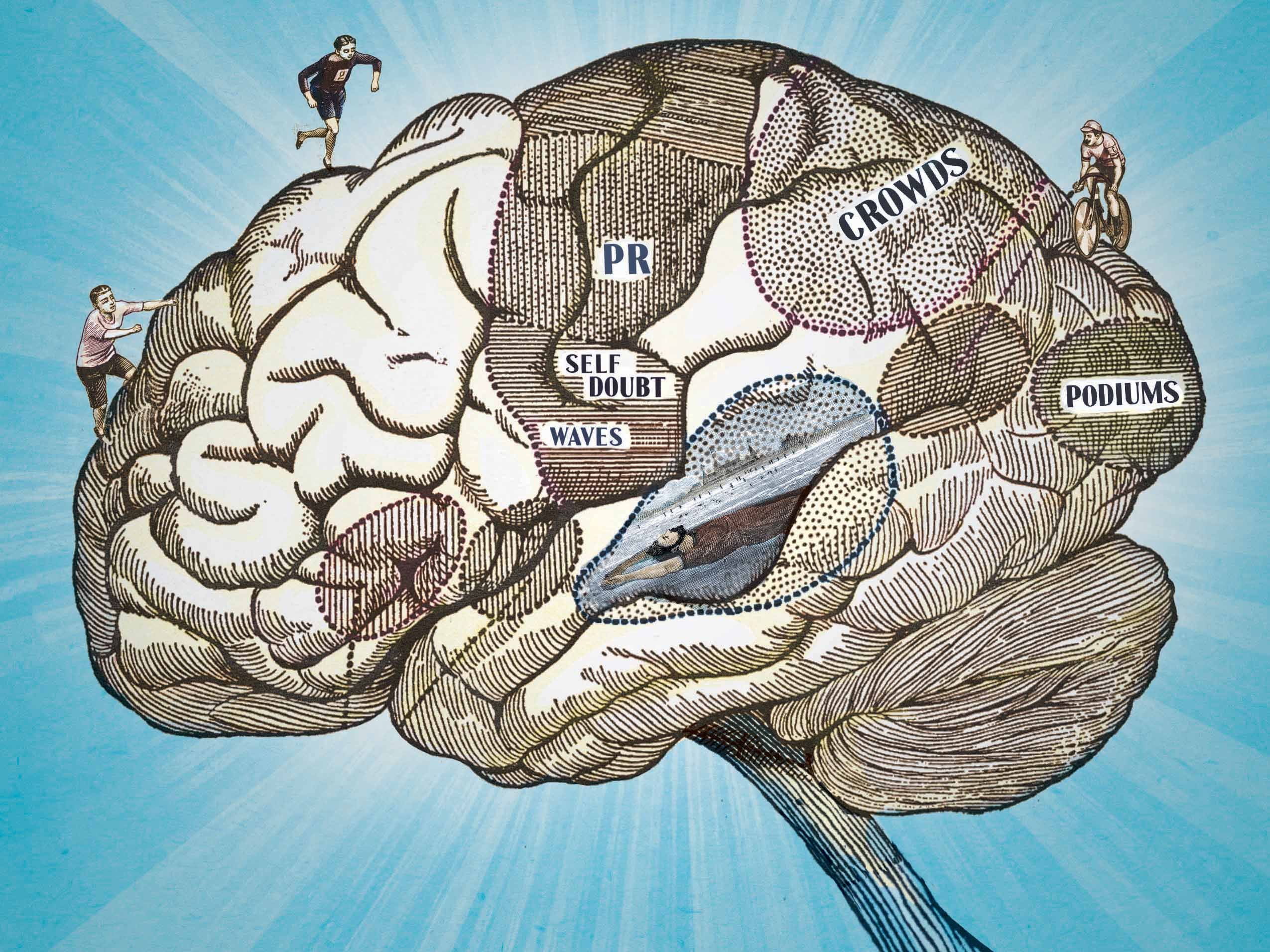

Sports Psychology Tips For Triathletes

Illustration by Leigh Guldig.

It’s 2012, half an hour before the pro start at Ironman Frankfurt. The crowd is buzzing. The pros are jittery. The pressure’s on; this is one of the last opportunities of the year to earn Kona qualifying points.

“Flying Dutch girl” Yvonne Van Vlerken needs to perform well here to get to Hawaii. She placed fourth in Frankfurt last year. In fact, since she blasted onto the long-course tri scene in 2007 with a record-setting win at Quelle Challenge Roth, she’s been on fire, dominating 70.3 and iron-distance events alike. But with all of those wins comes pressure. The pressure to win again. To be the best. To do even better than last time. All of that pressure bubbles up in her stomach and explodes; it’s minutes before Ironman Frankfurt and Yvonne Van Vlerken is puking.

“I was so sick from being nervous. I couldn’t cope with the pressure,” she recalls. After that rocky start, she DNFed 10K through the run due to injury, her Kona dreams dashed.

Van Vlerken’s then-boyfriend realized she was struggling before races, and introduced her to the man who would turn everything around, and give her back the peace and positive excitement with which she used to compete: Arno Gantner, a sports psychologist. Van Vlerken calls him her mental coach.

“I think the mental part is so much more important than people think,” Van Vlerken says. “I think it’s very underestimated.”

If nutrition is triathlon’s fourth leg, brain training is a close fifth. The U.S. Olympic Committee currently employs five full-time sports psychologists, a clear endorsement of mental preparation.

“It’s nothing spooky,” Van Vlerken says. “Other sports have it, so why shouldn’t a triathlete?”

Even if you’re not plagued by pre-race upchucks, working on your mental game can not only make training and racing more pleasurable, but also make you a faster, stronger athlete. We asked three top sports psychologists—and some seasoned pros—to share tips to get you rolling toward your next PR.

Your Mental Coaches

Dr. Peter Haberl

U.S. Olympic Committee sports psychologist

Dr. Chris Carr

Sport and performance psychologist at St. Vincent

Sports Performance in Indianapolis

Dr. Barbara Walker

Founder and performance psychologist at Cincinnati’s

Center for Human Performance

RELATED: The Six Habits Of Highly Effective Triathletes

Problem 1: Staying motivated while training

Sticking to a training plan isn’t always easy, especially if your race is several months away.

Solved: “Start by seeing what role the sport plays in your life, what you get out of it, and what got you started in the first place,” Haberl says. Often, athletes start competing for fun, then begin to focus on achieving a certain time or weight. “Figure out a way to tie it back to that initial source of joy.”

Carr stresses the importance of learning the difference between outcome goals, like finishing a race in a certain time or place, and process goals, the goals you establish along the way. “The more important goal is: What do you need to do today, or this week?” he says. “Address staleness or lack of motivation by establishing daily and weekly short-term goals.” That will make you feel accomplished every day you train—not just after a stellar race.

RELATED: Motivation Tips From A Fellow Age-Grouper

Problem 2: Avoiding burnout

Feeling particularly unmotivated? Perhaps you’re fried on tri.

Solved: “When someone gets stale in their training, they often don’t get enough rest and recovery,” Carr says. “They’re also too focused on outcome goals instead of process goals.” When that happens, doubts, fears and concerns can creep in during training days when you feel far from your outcome goals. So, again, don’t forget to set daily and weekly objectives.

And if you still reach the point of no return, a break might be in order. “When you’re burned out, the first thing you have to do is take time away from the sport,” Haberl says. “Once you’ve had a break, then it’s time to reassess what you expect to get out of the sport, and how you see yourself through triathlon.”

RELATED: Avoid Late-Season Burnout

Problem 3: Race anxiety

Worrying about achieving a goal time can be paralyzing. So can stressing about flat tires, mechanicals, goggle glitches, crashing, bonking, hurting, etc.

Solved: “You want to make that [mental] transition in the race to be subconscious, where you’re clicking into autopilot,” Carr says.

Walker recommends sleeping well a few nights before race day. “Assume you’re not going to get a good night’s sleep the night before the race, and then don’t worry about it, because you know you have a bit in the bank,” she says. Also, make sure all of your gear and nutrition is ready to go the night before. “Then make sure you give yourself extra time to get to the race. As soon as you rush, you’ll trigger that anxiety response,” Walker says. “Breathe through it.”

RELATED – Psych Out: Dealing With Race-Day Anxiety

Problem 4: Swim anxiety

It’s entirely possible to get a heel to the face. Enough said.

Solved: “Recognize that this is a contact sport. Know ahead of time that you’ll need to be mentally ready for battle,” Walker says. Long before your race, start to visualize yourself dealing with knocked-off goggles, a jab in the back, an elbow to the ribs—mentally work through your worst swim nightmares, so if they pop up on race day, you’ll know how to cope.

Also, Walker says, pay attention to your body temperature. “Sometimes, when you’re cold, it feels like you’re anxious,” she says, so you’ll start to get anxious, because you think you’re anxious, but really you were just cold. It’s a vicious cycle.

Problem 5: Maintaining focus while racing

Did my mom come to cheer? Is that my mom? Squirrel!

Solved: “The first thing you want to do is make a plan for the race,” Haberl says. Part of that plan should focus on a specific point in the race that you think will be difficult. “You want to be aware of the specific thoughts that undermine confidence.” Staying focused will help with confidence, Haberl says, “because once you stop paying attention to what’s going on in the race, you stop paying attention to your form. Paying attention to your form will be much more conducive to racing well than having a debate in your head.”

Also, try using cue words. “When you’re racing, and you start to feel something that’s distracting, or feel confidence fade, you want to have the ability to make a mental transition to get you back into your flow,” Carr says. “In other words, you don’t want to completely get off of the interstate at an exit; you want to get off at a rest stop, and come right back on.” Cues—words or mantras that keep you focused and present—can help. It’s as simple as repeating a few bon mots to yourself whenever you need them. You might tell yourself, “just chill,” on the swim, or “strong and smooth” on the bike to induce optimal cadence and power.

Pro Tip: Cue Words

Van Vlerken recently tattooed the word “gratitude” on her left wrist to remind her of how lucky she is to be racing. She’s also placed run course signs broadcasting the same word for inspiration.

RELATED: 9 Tools For Boosting Mental Toughness

Problem 6: Keeping up race-day confidence

I must be last after that terrible swim. My legs hurt more than they should. I dropped a Gu—I’m going to bonk!

Solved: Stay positive. “If you put negative thoughts in your mind, then they’re more likely to be predictive and accurate,” Carr says. Walker agrees. “Every time a negative thought enters your head, you’ll contract your muscle fibers, and you won’t have the same body out there as you did in training,” she says.

Whenever a negative thought begins to creep in, replace it with a positive one. Got a flat? That’s OK, you’re a whiz at fixing flats! A few other strategies: “Remind yourself of the body parts that feel good,” Walker says. Or try counting your steps. And just as you might during a big workout, break the race into pieces, then remind yourself you’ll soon be moving on to the next discipline.

Pro Tip: Positive Self-Talk

“I remember specific training sessions when I had an awesome day,” says Thomas, who added a sports psychologist to his training arsenal in 2013. “This year during Wildflower, I used ‘4:38,’ the time of the mile I ran at the end of a big interval long run. During the entire run, I told myself, ‘Nobody can do that!’”

RELATED: 5 Little Ways To Shave Big Time In Your Next Triathlon

Problem 7: Disappointment

You trained for an entire year and didn’t hit your race goals.

Solved: “There’s no such thing as a bad race,” Haberl says—just a learning opportunity. “Analyze the point in the race where you perhaps lost focus, you lost drive, you lost motivation, and learn from those moments.”

Walker once worked with a triathlete who had always dreamed of going to Hawaii. When he finally raced in Kona, he bonked so badly on the run that he couldn’t finish. Afterward, “he was literally clinically depressed, because he worked so hard to get to that place,” Walker says. How to recover from a similarly big upset? “Make sure you’re talking to other people, finding support. Then go ahead and set that next goal.”

Remember, Carr says, “One of the beauties of sport is that, in the effort itself, you’ve accomplished a lot of great goals. The mere fact that you’re competing is a success in itself.”

RELATED – Chris McCormack: Embrace The Suck

Problem 8: Injury

Being sidelined can be mentally taxing, particularly when social activities revolve around training—and endorphin levels, race plans and your fitness all take a hit.

Solved: Haberl recommends looking at examples of other athletes who have had similar injuries, and how they coped. Gnarly bike crash? See: Meredith Kessler. Chronic back pain? See: Craig Alexander.

“Bring the same focus and the same intensity to your rehab work that prior to the injury you would have brought to your training,” Haberl says. That includes setting goals adjusted to your injury, Carr adds, “without feeling failure or a negative self-concept because of an uncontrollable circumstance.”

RELATED: Chris McCormack’s Advice On Dealing With Injury

Problem 9: Equipment envy

If only your bike were 2 pounds lighter, you’d be so much faster.

Solved: Again, cut it out with the negative self-talk. “Do you think anyone in the history of triathlon has ridden a fast bike split on a slower bike?” Carr asks. “Well, it’s because they didn’t perceive themselves negatively on that piece of equipment.” Need proof? MarkAllenOnline co-founder Luis Vargas once clocked a 4:56 in Kona on a steel-framed beast that weighed 23 pounds.