Gain Power And Efficiency To Become A Better Triathlete

Photo: Scott Draper

Get more powerful and efficient now to race faster the rest of the year.

This article was originally published in the March/April 2013 issue of Inside Triathlon magazine.

You’ve taken a year-end training break, are well into your off-season strength work and are now getting ready to jump-start your early-season base training. If you’re like most triathletes, that means building your endurance base with long, easy runs and rides, and maybe a relaxing pool swim or two each week to work on the flaws in your stroke. But this isn’t the time to go long or slow. Instead, follow the lead of two-time Ironman world champion Chris McCormack, who boosted his long-course speed on the lightning quick ITU circuit early last year, and you’ll be rewarded with a faster, more efficient and more economical body for the rest of the season.

Macca’s early-season focus on speed is a model that’s being embraced by more high-level triathlon coaches who have found that late winter to early spring is the best time of year to put speed into their athletes’ training schedules. They contend this “reverse periodization” cycle, in which triathletes begin the season focused on speed and then follow it with longer endurance sessions instead of the other way around, is particularly well-suited for long-course athletes and is the key to hitting your fastest Ironman ever. Here are the reasons why:

Better adaptation

During this last phase of the off-season, when training volumes are still low, your body is less stressed and better able to recover and adapt to high-intensity training. “Very few athletes give themselves enough of a break beyond the recovery period and into the adaptation phase, so essentially what happens is they load, recover, load, recover and they don’t adapt to the training or get the true benefits of what their training could be,” says Justin Trolle, an ITU coach in Colorado Springs, Colo., who also works with long-course athletes through his company Vanguard Endurance. But because cold temperatures in many parts of the country limit athletes from doing much volume at the beginning of the year, he says, introducing speed now “makes a lot more sense because you get a lot more recovery time between sessions and a better chance of getting greater adaptations.”

Increased efficiency

Doing speedwork improves your running, swimming and cycling mechanics because going faster requires you to pay more attention to good form. That not only makes you faster over short distances, but more efficient over longer distances—something to think about if you’re hoping for an Ironman PR later this season. “If you work on mechanical efficiency when the volumes are relatively low, then you’re not reinforcing bad habits,” says Trolle. “If you’re doing something for only a short period of time and you’re doing it perfectly every single time, then as you start to extend your training into the actual season, things will start to click and fall into place much better. So during the off-season, when the volumes are relatively low, is a great time to reinforce good habits and to make sure those things are in place when you start to increase the volume later on.”

Sport-specific strength

Weight lifting and plyometric work are great for building overall strength in the off-season, but speedwork trains the muscles and nervous system in a much more specific way to swim, bike and run faster. “Ultimately, if you want to become faster, you’ve got to train faster,” says Torsten Abel, a long-course pro and coach in Tucson, Ariz. “You can’t expect to break barriers with slow, long-distance training. Sprint training is like a strength workout. You’re recruiting a much larger pool of muscle fibers, and the more muscle fibers you keep awake and develop, the more powerful you become. You have to access these fibers to have a kick at the end of a race.”

Lower injury risk

Triathletes, especially older age groupers, often shy away from speedwork because they’re afraid of getting injured. But their injuries are often the result of not getting their bodies used to the demands of race paces early enough in the season, says Clermont, Fla.-based coach Tim Crowley, who coaches ITU pros and long-course age groupers through his company TC2 Coaching. When an athlete hasn’t done any fast running and says he’s now switching over into his pre-competitive phase and needs to go to the track, Crowley says it’s not surprising when he or she returns injured. “For masters athletes, or even anyone over the age of 30, speedwork is absolutely crucial,” he adds. “We need to keep all of the systems working, even at a small level, so they’re not dormant. If we’re not working them at all, we lose them.”

Keeping those fast-twitch fibers firing in short races as well as through speed-training sessions throughout the year is another key element in the yearly training plan these coaches employ to build a successful season for their Ironman, as well as ITU athletes. Crowley says it’s especially important for experienced age groupers, many of whom tend to train exclusively for iron-distance and half-iron-distance races, because “they want to travel, and if they’re going to travel, why travel to a short race? Training and racing shorter events is actually harder. It takes less time, but it definitely is a lot harder, because you have to do a lot more quality.”

Crowley has found from experience that the best preparation for Ironman is to have athletes do several Olympic-distance races. “For them, it’s quality speedwork that’s faster than race pace, but it doesn’t beat them up like a half-Ironman would,” says Crowley. “The best Ironman pro athletes come from short course, and we’re seeing those athletes now race into their early 40s. You look at Chris McCormack [who won the ITU Long Distance World Championships last year at 39] after he tried to make the [Australian] Olympic team. He’s said himself it made him a much faster athlete.”

Before jumping into any speed sessions, keep in mind that if you’ve taken any significant time off from training this winter, your body needs to be prepared for the intense workouts with at least four weeks of basic conditioning. Make sure you thoroughly warm up before and cool down after every speed-focused activity. And when beginning this phase of training, keep the speed sessions short to give your body time to recover and adapt. For best results, schedule your speedwork before any strength and endurance workouts of the day or training week so you’re physically fresh and mentally focused. Trolle, for example, divides his athletes’ weekly training schedules into two blocks—Tuesday through Thursday and Saturday through Sunday—and puts the speed sessions on Tuesday and Saturday, then follows them with strength and endurance workouts on Wednesday, Thursday and Sunday. “When you’re trying to do workouts that involve speed or mechanical efficiency, you want to do them while you’re fresh because they require a high heart rate, which we can’t get when we’re fatigued,” he says.

The kinds of speed workouts you do, the length of each session and the amount of recovery between each depend on many factors: your age, susceptibility to injury, years in the sport and finally whether you’re an athlete with a higher proportion of slow-twitch fibers and therefore might benefit from more speedwork, or if you’re more of a fast-twitch athlete who can regain fitness quickly with less speedwork. On the previous page are a variety of swim, bike and run workouts from Trolle and Crowley to choose from. Two sample weekly schedules on page 48 give additional guidance on how to balance the speed sessions with strength and endurance workouts in the early and the later part of this phase. As a general rule, your early-season speed phase should run about six weeks, followed by an additional four weeks of quality work before your first race of the season, says Trolle. With the additional taper and recovery weeks, that means you should start your early-season speedwork about 14 weeks prior to your first race of the season. Your weekly volume during this speed phase should be about half the number of hours as your peak training volume during the season, so if you’re an Ironman athlete who peaks at 24 hours a week, keep your total training time to no more than 12 hours a week.

Swim more frequently

ITU and long-course pros increase their pool time during the off-season to make major gains in their swimming. But avoid long swim workouts and distance sets unless you’re already technically proficient in the water. Think shorter and more frequent instead. “Having higher frequency helps your feel for the water,” says Trolle. “It’s easy in the off-season for people to lose their feel for the water. They’ll say ‘OK, I’ll swim just twice a week, but I’ll swim 5K each time I swim.’ You’re probably better off swimming three to four times a week and swimming half the distance.” Doing that not only allows you to get in quality swims, but keeps you mentally alert so you can work out the bugs in your stroke before putting in the fast stuff. “The most important thing is making sure you can swim well slowly,” advises Crowley, who advocates liberal use of swimming aids such as snorkels, fins, paddles and ankle bands during this period to focus on stroke mechanics. “The idea is to get them engaged, because people tend to swim mindlessly or, worse, they think too much.” He accomplishes this by using one-arm drills with fins and without fins, one-arm drills with paddles and without paddles, and swimming with a paddle on one hand and a fin on the opposite foot to drill the connection from the end of one arm to the opposite foot. Start with 8–10 x 25 with 30 seconds’ rest or a 25 easy free or backstroke in between, then build later in the speed phase to 3×500 swim as 25 sprint to 75 easy done five times continuously.

Crowley also makes his athletes swim twice a week with ankle bands during the winter to improve their body position, stroke rate and the force they apply to the water with each stroke. “If you’ve got an ankle band and you’re really lengthening out your stroke, but you’re not developing enough force, you’re going to sink,” he says. “If you’ve got good turnover and good cadence but your body position isn’t optimal, you’re going to sink. All things have to happen correctly in order for you to cross the pool.” He starts his ankle-band workouts with 8×25 on a 30–45-second send-off and progresses by the end of the speed phase to 500 total yards (or meters) as 20×50 or 10×100. Once you’ve dialed in your stroke, add in some short, fast intervals to your workouts, making sure you take plenty of rest and maintain good form as you increase your turnover. Mix it up with 20×25 with 15 seconds’ rest between each interval one day, 10×50 with 30 seconds’ rest another day and 5×100 with a minute’s rest a third day. As you get fitter, reduce the rest intervals and do one fast and two easy one week; one fast, one easy the next week; and two fast, one easy the following week. As the weeks progress, you should have a faster and more coordinated turnover on the fast sets and feel yourself glide through the water with less effort on the easy sets.

Focus on power and cadence

Take advantage of the indoor trainer this winter to raise all of your key power numbers, particularly your max power, one-minute and five-minute average power output. “Your one-minute power is directly related to your five-minute power, which is directly related to your 20-minute power and to your 40K and Ironman power,” says Crowley. “You’re still going to need to do the endurance work, but the idea is that you raise those parameters during the wintertime first. Then as the weather gets nicer, we increase our volume and specificity. So we go from 20-minute intervals indoors to maybe hour-long intervals outside. It makes so much more sense because why would we want to do our intensity work while we’re training for a long-course race?”

Winter is also a good time to develop raw bike strength. Trolle accomplishes that with workouts like 5×10 minutes in a big gear at 50–60 RPM with five minutes of easy spinning between on a steep hill or the trainer. He also improves his athletes’ mechanical efficiency by regularly forcing them to spin at 20–30 RPM faster than their natural cadences. Cadence has a direct impact on power output since wattage is a product of the force you apply to the pedals per revolution and your RPM. “As time goes by, your natural cadence will go up” by about 4–5 RPM per year, Trolle says. “As a person becomes more mechanically efficient, his ability to produce wattages at higher cadences is improved.” That means more cycling power per unit of body weight, which will permit you to become a leaner and faster runner, particularly in hot and humid races like Ironman Hawaii, without having to give up your cycling gains.

If you can ride safely outside during this time of the year, do it, but avoid rides longer than three hours. “You don’t need to be clocking in five- to six-hour rides,” says Trolle. “There’s going to be plenty of time to do those in the season itself.” Instead, inject some quality into your longer rides with 6×10-minute or 8×10-minute efforts at 110 percent of Ironman or 70.3 race pace, he says. Also avoid doing all of your cycling workouts on the trainer, especially in the latter stage of this phase as you prepare for your early-season races. “When you put a person on a trainer, they hold a very consistent wattage, within a 10-watt range,” Trolle says. “But if you look at an athlete’s power files from a race, it might vary by a 15- or 25-watt range. When you wind up training all the time on a trainer and then you have to deal with the fluctuations in a race, the amount of fatigue on the muscle is much higher. We see that a lot in athletes who come from Chicago and Indianapolis.”

Run better to run faster

Sprinting on a track isn’t the only way to get fast. Take time this winter to improve your running mechanics and you’ll be faster by year’s end. The 2012 winner of the Ironman World Championship, Pete Jacobs, went from being a three-hour-plus marathoner off the bike to a 2:41 runner in the heat and humidity of Kona largely by concentrating on his running form—proof that major gains can come from an area most athletes neglect. Watch good runners and compare their form to your own race photos. Better yet, put a camera on a tripod and videotape yourself running from the front and side. The way you hit the ground—forefoot, mid-foot or heel—depends (to a large extent) on your biomechanics, but the key elements of an efficient stride are an erect posture leaning slightly forward from the hips, feet striking the ground under the body’s center of gravity, little vertical movement of the head and a pronounced rearward leg extension. Boulder, Colo.-based triathlon running expert Bobby McGee compares efficient running to a controlled forward fall. There are several ways you can train yourself to adopt that ideal running position without feeling like you’re actually falling on your face.

Tire pulls and hill repeats like 6×1000 meters up a moderate hill are great ways not only to improve running form, but to also build the necessary leg strength for a more forceful push-off. Box jumps, split lunges, jumping lunges and other kinds of plyometric exercises are also valuable to improve your ability to “pop” off the ground more quickly with every stride. “Most of the energy used in running is not produced muscularly,” says Trolle. “It’s produced from elastic recoil and tension, like a spring that bounces off into the next stride.”

For both track work and hill repeats, start with shorter intervals, like 6×200 meters with a minute rest, focusing on good technique, then build the intensity and gradually extend the distance of the intervals (and the rest period between each) to 6×400, 6×800 and 6×1000 as you are better able to maintain good technique for longer distances. “We want to be able to carry that technique through,” says Trolle. For athletes in cold-weather climates, Crowley prescribes an endurance run outside, followed by 30-second strides on the treadmill to develop leg speed. He starts with 10 intervals with 30 seconds’ rest and progresses up to 20 minutes of 30 seconds on, 30 seconds off intervals on the treadmill at their 100-meter stride outdoor speed (five minutes per mile equals 12 mph) by having them jump off, grab the handles and straddle the belt, rest and jump on the moving belt again. By cranking up the incline, they can also do hill repeats on the treadmill, with a 20 seconds on, 40 seconds off interval to allow them to fully recover.

Speed up transitions

Don’t wait until the race season to begin your brick workouts. Do them once a week now, and you’ll be faster in transitions when your season starts. “So much of going from swim to bike and bike to run is about changing blood flow and where it goes to the muscles,” says Trolle. “The quicker you can do that, the quicker you can get up to being efficient again. If you can get up to speed within 30 seconds instead of three minutes, then it makes a big difference in your overall time.” If you live in a cold-weather climate, see if you can bring your bike and trainer to the pool or an indoor track for indoor brick sessions. “Most pools will let you, and it’s amazing how much you get into deep and meaningful conversations when you do transitions on the pool deck,” Trolle says.

Crowley especially likes winter bricks for the variety during the cold and dreary months. “I’ll have athletes who have a treadmill and a bike trainer do a bike-run, but not as a hard effort,” he says, such as 4×15 minutes on the trainer with a five- or 10-minute easy run on the treadmill. “It also gives their butt a break from sitting on the saddle.” Trolle schedules one swim-to-bike transition and one bike-to-run transition a week for his athletes during the first half of their speed phase. During the second half, he has them do “stacked bricks,” consisting of swim-bike-swim-bike-swim-bike or bike-run-bike-run-bike-run sessions as a single workout. “When I put those workouts on the programs for my athletes, they’re horrified initially,” he says, “but eventually they start to love them because it creates a lot of speed and they feel like they’re racing again.” And isn’t that what we all need to make it through the long, cold winter?

###

RELATED: Strength Building Exercises

The simplest way to teach your body to run with good form is to find a moderately sloped hill with a flat section at the top. Running up the hill with good leg extension will force your body to lean forward from the hips, increase your stride rate (another element of good running form) and help keep your foot plant under your center of gravity. As you reach the crest of the hill and run on the flat road, concentrate on maintaining the same forward lean, leg extension, foot plant and stride rate. Do multiple hill repeats to get the hang of it once a week, running 500 meters uphill followed by another 500 along the flat crest of the hill.

Box jumps, jumping lunges and other kinds of plyometric exercises can improve your ability to “pop” off the ground more quickly with every stride. The idea is to get your leg muscles conditioned for “elastic recoil and tension,” says Trolle, so they can be used “like a spring that bounces off into the next stride.” The best place for box jumps are soft surfaces, such as the padded boxes and floors found in many gyms, to minimize the landing forces on your leg, but you can also do a series of ascending jumps on stadium steps (as shown). Begin with 10 minutes of running to make sure your muscles are fully warmed up for the explosive contractions that will be required for this exercise. Then start with your hands at your sides, feet roughly shoulder-width apart and swing your arms as you jump up to the next step, taking 2-3 seconds’ rest between each jump. Do 8-10 jumps, then walk back down and repeat the set three times.

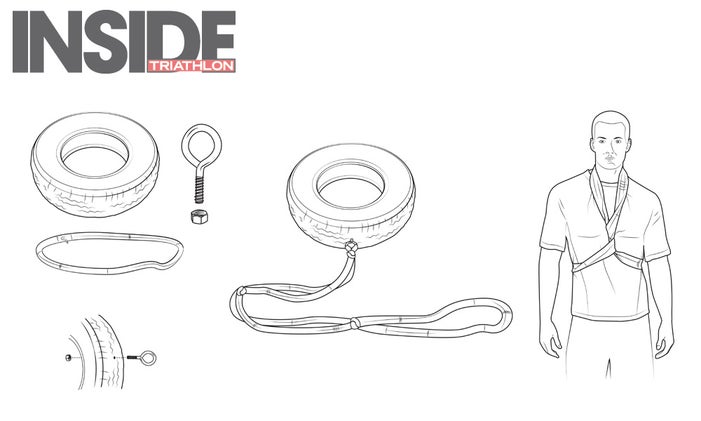

If you live in an area without hills or you just want to add variety to your hill running routine, try a drag sled. Dragging a tire sled on grass, dirt or even an asphalt road is a great alternative to improve running form (avoid dragging the tire on tracks to prevent wear and tear of the track surface). You can easily build your own drag sled by drilling a hole into a used car tire, fastening an eye bolt to it, then attaching a series of three used bike tubes tied to one another. For comfort, use a mountain bike tube to go around your neck and chest (twist it around your chest as shown on the opposite page). Trolle has his athletes do 6–8 x 100-meter sprints pulling the tire before early-season track workouts to reinforce good form. As they become stronger, he’ll add tire work after their hill repeats to improve leg strength.

Speed to Burn

Incorporate these speed sessions into your early-season workouts to build speed and efficiency.

Swim:

> 20×25 fast with 15 seconds rest between intervals

> 10×50 fast with 30 seconds rest

> 5×100 fast with 60 seconds rest

> 8×25 or 10×50 with good form with 30 seconds rest using ankle straps

> 10×25 fast with 30 seconds rest using paddle in one hand and fin on opposite foot

Bike:

> 5×10 minutes in big gear at 50–60 RPM on hill or trainer with five minutes easy spinning between

> 6×10-minute or 8×10-minute efforts at 110 percent Ironman race pace in long ride

> 4×15-minute efforts at 110 percent 70.3 race pace on the trainer followed by a 5–10-minute easy run between on treadmill between efforts

> Warm up and cool down with 10 minutes of spinning at 110 RPM in above workouts

Run:

> One-hour endurance run followed by 10×30 seconds at 100-meter stride speed with 30 seconds rest on treadmill (set at 10 mph for 6-minute miles, 12 mph for 5-minute miles)

> 6×100-meter tire pulls

> 6×200 hill repeats with good form, run easy downhill after each repeat

> 6×400 fast on track, 200 easy jog between

> 6×1000 repeats with good form, first 500 uphill, second 500 on flat; jog to start after each repeat

RELATED: Transitioning From Single-Sport Athlete To Triathlete

How to Build Your Own Drag Sled

Start with a used passenger car tire (you should be able to pick one up at your local garage or tire shop at no cost), three used bicycle tubes (make sure one of them is a mountain bike tube) and a 4- to 6-inch-long eye bolt and nut. The eye needs to be big enough so that you can loop an inner tube through it. You’ll also need a power drill and a drill bit big enough to create a hole for the eye bolt.

Drill a hole through the center of the tire (preferably in the groove), then insert the eye bolt and fasten the nut to the end of the bolt so that the eye extends about 3 inches from the surface of the tire.

Cut off the valves from the bicycle inner tubes. Loop the first inner tube around the eye bolt, then tie another tube to this tube. The last tube, which should be a mountain bike tube, can then be tied to the second tube.

Extend the bicycle tubes on the ground in a straight line away from the tire. Then open the loop of the last (mountain bike) tube and step into the center. Pull the tube up to waist level, twist the tube twice, then pull it over your head and let the tube rest on the back of your neck as shown. Take out any kinks in this last tube so its surface is completely flat on your chest and waist, and you’re ready to drag your new tire sled.

Jumpstart

Below are examples of how an athlete who peaks at 25 hours of training a week during the season might schedule speed workouts during the early and late phase of this speed focus.

Early Speed Phase

Monday

45-min recovery/technique swim incorporating 8×25 fast with 30 sec rest using ankle straps. 45-min strength/core work.

Tuesday

1-hour run incorporating 6×100 tire pull, followed by 6×400 at 10K pace on track; 200 easy jog between. 1-hour technique swim with 10×25 easy with 30 sec rest using paddle in one hand and fin on opposite foot; switch after five.

Wednesday

1.5-hour bike; warm up and cool down with 10 minutes of spinning at 110 RPM, then 5×10 minutes in a big gear at 50–60 RPM on a hill or trainer with five minutes easy between.

Thursday

1-hour run with 6×200 hill repeats followed by 30-min fartlek on trails. 1-hour easy recovery ride.

Friday

45-min technique swim with 10×25 fast with 15 sec rest between intervals. 45-minute strength/core workout.

Saturday

2-hour ride/run with 6×8-min efforts at 110 percent Ironman race pace, followed by 15-min transition run.

Sunday

1-hour swim-bike brick as 45-min swim incorporating 8×25 with 30 sec rest using ankle straps followed by 15-min bike.

Total: 11.5 hours

Late Speed Phase

Monday

45-min recovery/technique swim incorporating 10×50 fast with 30 sec rest using ankle straps and one-arm drills with paddles and fins. 45-min strength/core work.

Tuesday

1-hour strength-endurance run incorporating 6×1000 hill repeats, followed by 6×100 tire pull. 1-hour technique/sprint swim with 3×500 using paddle in one hand and fin on opposite foot swum as 25 sprint and 75 easy five times continuously.

Wednesday

1.5-hour bike; warm up and cool down with 10 minutes of spinning at 110 RPM, then 5×10 min in big gear at 50–60 RPM on hill or trainer with five minutes easy between.

Thursday

1.5-hour alternate bike-run brick, broken as 3x(10-min bike at Ironman race pace followed by five-minute moderate run, then five-minute easy jog on treadmill or track) with 30 min easy running for warm-up and cool-down.

Friday

45-min technique swim with 10×50 fast and 30 sec rest between intervals; plus 10×25 with paddle in one hand and swim fin on opposite foot. 45-min strength/core workout.

Saturday

3-hour ride/run incorporating 10×8-min efforts at 110 percent Ironman race pace, followed by 30-min transition run.

Sunday

1-hour alternating swim-bike brick as 3x(500 swim, followed by 10-min bike at Ironman race pace).

Total: 12 hours

RELATED: The Mental Game Of Triathlon

“Like” us on Facebook to get the first look at our photo shoots, take part in lively debates and connect with your fellow triathletes.