he had little knowledge of EPO or L-Carnitine (a legal but controversial supplement to improve fat burning that Chartier also admitted taking) and hadn’t been contacted by the International Testing Agency (the not-for-profit organization appointed by Ironman to investigate anti-doping) despite Chartier claiming the ITA had concluded a “thorough investigation” into the case.

Initially a promising triathlete himself, Iden stopped pursuing a professional racing career in 2013 and began coaching in 2015. His personal highlights include representing Norway in the 2012 junior ITU World Championship in New Zealand, an event where teammate and future Olympic champion Kristian Blummenfelt finished fourth.

The Relationship

Iden began coaching Chartier in January 2022, and the two first met at the PTO’s Collins Cup in Slovakia the previous August—an event where Chartier was beaten by Gustav Iden in his individual match-up.

“In December, [Chartier] contacted me because he was looking for a coach for long distance, and he’d seen that the people I was coaching were doing well,” Iden explained.

Despite agreeing to take on the triathlete, Iden insisted that coaching long-course pros such as Chartier, Lionel Sanders, and Rudy Von Berg was secondary to his role with the Norwegian Federation where he helps train a squad of triathletes aiming for Olympic success under sports director Arild Tveiten.

“I give them a plan but tell them I can’t chase after them to ask questions about how it’s going,” he added, referring to non-Norwegian triathletes outside of the federation program. “This is not my main job, it’s my side job, something I enjoy doing of course, and something I put my time and effort into, but for it to work they need to give me information.”

Iden added that it wasn’t unusual to have no contact with the triathletes for long periods of time: “We could go weeks when we don’t communicate because they are taking in the training and everything is good. For me training is very simple: You do the plan, you sleep, you eat and things should work out fine. And if it doesn’t work out fine: Are you sleeping enough? Are you eating enough? And are there any other stressors in life? This is my way of working with these athletes.”

Iden said the second time he met Chartier was last summer in Arizona when he found an open window in his coaching calendar with the national federation to travel. At the time, Chartier was staying with Sanders at his home in Tucson ahead of racing Ironman Mont-Tremblant and the PTO U.S. Open in Dallas, with the season’s main focus on the Ironman World Championship in Hawaii in October.

“I’ve never coached athletes for Kona before, and I had the time available to go over there and invest in getting to know Lionel and Collin much better.

“Having someone tell them what to do is not the same as seeing them. I remember he [Collin] always started his swim intervals super fast and faded. I mostly observed what they were doing, just giving small tips on what to change.”

Chartier has since stated on the How They Train podcast that this was his happiest period in recent times, giving him the right mentality and training environment to win in both Mont-Tremblant in August and a surprise victory at the PTO U.S. Open in September. (For his part, Iden says he never took a percentage of Chartier’s prize money, including the $100k he won at the U.S. Open.)

Iden continued: “Collin was super happy because he didn’t need to think about food or recovery. There was no social life, it was us boys going to training and Erin [Sanders, Lionel’s wife] making food and life was good.

“He said it was so much easier than when he was training alone. He was optimizing his training, I’m there looking after him, and he’s training with Lionel. That’s how I saw it in that period.”

When Iden received the text from Chartier saying he had tested positive, Iden said he didn’t read past the subject line and instead searched online to find the ITA news release, the not-for-profit body contracted by Ironman to manage the results of the out-of-competition test in February.

Having called his parents and Tveiten, Iden decided to put out the following statement on Instagram:

I never thought I would have to make a statement like this…

I’m in shock and crying just now learning that an athlete I’ve been coaching for the last year has been doping.

I can’t distance myself enough from this action. It’s such a complete crash in my values it’s unthinkable.

The only positive I see from this is the anti-doping organization catching the athlete.

Thrust [sic] is going to be hard going forward.

The Doping Investigation

While Chartier claimed that after undertaking a “thorough investigation into whether or not this was a bigger doping ring in the sport” the ITA concluded he had acted alone, neither Iden, Von Berg, nor Sanders said the ITA had been in touch—a situation Iden himself described as “weird.”

He added: “I’m wondering the same. Why haven’t they contacted me? We were training for two months straight. I’m thinking that Collin has said we are in the clear, but still it’s weird that we are not contacted, because can you trust what he is saying?”

In response, the ITA issued the following statement to Triathlete: “The ITA’s I&I [intelligence and investigations] experts are conducting these investigations diligently, whilst ensuring that confidentiality and the integrity of the investigation is respected.

“For this reason, we cannot give you specific details regarding our investigative work on any case but can confirm that the ITA is acting upon any information accordingly and immediately.

“We cannot stress enough the importance of sharing any suspicions or knowledge of doping offenses through our confidential reporting platform REVEAL.

“We stand firmly with the triathlon community in the fight against doping – if you know something, it is your responsibility to speak out and help us keep your sport clean.” Triathlete reached out to Chartier for comment, but received no response as of this writing.

The Training Data

As Chartier’s coach, Iden also has access to his training data through the platform, Training Peaks. While Triathlete wasn’t able to analyze the data at this time due to client privacy, Iden said he saw nothing untoward in the numbers.

“We go off [blood] lactate [testing] and the threshold could change between 40 watts if you are having a good day or a bad day,” Iden explained. “I’ve seen a lot of comments that say you’d see if someone is doping. But if you’re training a lot and have fatigue, what you perform that day can [vary] so much. I see that with every athlete I coach.

“People say how could you not see [Chartier’s use of EPO]?” Iden continued. “Because I’m not looking for doping. I trust my athletes and in my head doping is not an option.”

Iden cited that the high number of variables, such as whether Chartier was training at altitude, what kind of bike he was riding, and whether he was dealing with injury issues, made it too difficult to challenge the athlete’s claims that he only started only doping in November—after his victories in Dallas and Mont-Tremblant and a disappointing 35th place finish in Hawaii.

“I don’t feel it’s that simple,” Iden added. “There were sessions that were really good, but the lactate was really high, so I would just think he was going way too high intensity.

“We could say because he was doing threshold intervals for such a high intensity for such a long time that maybe that could be an indication there was something wrong, but a lot of factors play in including heat, liquid, nutrition… it’s not easy to say it’s obvious. I [also] have no experience in it [EPO], so for me to say anything would be speculation.”

Chartier tested positive on February 10 when based in Girona, having completed earlier winter training camps in Mammoth Lakes, California and Cuenca, Ecuador.

Iden and the Norwegian squad were training in Lloret del Mar on Spain’s east coast, around 25 miles south of Girona and the coach recalls Chartier joining them for a couple of days along with a trip to Girona where the U.S. athlete gave them a tour and completed a bike test.

“I did a bike test on him the day after [they arrived] in Girona and the data was good, but not super impressive,” Iden said. “He’s a lightweight guy and a lot of other athletes can produce those power numbers. I could say he was in very good shape for February, but there could be reasons for it. He had one more year of training with me and, as a coach, I could believe that helps. But now I’m not sure if my training is the reason for anything. So, I could think I’m a good coach but it’s the other stuff doing it.”

Chartier’s Background

Chartier has claimed that he procured and learned how to administer EPO through the internet, saying he took it about three to four times each week from November and that no one else was involved.

However, Chartier’s LinkedIn profile also revealed that from March 2015 to May 2017 he was an undergraduate at Marymount University in Virginia, where he was the lead researcher working under Dr. Michael Nordvall in the study of Hemoglobin, Hematocrit and Anthropometric Alterations during the Competitive Triathlon and Cross Country Seasons.

Hematocrit is a measure of the ratio of red blood cells relative to the entire volume of blood. The more red blood cells, the greater the body’s capacity to transport oxygen around the body, which in turn should lead to an improvement in endurance. Chartier’s studies effectively monitored college athletes for changes in these biomarkers, leading to a 2017 thesis on the topic.

Dr. Nordvall told Triathlete that he built up a good rapport with Chartier, who graduated with distinction, but hadn’t seen him for several years. He was certain that the course material in no way would have educated Chartier on the application of EPO.

“No, absolutely not,” Dr Nordvall said: ”I can’t speak to what he did in his personal times, but there wouldn’t have been anything that led me to believe that any of his work indicated he would be going down a road like that. There was nothing about how to go about doping, which obviously is not something any institution would normally teach as part of an exercise science programme.”

Chartier hasn’t mentioned his studies publicly since the positive test, and Iden couldn’t fully recall whether they’d discussed it previously either.

“I think we once had a halfway conversation about him studying,” Iden said. “This is the problem. It’s almost embarrassing. I don’t know enough about this kind of stuff to even question him well enough.

“If I remember correctly, he was talking about mitochondria and long rides being important, but it’s not very scientific or out of common knowledge. People might blame me that I didn’t know this, but then is it a normal question to ask? It’s hard to remember every conversation.”

Iden also says he wasn’t aware of Chartier’s use of L-carnitine, a controversial drug that can help fat metabolism. While it isn’t banned in elite sport, it cannot legally be taken intravenously in doses of more than 100ml over a 12-hour period. In 2019, the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) banned Nike Oregon Project track coach Alberto Salazar for four years, with part of the charge relating to infusing prohibited amounts of L-carnitine.

“No, and again it’s not something I knew about,” Iden went on to say about L-carnitine. “We Googled it in the car the other day and I was like: ‘Oh, I’d never heard about it.’ So it could be that he said something about it, but I didn’t pick it up. There is also a language barrier between our conversations.”

When suggested that people would be surprised a leading coach hadn’t heard of L-carnitine, the 28-year-old replied: “It could be I heard about it, but I can’t say it’s something I’ve looked into. I’m thinking now that I’m embarrassed by my own coaching abilities and all this kind of stuff because I don’t know enough about it.

“Should I get a paper from anti-doping Norway on stuff that is borderline legal? I know things are illegal, because if we are going to a pharmacy when on national team camp, we go through the labels and ask our team doctor and if he says, ‘I don’t know’ we don’t take it. So, I’ve never much looked into this kind of stuff. It’s a world that I’m not interested in.”

Asked whether it was possible that Chartier could have the capacity to dope himself without assistance, Iden said: “It wouldn’t surprise me. He’s a guy who will fix stuff and do stuff and that’s also what I liked about him as an athlete. He would go on training camp when a lot of athletes are not interested. He’s a guy you wouldn’t need to ask him twice. I never got the feeling that he was working with someone else.”

The Norwegian Connection

Iden said he is confident he retains the backing of the Norwegian Federation. The current Norwegian squad he trains – including Vetle Thorn, who is ranked 51st in the world, and up and coming Solveig Løvseth, who placed third in a recent Word Cup race in New Zealand – train independently from Olympic champion Kristian Blummenfelt and Ironman champion Gustav Iden, who are coached by Olav Alexander Bu.

While it is not unprecedented for athletes to form their own training groups outside of the official federation structure, coach Iden refused to comment on why this was the case, nor why the Norwegian Federation protested against Gustav’s running shoes in the World Triathlon Championship Series race in Abu Dhabi in March. The protest was later dismissed with the On branded shoes found to be compliant.

Commenting on Norwegian sport’s anti-doping policies, Tveiten said in a statement: “Norway has a world-leading control programme. Anti-Doping Norway works systematically with, and spends significant resources on investigations. They have built up athlete profiles, including our athletes. They have blood profiles in addition to urine samples. ADNO conducts a significant proportion of its non-competition tests unannounced and targeted.”

The statement goes on to say that 78 Norwegian triathletes were tested a total of 353 times from 2018 to 2022, with 88 tests being carried out in 2022. The national team are each tested a minimum of three times a year out of competition to meet World Anti-Doping Authority (WADA) protocol.

What’s Next

After Chartier’s positive test and Sanders and Iden ending their coaching partnership after Hawaii, Von Berg – who won Ironman Texas last Saturday – is now Iden’s only remaining non-Norwegian coached athlete. Would he consider returning to coach Norwegian athletes only?

“It would be stupid if I didn’t [consider it],” he said. “As of now I am continuing, but I would be much more cautious of taking on athletes in the future. Now I’m in a full position in the federation, I don’t need to. Before I had a smaller position and was on contract, and I also did some long course [coaching] as I thought it was educational for my own career.

“I had been the head coach in youth and juniors for athletes in a club in Norway for many years, and I really enjoyed it. Right now, thinking about everything that has happened I feel I should go back to youth coaching because it’s just fun.”