Pain is a Message, and We're Horrible at Listening to it

(Photo: Eric Alonso/Getty Images)

Every triathlete knows what it means to be uncomfortable. It’s a hallmark of endurance sports, and for some athletes, discomfort is the very thing that keeps them coming back day after day. But how much discomfort is too much? The harder you push, the more likely you’ll find yourself limping into the proverbial “pain cave.” Though some in the sport like to romanticize the notion of “pushing through the pain,” the reality is that pain is a message, and endurance athletes are notoriously horrible at listening to it.

What is pain, exactly, and how can endurance athletes learn to cope better with it? That’s exactly what researchers are trying to discover.

The Genetics of Pain

Professor Jeffry Mogil, a Canadian neuroscientist who’s long investigated the genetics of pain in his lab at McGill University in Montreal, is one of them. For some 25 years, he’s been unraveling the inner workings of pain, and has come away with more questions than answers.

“Pain is the number one human health problem by a number of metrics,” says Mogil. “But we don’t know much about it.” That’s because pain is fundamentally subjective. With cancer, for example, you can measure tumor size and location, and that gives you a pretty good idea of the extent of the problem. That’s not the case with pain, where there’s no tangible, objective marker that can be used to quantify the scope or severity.

“Not only do I not know how much pain you have, I don’t even know that you’re capable of feeling pain,” says Mogil. “It’s completely subjective, which is why it’s such a difficult problem to treat, especially when pain becomes chronic.”

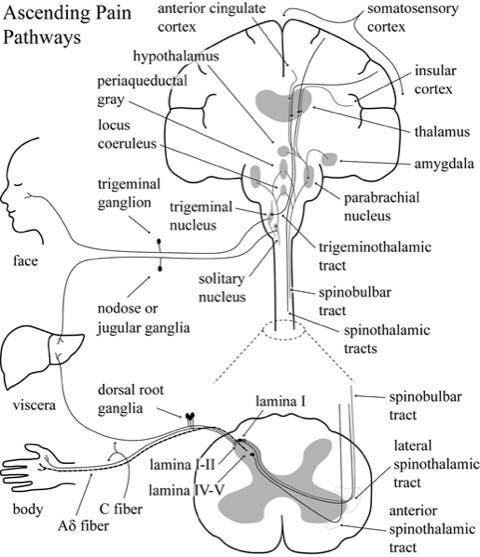

But scientists do have some understanding of how pain works. For starters, we know the brain plays a large role. While the triggering event may have occurred in some other distant location of the body, the actual perception of pain happens in the brain, which, according to Mogil, is “the most complex object in the universe that we know.”

“In general terms, there are specialized nerve cells called nociceptors, whose job it is to turn energy from the environment into a neural signal that our brain can decode,” says Mogil. Nociceptors receive signals about heat, cold, mechanical pressure, or certain chemicals – such as the inflammatory chemicals that are released in response to an infection or trauma – that the body needs to be aware of because of the potential for injury when in contact with such stimuli. When a nociceptor senses the triggering stimuli, an impulse races into the brain where it bounces around until the brain comprehends what information is being relayed. This process can be observed on functional MRI scans. “So we can tell you where it happens, but how it happens, that’s what’s called the hard problem of consciousness,” says Mogil.

Beyond that? “We’re swimming in a sea of ignorance here,” Mogil admits.

Much of Mogil’s early work focused on trying to pinpoint the genetics of pain and perhaps isolate a single master pain gene that could be tinkered with to help people with chronic pain conditions. But this opened up the paradox of neuroscience research: the more we learn about the brain, the less we actually know.

“Twenty-five years ago, those of us who were doing this research thought we were looking for 5 or 10, maybe 20 genes,” he says. “But now, the latest estimate into how many pain genes there are is about 6,000. In fact, all complex traits work that way.” So far, they’ve identified about 30 of the 6,000 genes that appear to play a role in pain.

Overlapping components of pain

But wait, it gets even more complex.

Dr. Ruth L. Chimenti, assistant professor of physical therapy and rehabilitation science at the University of Iowa, has been investigating novel ways of treating Achilles tendinopathy, a very common pain condition, particularly in runners.

Chimenti says her work has helped elucidate three overlapping components to pain – biological factors, movement factors, and psychological factors that are all intertwined together that contribute to someone’s overall pain experience.

First among these are the biological factors – think the triggering event like dropping something heavy on your foot or ramping up too quickly on your training plan.

Second, as a physical therapist, Chimenti is keenly interested in how continued movement and the stress it places on the painful area can either ease or exacerbate pain. “Exercise is both a risk factor for muscle injury, especially for athletes when they’re doing really high levels of exercise and putting load on their tissues. But it’s also a treatment,” such as how physical therapists help ease pain with exercises and incremental stress loading movements. Chimenti says that using movement to help the patient manage pain before reaching for a painkiller is preferable in most cases.

“Ultimately, what we want is to teach people how to manage their pain using non-pharmacological treatments,” says Chimenti. “That way, when you do get into a situation where you need to have a painkiller, you have it, but you’re not using that all the time.”

The third and final component of pain is the psychosocial response: how you perceive it and respond to it. “Particularly, I look at fear of movement, “says Chimenti. “For example, someone who’s been injured previously has a fear of having that injury occur again.”

With Achilles tendon pain, for example, many people who have the condition worry deeply about whether they’re going to rupture the tendon. “That can create a lot of fear of movement and can actually magnify the amount of pain you have,” says Chimenti.

Catastrophizing pain and the negative self-statements and thoughts about the future that often arise from it – simply thinking to yourself, my pain is terrible and it’s never going to get better, can cause as much damage as the underlying injury does. Building mental resilience in the face of pain can help, and again, understanding the triggering cause can help you gain more control over the pain and manage it with more confidence, less fear, and better outcomes. Knowledge is power, after all.

RELATED: The Injuries You Can’t See: How Mental State Impacts How an Injury Heals

More harm than good

Dr. Pooja Chopra, a physiatrist and chronic pain specialist with Hoag Orthopedic Institute in Southern California, says that from a fundamental, most basic definition, pain is an uncomfortable or unpleasant sensory stimuli that has an associated emotional response. That emotional aspect becomes even more important when dealing with chronic pain, which is defined as pain lasting longer than six months.

“Pain is a symptom,” says Chopra, “and it’s typically tied to a triggering event or conditions. Its main purpose is to act as a protective mechanism in order to teach us to avoid future noxious stimuli.”

But some athletes don’t listen, and wind up doing more harm than good by trying to dig deep and overcome certain kinds of pain. Chopra helps her patients learn when to stop by helping them recognize the different types of pain that can occur.

“If it’s a mild pain, such as muscle soreness after training or performing an athletic activity, that’s typically benign and can even be a sign of a successful training program.” says Chopra. “But it’s really critical that people, especially athletes, understand not to overdo it. That means not placing too much stress too rapidly, because that can cause damage to the underlying muscle tissues, bone, and even the ligaments.”

To avoid that, Chopra tells her patients to ramp up the intensity and duration of training sessions slowly and to see pain as our body’s way of communicating that something’s going on and that there’s potentially something wrong.

When you do reach that threshold where you might be doing more damage than good, Chopra recommends backing off: “The simplest treatment modality really is adequate rest. You want to remove the noxious stimulus and really allow the body to properly heat.” When it comes to pain, often, less is more, and stopping or slowing down is the best way to avoid a bigger problem later.

She also recommends icing sore parts to help reduce pain and inflammation (always use a barrier between ice and body, to prevent harming your skin). This is standard medical advice, along with the use of over-the-counter pain medications such as ibuprofen, that doctors have been giving for years. But lately, this received wisdom has come into question.

RELATED: Every Triathlete Needs To Understand Good Pain vs. Bad Pain

Pain relievers: When the cure becomes the poison

Though ibuprofen is often referred to as “Vitamin I” in endurance sports circles for its ubiquity and frequent overuse to manage the challenges of excessive exercise volume, a recent study Mogil and his team completed found that NSAIDs can actually increase the risk of developing chronic pain conditions.

The paper shows that individuals with inflammatory injuries who used anti-inflammatory medications – NSAIDs or steroid-based drugs such as cortisone – ended up with chronic pain more often than those who did not use these medications.

Mogil says it appears the inflammatory response the body generates after an insult or injury is part and parcel of repairing the damage. But if you tamp down that response with medications, you may be losing out on some of the natural healing benefit of the body’s complex inflammatory system.

“This means that steroids and NSAIDs are a very bad idea,” says Mogil. “While they’ll kill the pain in the short term, it could be to the detriment of long-term healing and the development of chronic pain.”

These findings need to be replicated before a blanket recommendation to avoid taking ibuprofen can be made, but “I feel very strongly that we are about to confirm that you shouldn’t use anti-inflammatories,” like ibuprofen or aspirin, says Mogil.

Acetaminophen, however, appears to be a safer choice. Exactly how it works isn’t understood, but because it doesn’t block inflammation, it doesn’t have that same drawback Mogil has observed with NSAIDs.

And before you pick up the ice pack, Mogil cautioned that long standing advice is also coming into question for the same reason: “Ice decreases inflammation, but you don’t want to decrease inflammation.” Instead, it appears that cytokines and other compounds in that inflammatory response improve your ability to heal.

Do endurance athletes have a higher pain threshold?

Whether athletes feel less pain or have a higher threshold for pain is still an open question, but there’s research out there to show that elite and high level athletes, particularly endurance athletes, have a higher pain tolerance. Becoming accustomed to being uncomfortable and making frequent visits to the so-called Pain Cave can help you build up a tolerance for it that folks who don’t push at those levels might have.

Mogil added that there’s so much variability in how each person responds to a pain stimulus that it’s nearly impossible to objectively quantify a unit of pain. Some athletes might be at the higher end of the spectrum in their tolerance of pain, but that doesn’t mean all athletes are.

“I think it depends very much on the sport,” says Mobil. “Some athletes need to fight their way through pain, either during training and or during competition. And the question is: Are they better able to do that because they have a lower pain sensitivity or is it that they’re just more motivated?”

And as far as Mogil is aware, no study has conclusively shown whether athletes are better at pain or just more willing to ignore it than other people. What’s more, “I bet competitive athletes would be under higher social pressure, to say the pain isn’t that bad just because of their self-conception. “

However, Chimenti says that despite that increased tolerance, pain is still an important piece of information. Learning – sometimes through trial and error – what’s normal for your body and being aware when an aberration arises is key to enduring without creating permanent damage.

RELATED: Triathletes Are Experts at the Pain Game

Pain is a message. Listen to it.

At its most basic, molecular level, pain is your body’s hard-wired instant messaging system that alerts your dumb brain that something is potentially wrong elsewhere in the kingdom. There are times when you need to honor that pain and stop the work, or risk doing real, permanent damage.

Steph McNamara, a former professional triathlete who now studies injury in endurance athletes, says she once “literally ran myself into having a stress fracture during a race and kept going,” which she admits was “a stupid thing.”

But knowing where to draw that line is a notoriously difficult challenge for most athletes who have long been advised to push through because “no pain, no gain,” and “pain is temporary, glory is forever.”

So, how much pain is too much?

It’s a simple question, but entirely individual because of the highly subjective nature of pain. Though pain does show up on brain scans, it’s virtually impossible to convey to another person exactly what you’re feeling. One person’s 10 on the pain scale is another person’s 2.

There is some evidence that you can expand your tolerance for pain through incremental loading; much the same way your muscles get stronger with repeated workouts, so too, it seems, can you nudge the needle of pain and increase your threshold to some extent.

“Desensitization therapy has been shown to be effective in certain rehab diagnoses,” says Chopra. Though there is something to the concept of just ignoring discomfort and pushing through, she also urges caution: “I’m fearful to say that you should push through pain to expand your tolerance for it. I’d rather be overcautious and get it evaluated first. That way, we know what we’re dealing with.”

Understanding your limit and knowing when to seek help for pain versus forging ahead is an important lesson that every athlete must learn for themselves. Chopra recommended checking with your doctor sooner rather than later so you can get an accurate diagnosis.

“Early diagnosis leads to early treatment, which really goes a long way because the last thing you want to do is irreversible damage.” She added, the last thing she ever wants to tell an athlete-patient is that they have to stop engaging in their preferred sport completely.

RELATED: Want To Increase Your Pain Tolerance?

Master the mind to manage pain

McNamara – who recently completed a PhD investigating how massage therapy works to repair traumatic injuries in skeletal muscle tissue and is currently in medical school – started her high-performance athletic life as a distance runner competing for Tufts University. But a severe injury in her sophomore year snuffed the high hopes for elite achievement that had developed.

After college, McNamara drifted into triathlon and raced briefly as a pro before the COVID-19 pandemic paused her promising multisport career. Across those athletic experiences, she’s learned that to compete in triathlon at a high level requires a relationship with and an understanding of discomfort, unpleasantness, and pain.

But not all pain is created equal, says McNamara: “The pain that I experience while running is very different from the pain I’ve experienced while biking. As a runner, I don’t put out as much torque as I do when I’m biking. So when biking up a hill, you’re really using your muscles a lot differently than you are when you’re running up the hill. It took me a lot longer to learn how to adapt to that lactic acid buildup from biking, even if I was in really good shape from running.”

She credits that different kind of pain to the idea that “I had never adapted to that high force output that you need on the bike to really turn the gears. My legs would burn immediately, and I think that kind of speaks to the difference between pain threshold versus pain tolerance.”

By pain tolerance (or pain endurance), McNamara means getting comfortable in that really uncomfortable low-level grind place that endurance athletes know so well. Over the years, she has expanded her pain endurance through regular exposure and learning how to alter her expectations.

For example, when running, if she encounters a hill, she knows that once she reaches the top, the burning in her legs will have a chance to ease off as the incline levels out. But on the bike, she now knows – and is prepared for the fact – that the grind will only continue once she reaches the top of that peak.

This adjustment of mental expectations is a big component of the pain puzzle, and top athletes in any sport have mastered their minds as much as their bodies to manage the pain when it inevitably comes calling.

“Talking about what causes pain is one thing. How you deal with it is completely another thing,” says McNamara. “Trying to get rid of the pain or minimize the pain by being more economical is one aspect, but just adapting to the fact that there’s going to be some pain no matter what is the other part of it. The psychology of it is like 95%,” says McNamara. In other words, pain is not just a physical phenomenon. Like most endurance athletes, she’s found that even when it hurts, she can still find another gear.

“It’s just a constant realization that you can push yourself that little bit further and nothing really bad is going to happen,” she says. Through triathlon, she has learned what she can tolerate, and that has applications for both sport and life in general. A dual PhD-MD student certainly knows something about the grind of academia, and enduring difficult things both in athletics and life and make us better, stronger people in all arenas. After all, what is a workout besides a loading session that applies stress, and yes, often some pain, to the body that forces it to grow in response so that it’s stronger, faster, and more prepared the next time?

Perhaps, then, pain is not always a stopping point, but a place for growth. “I’ve learned over the years that consistency is the number one thing that gets you to your goals as opposed to volume or intensity,” says McNamara. With that knowledge tucked deep into her muscles, she looks forward to resuming her professional tri career soon.