Can a Personality Test Give Your Performance a Boost?

(Photo: Brad Kaminski/Triathlete)

To compete in triathlon, an athlete needs a certain level of drive. After all, not everyone can spend the kind of time and effort required to master not one, but three sports.

But while it’s easy to joke about triathletes tending to be “Type A,” the fact is triathletes of all stripes are motivated in lots of different ways. They approach their training differently, their race day mentalities are varied, and the type of feedback they require in order to improve? You guessed it – that’s all over the place, too.

Therefore, it makes sense for coaches, training buddies, and athletes themselves to gain as much insight into what makes them tick as possible. Parker Spencer, Head Coach at Project Podium, USA Triathlon’s men’s elite development program, certainly thinks so. In fact, he says that they use the CliftonStrengths Assessment (a popular online personality and talent assessment designed to identify what individuals naturally do best) for everything—who they pair up as roommates, who travels together, how Spencer communicates about workouts and training plans, and, notably, how he gives each athlete feedback.

“In the iPhone notes on my cell phone, I have a note for every single athlete with their CliftonStrengths profile and how to give them feedback after workouts and after a race,” he says. He refers to it religiously—for good reason. One of his personal top five themes (which is how CliftonStrengths identifies and describes people’s natural strengths and tendencies) is positivity. “If I see an athlete who’s underperforming in a race, my instinct is to tell them something positive when they finish, so it lessens the blow a bit,” he says.

But that’s not how every athlete thinks, which Spencer learned after using that approach on one of his athletes.

“I said something positive after he didn’t have a great race,” Spencer says, “and then he didn’t talk to me for three days because he felt like I didn’t care about his performance enough.” Eventually, they talked through the miscommunication, and now, Spencer refers to his notes before offering feedback to ensure he’s giving that athlete—and the rest of the athletes on the Project Podium team—the feedback he needs to continue improving.

“It’s revolutionized the way I coach,” Spencer says. “Years into this, I have the best coach/athlete relationships I’ve ever had.” And, because each athlete on the team knows his own strengths, as well as his teammates’, they also have the best team culture they’ve ever had—not because of any magic, but because they have the tools and language to communicate effectively with each other, even if their personalities and approaches differ significantly.

RELATED: Dear Coach: How Do I Develop A Strong Coach/Athlete Relationship?

What personality tests can (and can’t) tell us

Still, it’s also important to understand the limitations of assessments like CliftonStrengths, Enneagram, Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), DISC, and the countless others available, either free or for a fee. These assessments are frequently used in business settings (especially during the hiring process) and for team-building purposes (both in business and beyond) but may also be used in therapy to aid in diagnosis, by individuals seeking better insight into their own motivations, and even for entertainment purposes (along the lines of how many people use horoscopes). Each assessment has a slightly different approach and its own specific results; in some cases, that may make a particular assessment best-suited for a certain use, but they all offer insights into general personality, motivation, and natural tendencies.

Elizabeth L. Shoenfelt, Ph.D, President-Elect of the Association for Applied Sport Psychology (AASP) and a University Distinguished Professor, Emeritus at Western Kentucky University, has used DISC for team building with sports teams, business teams, and university-based groups since the mid-1980s. She prefers DISC to other popular tests due to its simplicity—which is particularly important in situations where she’s only working with a group for a short period of time.

“Typically, after a training/team building session, everyone understands all four dimensions, their own profile, and most people can estimate pretty accurately the DISC styles of others they know pretty well,” she says. “When I have talked to people who have completed MBTI or other more complex profile systems, they may remember all or part of their own profile, but certainly cannot articulate other profiles.”

But even if a person fully understands and retains the information from any of these assessments, there remains more to the story, Shoenfelt says, because “behavior is multiply determined and much more beyond DISC (or another test profile) determines how a person responds in a given situation.” For example, when people are under pressure or are totally at ease with no reason to adapt, their natural style is more likely to surface. In other circumstances, they might act differently because of how they’d like to be perceived, even if that’s not what comes naturally.

Additionally, she says, these tests are “reflective” instruments. “The test taker answers questions about themselves, the scoring key consolidates these into a profile of results indicating styles or types. The results are perceived as amazingly accurate – ‘This really is what I am like!’” she says. “Of course, it is what you think you are like – you just told the test what you are like.”

Shoenfelt also points out that, while the characteristics of a good test are reliability/consistency and validity/accuracy, it’s entirely possible for a test to be valid for one purpose but not another. She uses a bathroom scale, for example; if it gives you an accurate weight three times in a row, it’s a reliable measure of bodyweight. But no matter how accurate it is for that purpose, it does not provide an accurate measure of anything else—height, intelligence, prowess in the kitchen.

RELATED: Our Guide To Triathlon Coaching Styles

All about the environment

If you remember nothing else about this article, here’s the important takeaway: No specific personality or type is inherently better than others. Not in life, and not in sport.

In fact, that’s one of the things Spencer finds most interesting about CliftonStrengths. Gallup initially put this assessment together, he says, because they wanted to see why high performers were so high-performing.

“They did all this research with over 20,000 high-performing individuals,” he says, “and what all that came back with is that none of them had anything in common.” In other words, it wasn’t their personality or profile that made these folks successful—it was the fact that all of them worked and performed in environments that let them make excellent use of their strengths that made the difference.

That tracks with Shoenfelt’s experience regarding the concept of equifinality. “That is, a diversity of pathways may lead to the same outcome,” she says. “[T]here are different ways to accomplish success. Individuals with different styles can all be successful.”

What that means in an environment like Project Podium is that Spencer takes note when an athlete is, for example, highly analytical, and he makes sure that athlete has access to the data they need and the ability to analyze it with a coach. On the other hand, if an athlete is extremely adaptable and doesn’t care as much about delving into the data, he knows they trust him to simply tell them how to work out the way they need to … and that they might struggle to share as much detail in TrainingPeaks as their analytical teammates.

It’s also wise to remember that any strength can become a weakness if not managed the right way. Being analytical is a great way to gain important insights into your training and performance, but if you focus solely on that without listening to your body’s cues, you could push through when you need to recover and cause serious injury. And while an adaptable athlete has an edge in that they can roll with changes without getting flustered, they also run a higher risk of going with the flow, even when it’s to their detriment. If they start hanging out with less committed athletes, for instance, that attitude could easily influence their own attitude.

RELATED: The Psychology of Setting Motivating and Satisfying Goals

Testing takeaways

Whether you’re an athlete taking the test or a coach, like Spencer, using an athlete’s results to better help them, there are a few things to keep in mind about what these tests can and can’t do. From CliftonStrengths and DISC to MBTI and Enneagram, keep the following in mind as you study the results:

- Many factors influence behavior. “Interpersonal styles can be an aid, but they are not a comprehensive answer to understanding an athlete,” Shoenfelt says. “Different athletes will be motivated by things in their life other than their interpersonal style—family responsibilities/obligations, finances, religion, work or school obligations, immediate and long-term career or life goals, medical issues, etc. Current status, as well as long-term goals in each of these realms, can have a big influence on an individual.”

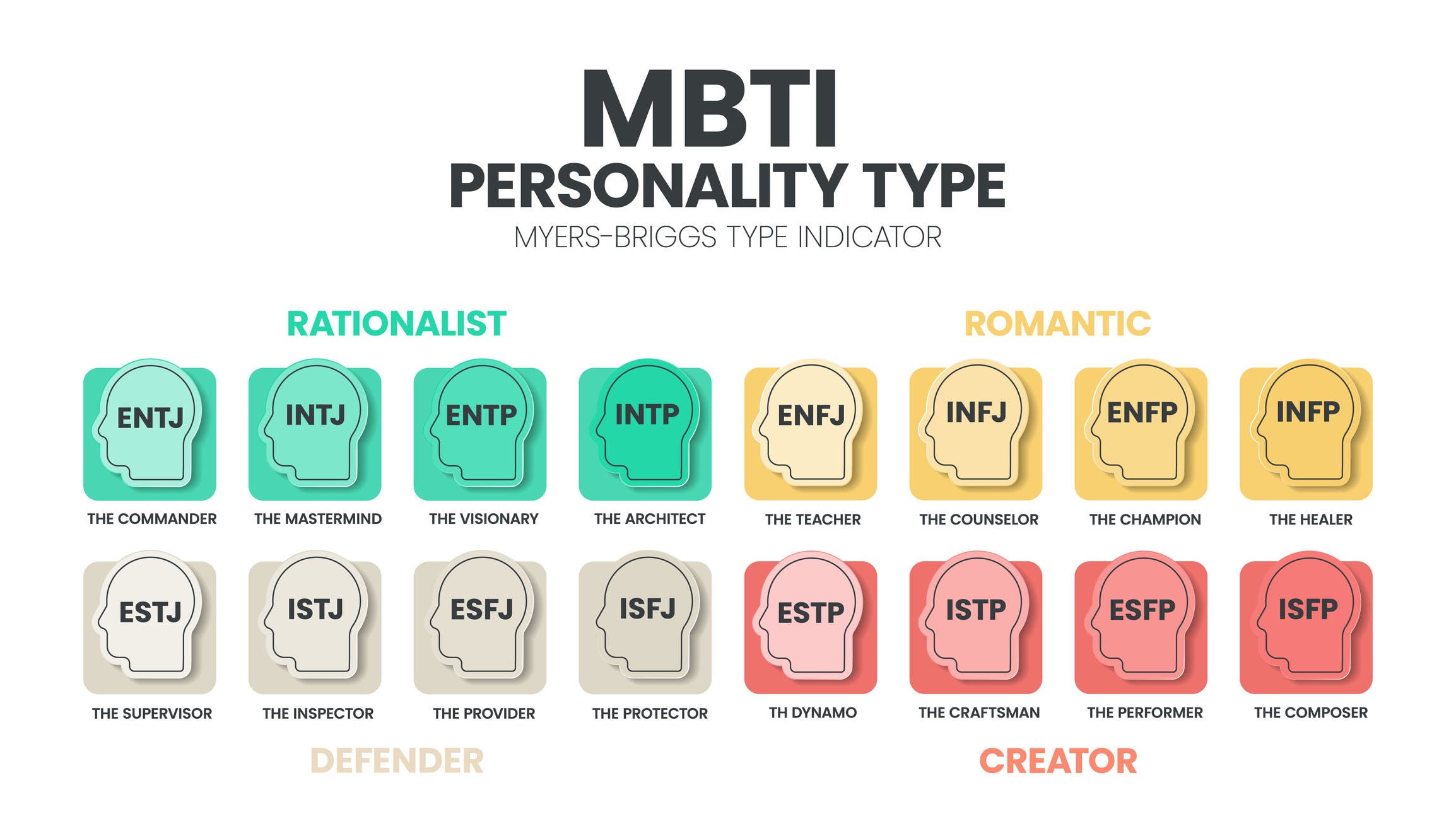

- A test result isn’t an excuse for bad behavior. Take, for example, the final letter in the MBTI: J vs. P. Someone with a J in their profile is generally more structured, considering decisions to be final, whereas someone with a P is typically more flexible, easily adapting to changes or even preferring plans to be more open-ended. Being a P doesn’t mean it’s okay to ignore a deadline, just as being a J doesn’t mean it’s okay to lose your mind when a plan needs to change. However, that information can help someone understand what they might need to work on or ask for help with—and it can help a coach know how to communicate timelines and potential curveballs with their athletes.

- You won’t become an expert on this overnight. “We’re talking about psychology here. It’s as complicated as life gets,” Spencer says. There are loads of resources available to help coaches and athletes better understand the mental aspect of the sport, and while these personality assessments are a tool in that toolbox, they’re not the only way to gain greater insights into how to motivate an athlete.

- There’s no single test that will give you all the answers. Whether you’re looking at DISC, CliftonStrengths, MBTI, Enneagram, or others, the fact is that each test is going to be accurate in its own way, and the further you delve into each one to really understand what the results mean, the more useful it will be. “Although the tests or samples of them are available online, to use the results, one needs to understand the dimensions of the particular test and how they translate into behavioral tendencies,” Shoenfelt says. “It is not rocket science, but it does require some training or self-instruction.” These tests are designed to provide self-awareness, but it’s specific to a given situation “The tests can help individuals identify their natural strengths to capitalize on and tendencies they may need to pull up in a given situation to be more effective,” she says—and that will help them know how to adapt their behavior to meet the demands of a particular situation, like grueling practices or stressful travel leading up to a race.

RELATED: Enneagram for Triathletes: What Motivates You in Swim, Bike, and Run?

A primer on personality tests

| Clifton Strengths | Used in various ways, from business and career development to navigating personal relationships. Looks at 34 themes (like responsibility, positivity, achiever, competition) through the lens of four domains of leadership to identify natural strengths and talents. |

| DISC | Used to improve work productivity, teamwork, leadership, sales, and communication, according to the assessment’s own description. Breaks down personality using four categories (Dominance, Influence, Steadiness, and Compliance), which are determined by how test-takers identify with 28 statements. |

| Meyers-Briggs Type Indicator (MTBI) | Used by companies during the hiring process, also big in pop culture. Uses 93 questions to sort applicants by four key groupings (extraversion/introversion, judging/perceiving, intuition/sensing, and thinking/feeling), which places test takers into one of 16 personality types. |

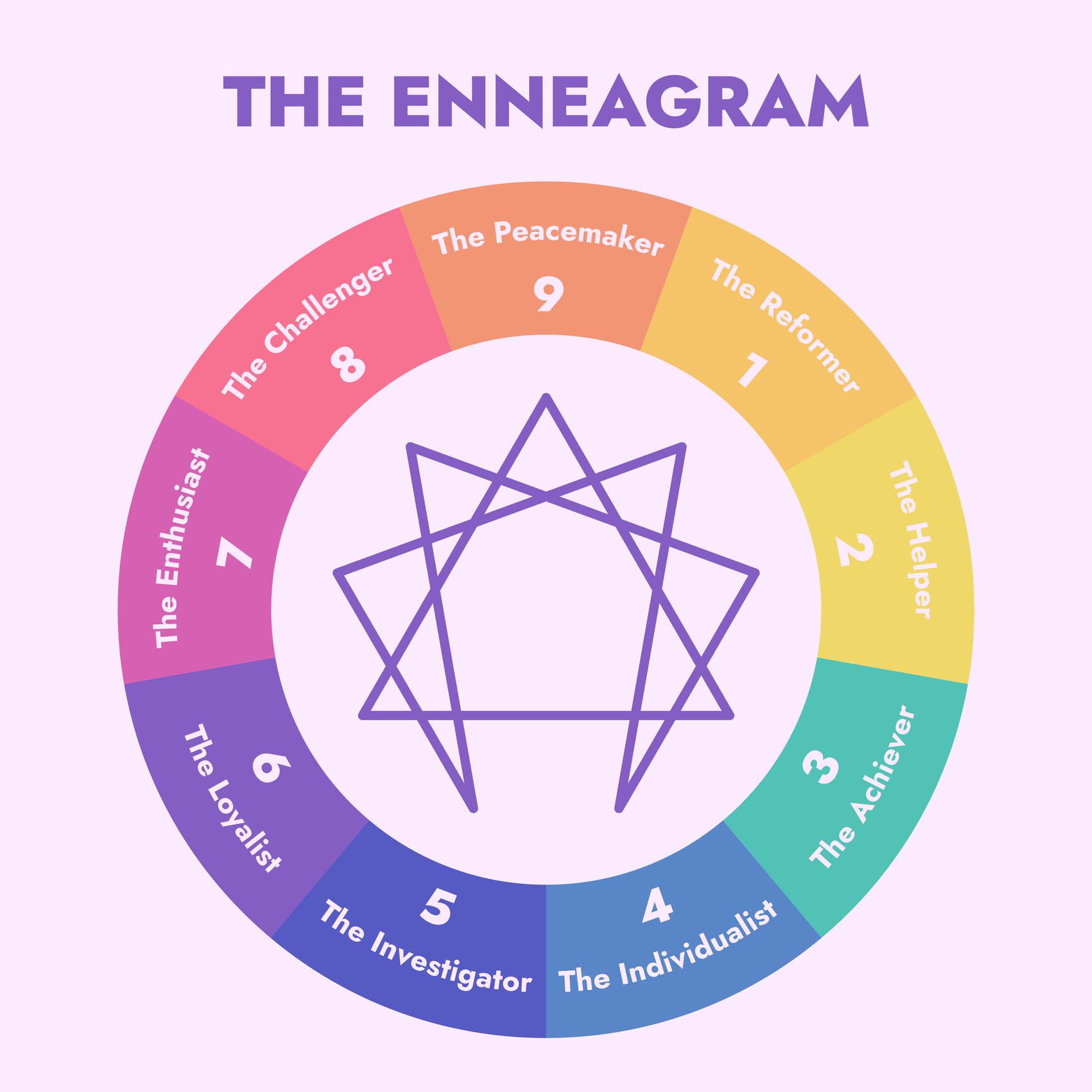

| Enneagram | Designed to provide a more objective look at oneself and others, it’s frequently used for everything from personal self-discovery to parenting to business settings, and is another one that’s quite popular on social media. The 144-question Riso-Hudson Enneagram Type Indicator (RHETI) identifies which of the nine basic personality types the test-taker is closest to, from Type One (The Reformer) to Type Nine (The Peacemaker). |