Most Runners Overstride—Here’s How to Stop It

“Running Rewired” author Jay Dicharry explains what it means to be quad-heavy and glute-light.

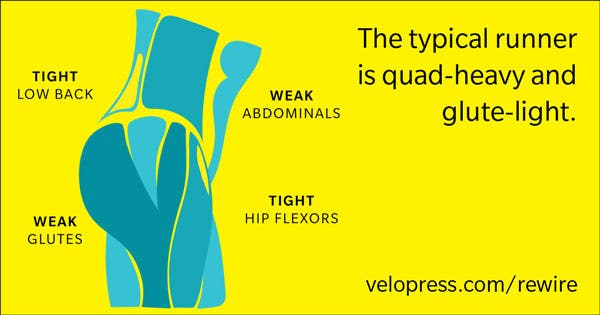

When you run, especially as your speed increases, more and more oomph needs to come from the muscles that extend the hips. But it’s likely that years of overstriding have wired your muscle memory to favor the quads and neglect the glutes. Said simply, the typical runner is quad-heavy and glute-light.

Most runners overstride. The lab data I’ve collected over a decade reveals why—the vast majority of runners don’t know how to fully use the muscles in their backside. It would be much easier if muscle control was balanced around the body, but the reality is most people are out of balance, a problem that is not exclusive to running. Dr. Vladimir Janda, a pioneer in muscular therapy, coined the term “lower crossed syndrome” to describe the imbalance that occurs when the hip flexors, quads, and low back muscles are tight and overused, and the deep core and glute max are asleep at the wheel.

Earlier chapters of “Running Rewired” reveal that the best way to inhibit the muscles around your hips is to screw up your posture. And then there’s the issue of tight hips. If those muscles are tight, your hip won’t have full extension to both sides of your pelvis. This imbalance isn’t a running problem; it’s a body problem. But if this body problem isn’t corrected, you’ll never be able to correct your stride. About 80 percent of runners will need to do a lot of hip flexor stretches to improve this.

Your quads are big muscles, capable of producing a huge amount of force. No matter what your running form, you need your quads to show up ready to work. But muscles don’t act alone, and we certainly don’t want the quads to carry the torch when running. Changing your dominant muscles for moving and running is critical to improving joint health and performance.

The Problem with Quad Dependency

Being overly reliant on your quads creates three big problems.

First, it can wreck your knees. Nearly every study on running injuries ranks patella-femoral pain in the top three injuries ailing runners. Your patella, or kneecap, is basically a pulley for your quad. When you overstride, the torque or mechanical load on the knee is greater. The quad has to work harder, creating more shear across the surface of the patella, which isn’t the best thing for the long-term health of the cartilage underneath it. Changing your muscle dominance will reduce stress on the knee.

Second, there are some performance implications for our bias toward the quads. Your quad has a greater percentage of fast-twitch fibers. So for a given running pace, your quads will be working closer to peak capacity and enter into a fatigued, or an acidic state, sooner. When the muscle gets too acidic, the pH level drops and the muscle can’t contract and relax as well, so you end up hitting the wall. Since the glute has more slow-twitch fibers, it produces smaller amounts of acidic waste products and can last longer before building up a lot of waste. This means you can drill the pace a bit harder and longer without falling apart.

Finally, your quads simply can’t match the total body control your glutes are capable of setting in motion.

Your glute max has three primary functions, all of which benefit your running. I go into detail on the important role of the glutes in Chapter 7 of “Running Rewired”, but let’s summarize here:

1. The glute max is an incredibly powerful, fatigue-resistant muscle that drives your hip from the front of your body to the back. Your quads do the opposite.

2. Your glute max is also your primary hip external rotator; in other words, the glute max prevents your knees from crashing in when you run.

3. Your glute max plays a huge role in postural control; if your glute isn’t firing properly, your torso will pitch forward and cause you to overstride. Overstriding means very high loading rates with each step, putting the body under more stress with every stride.

This stuff matters.

Three Glute-Activating Exercises

- Hold a kettlebell or dumbbell in one hand, and let it hang down at your side.

- Keep your shoulder blades packed down along your ribs and actively counter your tendency to lean away from the asymmetric load.

- Hold yourself completely vertical as you walk for 30 seconds.

- Do 4 30-second carries.

- Hold a kettlebell tight to your chest in both hands with shoulder blades spread wide and locked down on the back. Your feet should be slightly more than shoulder-width apart.

- Staying centered over your feet, sink your hips back and down in a squat until your elbows touch your thighs.

- Keeping a neutral spine, drive back up to standing position.

- Do 3 sets of 8 reps.

3. Landmine Single-Leg Deadlift

- Position one end of a 45-pound Olympic bar on the floor in the corner to anchor it.

- With the free end of the bar perpendicular to your body, stand on your outside leg and hold the bar in the opposite hand; let your arm hang down straight. Raise your free arm out to the side for balance if needed.

- Hinge your hips back while keeping your spine completely straight and lower the bar while raising your back leg behind you.

- Push your hips forward into the bar to return to the starting position.

- Face the opposite direction to work the other side.

- Do 3 sets of 8 reps on each leg.

[velopress cta=”Shop now” align=”center” title=”Buy the Book”]