Too Many Triathletes Are Getting This Part of Training Wrong

Triathlon has created an army of fit, tough, committed, focused athletes. But beneath the surface exists corrosive levels of fatigue and elevated injury rates. It’s all too common for triathletes to become stuck in a vortex of dysfunctional training, believing that success requires an ever-increasing commitment of time and energy. In an excerpt from his book, The Well-Built Triathlete, Coach Matt Dixon of purplepatch fitness reveals the “heretical” approach he uses to turn age-group triathletes into elite professionals.

Stress.

It’s one of those words that you likely hear or say almost daily. It’s usually loaded with negative connotations and reserved for the aspects of life that are filled with duress. But if we consider the role of stress in endurance training and performance, the word takes on an entirely different meaning.

Stress is your best friend when it comes to pursuing your athletic goals, but it can also easily become your worst enemy. Although we need stress to bring about adaptation, we need to pay very close attention to how much of it, and what kind, we bring into our lives.

The Epidemic of Underperforming

Too many highly motivated athletes in our sport never achieve the kind of results they seek from their very hard work. Many of our sport’s most committed athletes train long and hard and dedicate an enormous amount of energy to the pursuit of improved race performance. They become extremely, savagely, heroically fit, but they rarely see racing performance improve. They are fit, not fast. Triathlon has created an army of fit, tough, committed, focused athletes. But if we look beneath the surface, we are likely to find corrosive levels of fatigue and elevated injury rates. Sometimes the athlete who appears to embody all that is healthy is actually unhealthy—on the verge of a systemic or metabolic breakdown. It’s all too common for triathletes to find themselves stuck in a vortex of dysfunctional training, believing that the pursuit of success requires an ever-increasing commitment of time and energy. Why does this happen so frequently?

Triathlon is a sport that attracts very committed individuals who are typically high performers in other areas of their life. Part of the problem is the culture itself: Dedicated (dare I say obsessed) athletes are central to the fabric of triathlon. It’s a sport that presents several unique challenges, comprising three individual sports blended to make one event. The challenge of training for three disciplines instead of one is easily apparent and is an instant catalyst for many of triathlon’s most subtle and pervasive problems. Thus, given the character of the athletes drawn to the sport and the sport’s unique structure, it’s tempting to dismiss what I call problems as inevitable—but there’s more to the story.

Unfortunately, it is not simply the nature of the sport itself that leaves so many participants underperforming—in training, racing and life—relative to their commitment level and goals. Often the way that the athletes approach their training program delivers an accumulation of too much overall stress and too many overall stressors. In turn, the training generates chronically elevated levels of fatigue and stagnant or declining performance.

If your goal is to win the Hawaii Ironman World Championship, everyone would agree that you will need to do a very high amount of training. With this in mind, if I was to ask last year’s champions if, despite their wins, they wished they had managed to get in even more training, I am sure that they would look at me as if I were crazy. They know that they did precisely enough training to win—no more, no less. They may recognize an element of luck in the mix, but none would consider his or her preparation insufficient. But more to the point, they did not overdo it. Had they done so, they would not have performed so well. They did the amount of training their bodies could handle and no more. This is a lesson that triathletes struggle to internalize. Instead, we fixate on the staggering training volume that most world-champion professional triathletes endure and conclude that we should train that much in order to optimize our performance. Of course many of us are not aiming to win the overall championship in Kona, but nearly all of us are looking to improve.

The success of your training plan should not be judged by the number of hours you have accumulated. Rather, it should be judged by the level of adaptation that your hours of training have delivered.

If you spend lots of time adding up weekly training hours and monthly totals, it’s time to put your pen down. If your lens on training success is built around a simple accumulation of hours, you cannot be maximizing your performance potential. While training volume is important, it is a derivative of a sensible training plan, not the objective. Training volume as the metric of projected success is nearly immaterial. There. I said it. I am officially, publicly, irretrievably a heretic.

What Is Training Stress?

Training stress is any disturbance, triggered by physical activity, of an athlete’s overall metabolic and physiological state.

Your training is the necessary stress that should elicit positive physiological adaptations to make you stronger, fitter and more powerful. If your training approach is appropriate, the stress of training will facilitate positive change. If your training approach is not appropriate, then negative changes (or unwanted adaptations) can occur.

Optimizing Stress and Adaptation

As a training athlete, your goal should be to maximize specific stress while staying in a positive state of adaptation. This sounds simple enough, and this alone could guide you to make sound decisions throughout your training process. But it’s all too easy for highly motivated athletes to lose a sense of logic and fall prey to emotional and fear-based decisions when assessing their training needs. Too often endurance athletes fall into the trap of judging training success by how many hours they can accumulate in a week, regardless of whether their training is actually providing positive change. Let’s give this a further twist and think about it, from the opposite side: Your goal, as an endurance athlete, is to do the absolute minimum training necessary to achieve your goals.

I know it sounds radical to suggest that you do the least amount of training possible to achieve your goals, but we’ve established that it is not the actual amount of training stress that counts. Rather, it is the relationship between stress and recovery that matters. This statement is not exclusive to training: Put this way, you can see why understanding all of the stress in your life is so important. As an athlete, you can and should differentiate between two distinct stressors:

• Training stress: Specific, applied, intentional stressors that are critical to facilitate improved performance in your sport

• Nontraining stress: Variable, unpredictable, uncontrolled stressors that you are forced to deal with on a daily basis but are not specific to improved performance in your sport

While many amateurs are highly motivated and have great passion for their sport, most would agree that the goal is to maximize sporting performance within the restrictions imposed by the need to maintain a balanced and successful life. After all, if you win your local Olympic-distance triathlon but get fired, or your spouse leaves you, or your house is repossessed, it would be hard to argue that the win represents “success.” By necessity, your outlook as an amateur is a little more nuanced. Thus, for most of us, success can be more broadly defined as improving in the sport, performing at work, thriving socially, and nurturing positive relationships (with spouse, partner, children or friends). With this outlook, the goal of the amateur triathlete should be to maximize training load as one part of a vibrant, passionate and engaged life. I refer to the full picture of your life inside and outside sport as your global stress environment. The amount of training you undertake needs to fit within the constraints of that environment in order for you to be successful.

Quantifying Stress

Your training causes hormonal, cardiovascular and musculoskeletal stress. The trick is to apply enough training stress to create positive change but not so much that you accumulate too much fatigue or get injured. So how do you go about this?

Nontraining stressors (work, family, relationships, environment, travel, finances and so on) don’t provide much (if any) musculoskeletal or cardiovascular stress, but they certainly accumulate and inflict a great deal of hormonal stress on your body (Figure 2.1, above). This is an incredibly important point, so let’s take a moment to explore it in more detail.

First, the endocrine system is massively, mind-bendingly complicated. As much as sport science has taught us about hormones, and as much as we are beginning to understand how hormones regulate everything in our body—including our response to stress—we really don’t know all that much. Rather than try to cover what thousands of research papers have failed to explain, I’ll focus here on the salient points.

First, simplistically, there are two main hormones we can think about when it comes to stress response: testosterone (T) and cortisol (C). These two hormones work in tandem to create the “fight-or-flight” response to stress. Again simplistically, elevated testosterone is associated with “fight,” and elevated cortisol is associated with “flight.” But both are triggered by any stress event; what matters is the T:C ratio rather than absolute levels. A stable ratio indicates a high capacity for stress absorption and adaption. Elevated testosterone is better than elevated cortisol, but it has its own problems. This is one of the reasons that hormone replacement therapy is so effective for masters athletes: It resets the T:C ratio back to where it was when the athlete was young, resilient and capable of handling an enormous training load.

The challenge is that no individual athlete has the resources to track and monitor dynamic hormone levels on a daily basis. This is why it is so important to develop a recovery awareness relative to your global stress load and to understand what life events can disturb these hormone ratios.

You might not associate the stress of a job interview or a poor night’s sleep tending to a baby with that of performing hard hill-running repetitions, but all three events create a massive amount of hormonal stress and strain on the system. Although our bodies are incredibly smart, they don’t do a great job of differentiating the different sources of stress that suppress our hormonal systems. For the endocrine system, a fight with your boss might have the same effect as toughing it out through a really hard interval session. This understanding reveals the importance of acknowledging the accumulation of stress that we all face in our daily lives. It should also lead you to the realization that the application of training stress needs to be carefully thought out in terms of overall training load and in conjunction with your global stress environment.

Pillars to Support (or Destroy) Adaptation

There is a way to improve your overall metabolic health and offset a lot of the negative stress provided by the accumulation of life stress as well as stress provided by training. Recovery (sleep, rest, and recovery) and nutrition (nutrition, hydration, and fueling) can be your most consistent performance enablers. Of course, recovery and nutrition are no panacea—as is the case with stress and adaptation, the very same things that can lead to stress reduction, mitigation, and balance can quickly become the most destructive negative stressors that you have to cope with. In order to get these right, you must calibrate timing and quantity, and, given the unpredictable nature of life and training, it must be an ongoing effort. Ignore them and you will experience negative consequences—maybe not today, and maybe not tomorrow, but eventually.

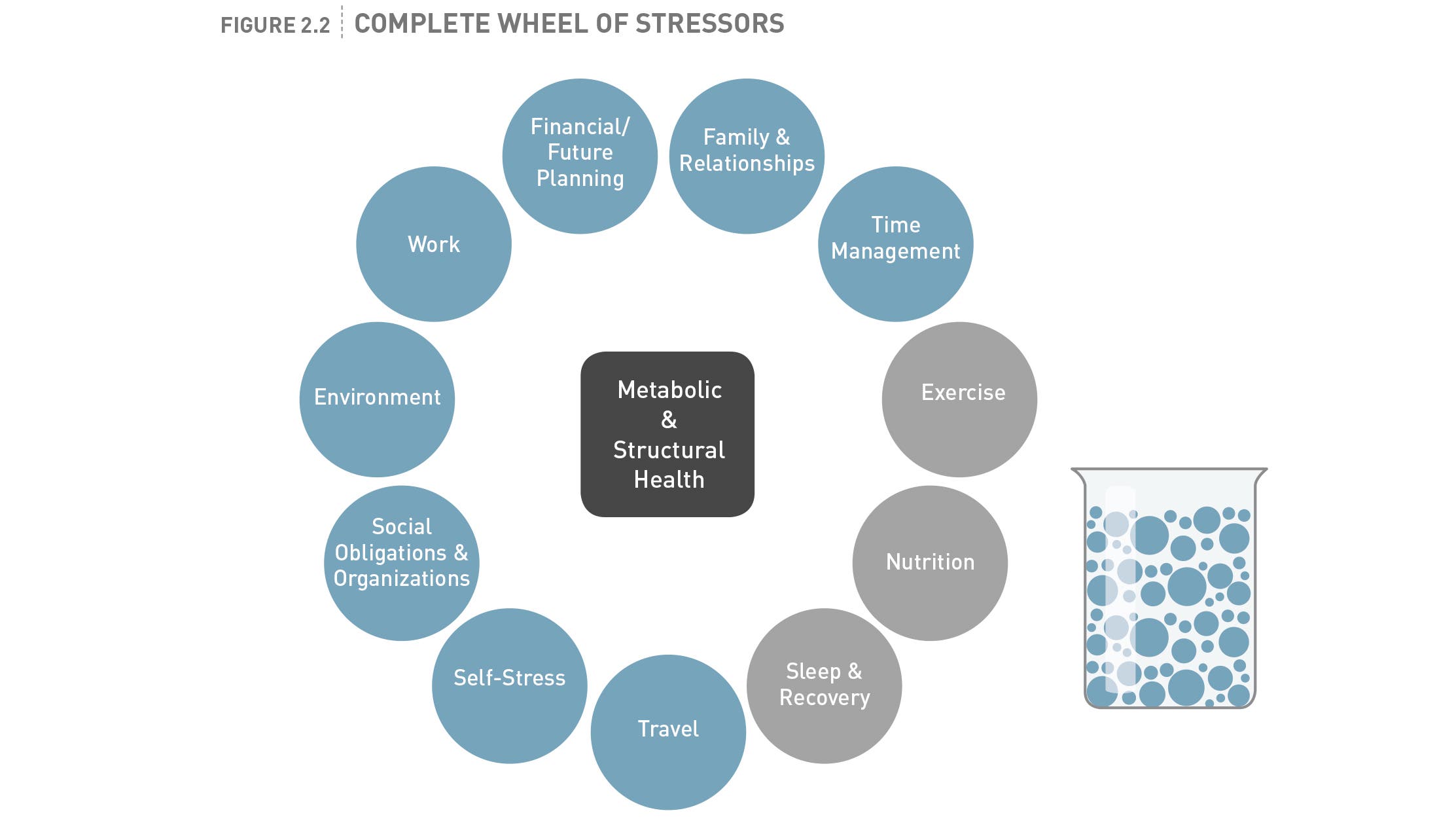

When we consider training integration, specifically as it relates to recovery and nutrition, we can complete the whole picture: the “wheel of stressors” that should be considered in setting up our training life (Figure 2.2, above).

The success of your training plan should not be judged by the number of hours you have accumulated. Rather, it should be judged by the level of adaptation that your hours of training have delivered.

Uncovering Your Potential for Positive Adaptation

Become Aware of How You Respond to Stress

Before you dive into planning a detailed integration of your training schedule and the other parts of your life, you should consider another important element of stress and training: Every athlete (and person) responds differently to stress. How you will respond to the stress of an interview or the pressure of endless nights of limited sleep is highly individual. Over time you might even find that you respond differently to identical stress events at different times. It’s possible for different athletes to respond identically to similar stress events or to respond differently to identical stress events.

In other words, an athlete’s stress response varies over time and with circumstances.

Exactly the same kinds of variations affect how you will respond to training load and type, which is why it is so important to avoid the temptation of following the training regimen of a top professional triathlete. I work with many athletes who are highly resilient—they can handle enormous amounts of training before succumbing to fatigue or signs of nonadaptation. I also work with athletes with similar life stressors and race results who are much less resilient under a similar training load. These athletes are more fragile— they can still have every chance for success, but they must be coached very differently.

A great example of this type of situation is two very different athletes who experienced similar success under my guidance. Linsey Corbin (whom I no longer coach) and Meredith Kessler are both multiple Ironman champions and have raced head to head many times. A few years ago they both toed the line at Ironman Coeur d’Alene, doing battle throughout the race and finishing in first and second place with only a couple of minutes between them. They were both a long way ahead of the rest of their competition.

While it was a lovely day for both them and purplepatch, the point is that the journey of training they took to get there could not have been more different. At the time, Meredith had transitioned from full-time work into the life of a full-time pro and had years of endurance-based training behind her. She was highly resilient and was embracing the newfound time she had on her hands. She was responding very well to a high-load training plan, with only periodic small bursts of recovery needed to keep her fresh. She was doing a lot more than she had previously and was maintaining positive adaptations.

In contrast, Linsey was coming off a high-load training approach that had left her with various ailments and fatigue. Her situation was very different, as she had a greater tendency to accumulate fatigue and get niggling aches and pains. For her to be successful at this time (she has since evolved back to being able to complete greater load), she needed to integrate much more recuperation and recovery into her training. Her focus was on consistency and avoiding too much fatigue. She was completing fewer hours with more recovery and also with more focus on intensity in key sessions.

If I had flipped their plans, their results would have been below par or might even have resulted in injury. This type of difference in approach is worth considering in your own preparation.

Develop a New View of Training Stress

During workouts and in the hours that follow, you are likely to experience acute fatigue. Although it’s perfectly normal, I would even venture to say that acute fatigue is a necessary part of training. Feeling tired during or after a workout does not mean you should pull the plug on that session or schedule multiple days of recovery. This is anticipated stress. We expect to feel fatigue during and after a session.

That said, appropriate training should not result in massive trauma that leaves you very sore and with debilitating fatigue. Any time a single session leaves you with extremely sore or tight muscles, or the inability to recuperate and train the following day, that session was likely too intense relative to your current fitness or level of accumulated fatigue. I call this outcome unanticipated acute fatigue, and it is a sign that the session’s stress was too great for your body to effectively respond in a positive manner. Of course, fatigue is always a tough element to balance, and only wisdom and experience, as well as a little smart planning, can truly enable predictable outcomes.

When you string together multiple days or weeks of training, you are likely to experience an element of accumulated fatigue. This, again, is absolutely normal but is worthy of some consideration so that you can tell the good from the bad. Let’s say you head away to a training camp and embark on multiple days in a row of extended workouts, with more workouts in a day than is typical. You will almost certainly accumulate fatigue, but the keys that this is anticipated accumulated fatigue. It is a part of the plan and does not call for any action. In fact, it is likely important and highly beneficial to push on with this fatigue accumulation, as you are using the multiple sessions and days to deliver a large training stress. Assuming that recovery will occur soon, this anticipated fatigue can yield very positive results. One of the primary reasons why positive adaptation is possible in this scenario is because at a training camp, you are likely to enjoy minimal nontraining stress.

This is very different than unanticipated accumulation of fatigue, in which you experience a slow buildup of residual fatigue to the point that the body falls into a state of nonadaptation. When this occurs, it doesn’t mean you are “overtrained,” a term that is thrown around far too loosely in endurance circles, but it does mean that ongoing application of training stress will not yield positive results. In other words, if you choose to carry on training hard when in this state, you will be unable to adapt to the training stress.

It is critical that you understand and monitor this type of unanticipated stressand fatigue accumulation. When you reach a nonadaptive state, it is an impossible situation because it is the point where injury, illness or longer-term fatigue is right around the corner. A smart athlete is able to train up to this line, then intuitively respond to the need to back off and recuperate. Once time is allowed for restoration and positive adaptation, it’s possible to push hard again. Unfortunately, most of us are not intuitive when it comes to the warning signs of unanticipated accumulation of fatigue. Let’s explore the typical signs and symptoms that your body has accumulated too much fatigue through stress.

Sleep

• Broken sleep patterns most nights

• Waking up with night sweats

• Feeling very tired in the afternoon but wide awake during the middle of the night

Performance

• High perceived effort with suppressed power, pace and heart rate relative to expectations

• Inconsistent or poor training or race performance despite good fitness

• Inability to reach higher-intensity speed or power intervals despite good fitness

• Inability to recover from single workouts

• A string of poor results despite seemingly good preparation

Body and appetite

• Unusually sore or tender muscles

• Drastic changes in body composition (inability to lose fat or sudden weight gain or loss)

• Frequent sickness such as colds, sore throats and fevers

• Inability to get healthy following sickness

• Changes in appetite

• Blood values red-flags: declining iron, vitamin D, blood-profile disruptions

Mindset

• Declining ambition or motivation to train

• Lack of enjoyment or fulfillment in training

• Feeling of sorrow or depression

• Apathy about goals or upcoming races

If you ever experience many of these symptoms, you are likely in a state of nonadaptation, and you must allow rest and recuperation. This condition is obviously a warning sign that your training approach has flaws, but in my experience these flaws are not limited to the number of hours you are actually training. Poor or inadequate sleep, recovery, nutrition, fueling and hydration all contribute to an accumulation of too much stress. Don’t expect to get through your training year without falling toward this state once or twice. It is the awareness of the situation and the actions that you take when it does start to take hold that will allow you to forge through without massive disruption or other negative consequences.

New Goals for Endurance Training

What does all this really mean in your training life? Let me suggest an approach to training that might change your perspective on it for the rest of your life:

Your goal for your training program should be to achieve great consistency of specific and effective training by minimizing life stressors and maximizing your training load while remaining in a state that allows for steady, positive adaptation. If your life stressors accumulate to the point where they become an overwhelming force in your life, you will have to recalibrate your training load in order to remain consistent (and healthy).

Put another way (and very simplistically): You should be training the least amount possible to achieve your goals.

I cannot tell you how many times I have been asked by athletes, other coaches or journalists about the number of hours of training necessary to perform well in triathlons. “How many hours do I need to train for an Ironman?” “How many hours a week do your professionals train?” “If I can squeeze in more hours of training, should I?” All of these “how much” or “how many” questions are the wrong things to be asking and, in my mind, are irrelevant to setting up a smart program.

To be honest, I rarely consider total training hours as a barometer for success; in fact, I seldom even add up how many hours a week my athletes actually train. Instead, I engineer the key sessions that I feel need to occur, then surround them with other supporting sessions that help recovery or preparation or work on another element of endurance performance. The framework of the week is built around two linked concepts: What needs to get done? When can the athlete accomplish it?

Once the framework of the training week is mapped, I also need to consider (especially for busy amateurs) if there is time in the week to allow recuperation and downtime. Rather than compressing workouts into every possible window of time in the day, we treat sleep, recovery and rejuvenation as a part of the program as much as swimming, cycling and running. This level of recovery intentionality forces the athletes I coach to look at recovery in the same way that they look at training: something that must be accomplished in order for them to consider their training plans successfully executed. If they don’t execute the assigned recovery, they have failed. Brutal but simple.

Excerpt from The Well-Built Triathlete: Turning Potential into Performance, by coach Matt Dixon courtesy of VeloPress (velopress.com).