How Many Training Hours Does It (Really) Take to Conquer Ironman?

(Photo: Getty Images)

“If some is good, then more is better” has long been a popular adage in the endurance community. Those who have been involved in this sport for a long time will recognize a volume performance chart like the one below from Joe Friel’s Cyclist’s Training Bible:

Annual training hours by racing category

| Category | Hours Per Year |

| Pro | 800-1200 |

| 1-2 | 700-1000 |

| 3 | 500-700 |

| 4 | 350-500 |

| 5/Junior | 200-350 |

When I started in the sport of triathlon in the early 1990s, volume:performance charts like this were prevalent in every endurance sports training manual that you picked up. There was almost an unwritten, “Duh, of course better athletes train a lot more than beginners.” However, over the years, this fairly self-evident truth has been muddied (deliberately so) by some of those coaches, training books, and training platforms who realize the financial advantage to telling us what we want to hear: That it doesn’t matter if you only have a few hours a week to train, if you follow my proprietary top secret system, you too can become a champion! Of course, the truth—that higher levels of performance will require a greater time investment—doesn’t sell as well, but that doesn’t make it any less true!

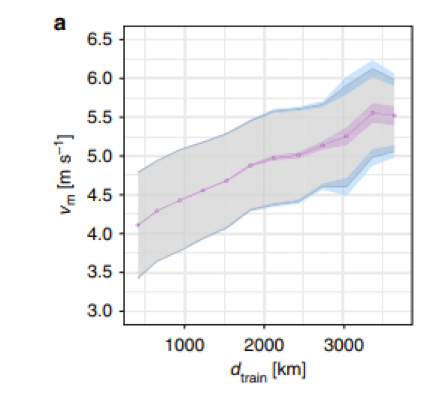

Going far beyond anecdote or coaching “rule of thumb,” this relationship between volume and performance has been validated in scientific research. Most recently, a 2020 study utilized “big data” analysis of some 14,000 runners (with 1.6 million training sessions!) to look at this relationship between volume and performance:

An obvious, near-linear relationship between total annual volume in distance and maximal aerobic pace can be seen, i.e. those runners who ran more miles were also faster. But, in triathlon terms, what does this relationship look like? How many hours of staring at a black line in the pool, turning the pedals over, and pounding the pavement is it going to take? It’s that question that not every athlete wants to ask: “Give it to me straight, coach. How many hours is it really going to take for me to reach my goal?”

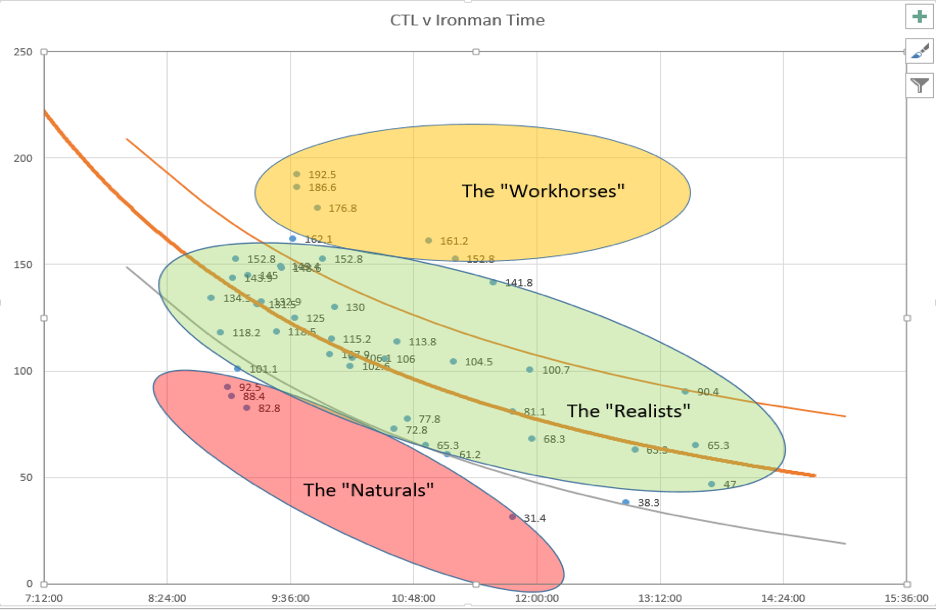

Over the 20+ years that I’ve been coaching triathletes, I’ve had the good fortune to work with all levels of athletes—from first-timers all the way up to world champions. And, while every athlete is certainly unique in their response to training volume, there are some observable patterns when it comes to the level of training volumes that we see among different performance categories. A few years back, I pulled multiple seasons worth of training load versus Ironman performance data from a number of athletes that I work with, with the following results:

The data shows the Ironman finish time, for a number of different athletes, plotted against their Chronic Training Load (CTL) at the time of their Ironman race. Following the trend line, the average 9-hour Ironman finisher was putting in a CTL of about 150 TSS/day (TSS being Training Stress Score, more on that here). The average 10-hour Ironman athlete was recording a TSS of 120 TSS/day, while the average training load for a mid-pack 12-hour athlete was 80 TSS/day.

While the distance that some of the points fell from the trend line clearly shows that there is individual variability in just how much training load it takes to achieve a given performance, there’s also a clear relationship that, for the average triathlete, more training load equals faster race times.

Let’s now take this a step further and ask the question: Just how many hours of training over the year prior to the race did it take to achieve a given level of performance?

The table below looks to answer that question by pulling the range of annual training hours for athletes in the middle of that performance category from the training load curve above.

Annual training hours, by performance category

| Category | CTL | Annual Volume |

| World Class Pro (sub-8 hours male; sub-9 hours female) | ~190 | 1,200-1,500 hours |

| Pro (8:30+ male; 9:30+ female) | ~165 | 1,000-1,300 hours |

| Kona Age Group Podium (sub-9 hours male; sub-10 hours female) | ~145 | 900-1,100 hours |

| Kona Age Group Qualifier (sub-9:30 hours male; sub-10:30 hours female) | ~130 | 700-1,000 hours |

| Mid-Pack Ironman (~12 hours) | ~80 | 500-700 hours |

| Finisher (17 hours + under) | ~50 | 350-500 hours |

The table shows a similar breakdown to Friel’s performance table for cyclists, but in triathlon terms. Specifically, Ironman triathlon terms. You can see quite similar numbers when comparing the recommendations given by Friel, with professional athletes typically recording north of 1,000 hours per year, and top amateurs ranging between 700 and 1,000 hours per year. Being low impact sports, triathlon and cycling are similarly ‘favored’ when it comes to absorbing some big training load.

RELATED: Triathlete’s Complete Guide on How to Train for an Ironman

Daily and weekly training load, by category

While it’s one thing to throw around annual training numbers, it’s quite another to dive in deeper and think about what this means to each level of athlete on an ongoing daily and weekly basis. So, let’s take a closer look at how these hours break down for each category of competitor.

World Class/Pro

While there are few ‘averages’ when it comes to world class Ironman athletes, 25-35 hour training weeks are commonplace. A typical week in the life of a world class pro will look like:

Swim: 20-30K (5-8 hours)

Bike: 250-435 (12-20 hours)

Run: 50-75 miles (6-8 hours)

Strength/Mobility: 2-3 hours

Training camp periods often exceed these levels, especially on the bike, and may amount to 40 hours per week or more, including 500 to 625 miles of cycling.

While the volumes above may be quite typical ranges for most long-course pro athletes, one of the key distinctions, in my experience, between the world class professional and the average professional is in the consistency of these big training weeks. Excessively frequent racing, interruptions due to injury or illness, or periods of burnout can have significant impact on the total annual hours and play a large role in determining which athletes are at the front of the race in the world championship events.

RELATED: By the Numbers: Who Makes A Good Pro Triathlete?

Kona Age Group Podium/Qualifier

There is definitely some overlap between the very top of the age groups and the professional field (as shown in the overlap in annual training hours). There are amateur athletes who, through opportunity, are willing and able to live “the pro lifestyle.” Training volumes for these athletes will be quite similar to training volumes for the pros—with a life of, essentially, going from one training camp to the next. In the younger age groups these athletes often have aspirations of racing professionally, and in the older age groups, they may be ex-elites from triathlon or a related sport where high volume training has just become “a part of life.”

While there are likely to be a few people racing at the front of the age group race on the Queen K with a very loose definition of ‘amateur,’ this is certainly not to say that all Kona qualifiers are living lives of leisure. Many have otherwise normal lives with busy, successful careers and family. The difference is that almost all of the time away from work and family is devoted to triathlon. Additionally, many will make use of training camps using a portion of their vacation time away from work to “live the pro life” for short segments during the year to boost annual volume. A typical mid-season (work) week in the life of a Kona qualifier often looks like this:

Monday: Off or Technique Swim + Core/Mobility (1.5 hours)

Tuesday: Moderate Hilly Bike (2 hours)/Easy Run (1 hour)

Wednesday: Easy Spin (2 hours)/Speed Run (1.5 hours)

Thursday: Off or Easy Spin (2 hours)

Friday: Speed Swim (1 hour)/Strength (1 hour)

Saturday: Long Swim (1.5 hours)/Long Bike (5 hours)

Sunday: Long Run (2.5 hours)

In total, this would be an approximately 20-hour training week, broken down as follows:

Swim: 3.5 hours

Bike: 10 hours

Run: 5 hours

Strength: 1.5 hours

RELATED: Triathlon Training Plan: Qualify for Kona

Mid Pack/Finisher

The average finishing time across all age groups, participants, and courses is around 12.5 hours. This will be the time on the clock when the bulk of athletes come in and, not coincidentally, it is also about the average total volume in a typical Ironman athlete’s week. Many athletes with busy jobs find themselves limited in the amount of time they can devote during the week to one session per day and so adopt the typical Weekend Warrior pattern that we often see with large proportions of the training week taking place on the weekend. A typical week in the life of the mid-pack athlete might look like:

Monday: Rest Day

Tuesday: Easy Swim + Core (1.5 hours)

Wednesday: Speed Bike + Run off (1.5 hours)

Thursday: Speed Swim + Strength (1.5 hours)

Friday: Easy Run with Drills (1 hour)

Saturday: Long Ride + Run off (5 hours)

Sunday: Long Run (2 hours)

In total, this would be broken down as:

Swim: 2 hours

Bike: 6 hours

Run: 3.5 hours

Strength: 1 hour

Athletes finishing the race closer to the 17-hour cut-off will often have a similar pattern during their periods of preparation (after all, the legitimate fear of the Ironman distance is going to encourage most to get a few long rides done!), but generally for shorter periods of time, putting in a good 12-16 weeks of preparation when their big event is looming, but adopting a “just exercise” mindset for the rest of the year leading to lower total volumes.

RELATED: Super Simple 20 Week Ironman Training Plan

Remember: Individual results may vary

While the above might sound quite formulaic, it’s worth casting an eye back to the chart at the start of this article to remember just how much individual variation there is in the performance:volume relationship. I’ve worked with athletes who have qualified for Kona on 10 hours per week. I’ve also worked with one athlete who didn’t qualify despite putting in an annual average of 20 hours per week. This variation persists all the way to the top of the curve. Some professional athletes do very well on 20-hour weeks. Others benefit the most from high volume consistent 30+ hour weeks. The point being here that while the above guidelines represent what most athletes might expect, your mileage may vary—quite literally.

Individual variation withstanding, hopefully the above guidelines will provide a good, realistic starting point on the time commitment that you can expect to make for different levels of performance goals. In my experience, a large deciding factor in whether an athlete is able to achieve their goals is in how much time they realistically have available within their life to train. Obviously there is a progression here; an athlete doesn’t merely decide to train 1500 hours this year and then become world champion. However, having this long term perspective and working towards creating space in your life to accommodate progressively bigger goals is a significant part of an athlete’s continued progress and long-term development within the sport.

RELATED: How Does a Triathlete ‘Go Pro’?

Alan Couzens is an exercise physiologist and endurance coach with a keen eye for data and a passion for analysis.