Mark Allen's Nice Diaries: November 1982

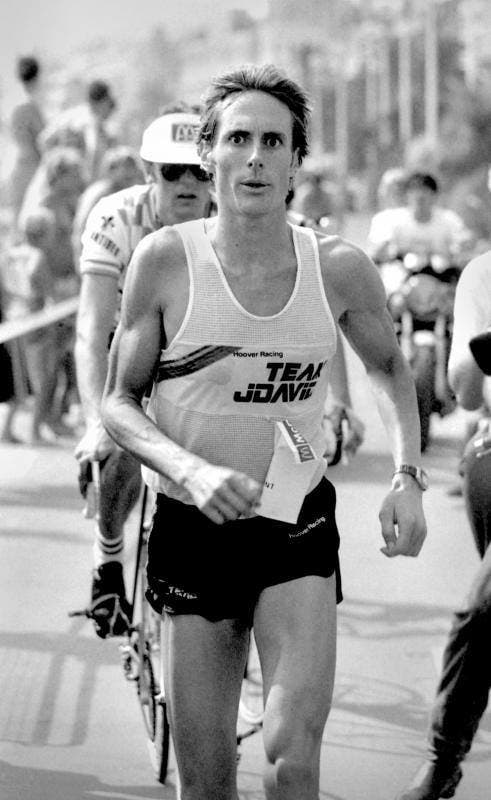

Mark Allen is surrounded by a spectacle as he races the inaugural Nice International Triathlon in 1982. (Photo: Christophe Croze/Nice Booklet)

On September 10, 2023, history will be made when professional and age-group men compete in the first-ever Ironman World Championship in Nice, France. But what you may not know is that Nice – known as the “birthplace of European long-course triathlon” – already has a storied history in our sport. In this three-part series, Mark Allen will revisit some of that history as he plays back the French highlights of his triathlon career.

It was 10:00 p.m. in Nice, France. I’d just arrived with other athletes who were on Team J. David, the first-ever professional triathlon team. The team was started by a California investment firm in 1982 and provided the first real financial support to athletes trying to make this sport their living. We were all on California time, so not one of us was tired. And what do triathletes do when they are not tired? Go train, of course.

We were there to race the Nice International Triathlon, a new event specifically created to capitalize on the huge buzz the sport had garnered after the dramatic collapse and crawl of Julie Moss months earlier at the 1982 Ironman World Championship. The world-class endurance challenge would feature a 1,500-meter swim, 100-kilometer bike leg, and a full 26.2 marathon. The unique middle-to-long distance format had attracted Ironman champions and ITU champions alike. It was the place to be.

I was 24 years old and in my first season as a professional triathlete. As one of the athletes invited to compete on the Cote d’Azur, I would be lining up along with the likes of Scott Tinley, Scott Molina and Kathleen McCartney – all past winners of the Ironman World Championship. Was I pinching myself? You bet I was.

Love at first sight

After confirming the hotel kitchen would be serving dinner until 11:00 p.m., we threw on our running shoes and headed out for a jog along the Promenade des Anglais. On one side of the road was the peace of the Mediterranean; on the other, the beautiful and historic cityscape of Nice. I was so excited to be there, experiencing Europe for the first time, that I drove everyone crazy.

“Look at that!” I called out every time I spotted something I hadn’t seen before (and there was much that I hadn’t seen before). “And that, and THAT!” Finally, they told me to just shut up and run.

I could have run forever that night, bathed in the warm streetlights of Nice. But Tinley and Molina were not about to miss a meal (a trademark of a true triathlete). We hurried back to our hotel, arriving just in time to get our first taste of French cuisine. Unfortunately, the hotel was part of a worldwide chain, so the food as I would learn later was not exactly true French fare. It had all the things you’d get back home: fish, chicken, potatoes and salad. The only real treat was the bread, which was 100% French. We gobbled that down. Yes, it was in the time before the fear of gluten had made you feel guilty for scarfing down as much of it as you could eat!

An American fish out of water

The next morning, the sun rose and it was undeniably cold. It was November, and the waters of the Mediterranean had become frigid. The alluring back peaks of the Alpes-Maritimes were covered in snow, drawing everyone’s eye with equal parts beauty and fear.

I dipped my feet into the water at the swim venue and shivered. Although I was told the water was 57 degrees, my years of surfing gave me the experience to know it was way colder. I had no idea how I was going to survive 20 minutes and 1,500 meters of swimming on race day. I’d be hypothermic without a doubt. (Do you remember that time before wetsuits? 1982 was indeed that time.)

Fortunately, the night before the race, we were told the swim would be cut to 500m. Someone was looking over me! I knew I could survive that. With that bit of news, we headed out for our pre-race dinner.

I only knew how to speak a couple of French words at that time, and certainly had no idea what all the things on the menu were. But one that sounded good, listed under “Salade,” was Fruits de Mer. I figured I’d start with that, and then point at one of the pastas for the main dish and hope it was a good choice. You know, fruit salad and pasta – lots of carbs.

If you know more than a couple of French words, you know that when the salad came, it was not a fruit salad. My plate was heaped with tentacles, shells and rubbery-looking things. My brain started to piece it all together and then the lightbulb went on. If translated word-for-word, it meant “fruits of the sea”. Note to self: the French language is poetic as much as it is literal.

A race to remember

On November 20, 1982, none of us knew we were making history at the Nice International Triathlon. All we knew was that the first task was to get out of the 500-meter swim with at least enough warmth left in our bodies to be able to pull on cycling tights and zip up an insulated long-sleeved jersey for the 100-kilometer ride.

Buoyed by the inspiring competition and even more inspiring landscape around me, I survived the swim. Shaking uncontrollably, but clear in my mind, I gave a thumbs-up to Scott Molina, who was just ahead of me in the changing room. Talking was out of the question, but at least that gesture signified we’d made it through what I thought was the most challenging part of the day.

I thought wrong. Riding a bike in Nice starts out pretty flat, but after a slow-bake upgrade along the River Var, we abruptly turned left and came face-to-face with the mountains. And they were breathtaking. Quaint, small, timeless roads, winding from ancient village to ancient village, had me remarking every mile just how lucky I was to be here. Yes, some climbs felt endless, but I felt like I was riding my own Tour de France, on roads unlike anything I had seen in the United States.

Quaint, small, timeless roads, winding from ancient village to ancient village, had me remarking every mile just how lucky I was to be here. Yes, some climbs felt endless, but I felt like I was riding my own Tour de France, on roads unlike anything I had seen in the United States.

And because I was unfamiliar with European roads, I was also unfamiliar with the 180-degree sharp hairpin turns on the descents. There was no way to practice for this back home. I just knew I had to take them conservatively and keep the rubber side down. A crash could easily end my race.

Unlike my race in Kona a month earlier, where I had to drop out just past the halfway point of the bike because my derailleur broke, the ride in Nice seemed to be seamless. I’d lost time on the leaders on the descents, but I didn’t care. I was in Nice! I was in Europe! This was a first-ever event, and I couldn’t stop looking around at how incredible the countryside was.

At the bottom of the descents, the sun had warmed just enough that I was starting to sweat. I stopped, took off my tights, and then kept going. (After the race, I would tell Molina that I stopped to do that. He just shook his head and sighed. “You stopped in the middle of the race to take off your tights?” he asked. “Well, yeah,” I responded. “I was getting hot.”)

Next up on the menu was a marathon run. Because of my DNF in Kona, I had never actually run 26.2 miles in my life. But I had seen everyone hobbling around Kona the day after the race, so I knew that good body maintenance was going to be key. My one goal as I headed out of T2 was to run as flat as I could, without any bouncing. I didn’t want to pound my legs. Keeping muscle breakdown to a minimum would be essential for completing that distance.

Just past the 10K marker on the run, I could see the leader. It was Scott Molina. He knew marathons and had a few under his belt already. But I was catching him! When I came up behind him, I could see he was bouncing…a lot. He was pounding his legs. So, what did I do? As I passed him, I gave him some free, unsolicited friendly advice: “You’re bouncing too much, try to run flatter.” That was the last time I gave Scott Molina unsolicited advice.

I went on to win that year, becoming the first long-course triathlon champion in Europe. The closing kilometers of the run leading to the finish line meant I got one more run down the Promenade des Anglais, just as I had done that first night. Only this time I was joined by thousands of fans, all cheering me on like I was their hometown hero, not some 24-year-old kid from the other side of the world. In the upcoming years, I’d make nine more trips to race in Nice, each one ending in victory. You may have seen or heard about some of those races – classic battles with the sport’s best. And as with all great victories, those wins came with intensely challenging moments that no one could see from the outside. I’ll save those stories for the next few episodes in the series. You’ll want to hear them, and I am sure you will be able to relate to each of them.

I’d been touched by the crowds on race day, and by the culture of Nice every day. I’d witnessed natural beauty that I knew I would remember forever. I’d passed through villages and walked streets that were hundreds of years old; places that I’m sure could have never predicted what Nice would bring to triathlon either!

I could not have predicted any of that as I stood atop the podium at the awards ceremony. But one thing I knew for sure: Nice had changed my life forever.

Stay tuned for more stories from Nice, as I share iconic battles and lessons learned.