The Science Behind Low-Carb High-Fat Diets for Tri

At the end of the 2016 Ironman World Championship, Swiss professional Jan Van Berkel knew he needed a change. Just a couple of weeks before the big race, he had crashed on his bike, and on race day, he wasn’t fully recovered. He had to drop out.

But Van Berkel felt there was also something in his fuelling and nutritional structure that wasn’t working. And that’s why he got in touch with coach and exercise physiologist Dan Plews, who was known for using a Low-Carb High-Fat (LCHF) approach for long-distance triathlons. Two years later, Plews himself would go on to set the Kona age-group record with a time of 8:24.36.

RELATED: Triathlete’s Complete Guide to Fueling and Nutrition

“I was not happy with my results in general, and I knew how important nutrition is for performance,” said Van Berkel. “I was open to an LCHF approach, and that is why I contacted Dan.” It didn’t take long before the two were not only discussing nutrition, but also setting up a professional coach-athlete relationship that would prove to be very successful in the coming years.

But conventional endurance training says we require huge amounts of energy, so how could a LCHF diet possibly work for events that span hours? And what precisely is LCHF?

The Science: Why Low-Carb High-Fat Works

First, an LCHF approach is not a ketogenic diet. “[A ketogenic diet] is generally defined as [consuming] less than 50 grams of carbohydrate per day. In contrast, an LCHF is defined as around 130 grams per day,” Plews said. “But I don’t like to say it’s only 130 grams. There’s actually a sweet spot, and some people need a bit more, and some a bit less (for example, those with insulin resistance and glucose intolerance).”

Then there’s the connection to long-distance triathlons, which are never performed at maximum intensities for long. In this scenario, using fats instead of carbs as a fuel source may be beneficial and save athletes from the dreaded bonk at the end of the marathon (if not earlier in the race).

“One of the prerequisites for long-distance triathlons is the conservation of endogenous (internal) carbohydrate stores,” Plews said.

If someone is working at 300W, for example, and that comes 100% from carbohydrates, it's only a matter of time before the endogenous supply will run out and bonk.

The benefit of switching to fats instead of carbs, at least from a theoretical point of view, is that fat is a potentially unlimited energy source for the body. Even a super lean individual (say, 8% body fat and weighing 155 pounds) can store up to 25,200 kcal of fat—versus 1,500 kcal carbs stored in the muscles and liver with a specific carb load.

But even Plews, who has developed a specific way to approach LCHF, says he’s not anti carb and makes an essential point about the requirements of long-distance triathlons compared to other endurance events.

“An LCHF approach, from a performance perspective, is only likely very beneficial for a sport that is dependent on having high levels of fat oxidation, and the depletion of endogenous carbohydrate stores is a natural factor,” he said.

In a 10k running race, a half marathon, and even in a marathon, you're very unlikely to run out of endogenous carbohydrate stores. But as soon as you get over four hours, that's starting to become a problem. And over 7-8 hours, it becomes a major problem.

He says that along with VO2max, running economy, and other performance factors, FatMax (maximum fat combustion rate) is something athletes need to consider when training long-distance triathlons. The reason is that Ironman races take place at around the aerobic threshold (the easy effort that you can sustain for hours) and that the FatMax—for most people—occurs at Ironman intensity of around 75% of maximum heart rate.

Science: Why LCHF Might Not Work

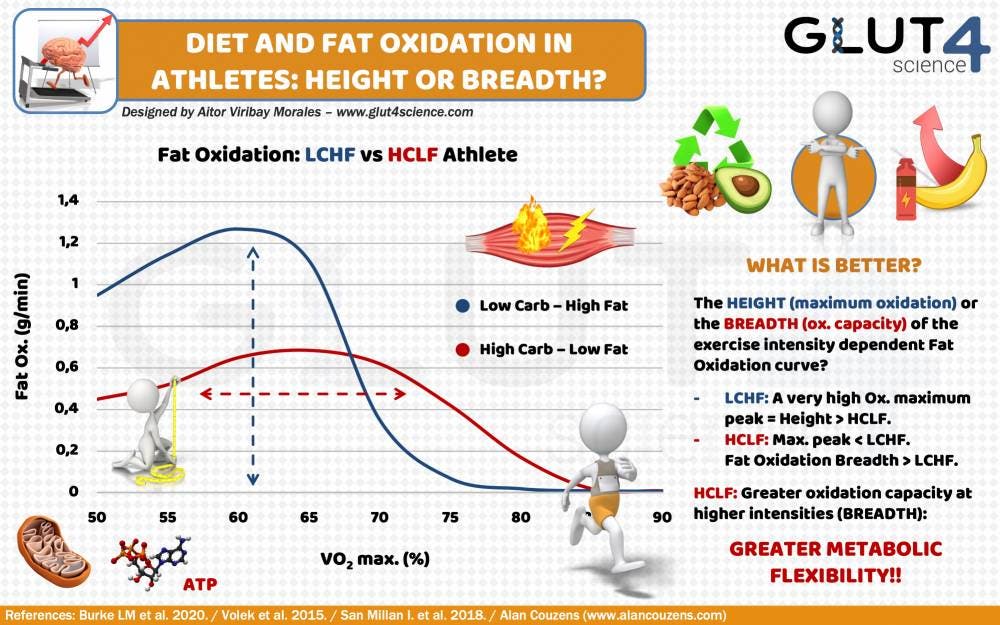

Although you may increase your FatMax by following an LCHF approach, other nutritionists and researchers stress an important difference between a “high FatMax” (here, height meaning maximum oxidation) and a “wide FatMax” (here, breadth meaning oxidation capacity). Unfortunately, this increased can occur at the expense of carbohydrate combustion at high intensities.

A high FatMax means the individual can reach a higher fat combustion rate due to an LCHF approach, but they would do so only within a very narrow percentage of VO2max range (and wattage). In other words, if they step outside of that zone, they could run into trouble. A wide FatMax, on the other hand, means that the athlete may have a lower FatMax peak but can oxidize fats within a broader range of VO2max percentage and wattage—which makes sense given the fluctuations that occur during an actual race situation. That also means that the athlete still performs good fat oxidation at higher wattages without losing the ability to use carbs for high-intensity efforts that might occur. This is a term called “metabolic flexibility” (see this post from Aitor Viribay Morales for a deeper dive into the concept).

“For competition, you’d want a wider FatMax, as you’ll always burn a certain amount of carbohydrates if you’re at higher intensities,” said Robert Gorgos, former nutritionist for Ironman World Champion Anne Haug and nutritionist for the World Tour cycling team BORA-Hansgrohe. “And even in the FatMax zone, a medium-trained athlete can still burn 70-80 grams of carbs per hour (probably at around 200W). Four to five hours on the bike, would equal about 400 grams of carbs. If you’re more fat-adapted through a nutrition intervention, you may burn 40-50 grams per hour, so I don’t think the sparing effect is that huge.”

Gorgos believes that putting all the eggs in the LCHF basket can also be detrimental to the glycolytic system—the one that produces energy through the breakdown of carbohydrates (especially at high intensities). But he also says that cycling races are more geared towards explosiveness and higher powers than long-distance triathlons.

“I see the point that with certain nutritional approaches, you force your body to be a little bit more efficient and use a little bit fewer carbs, but I think the risk is too high to see the real benefit,” he said. “I don’t believe you can also win an Ironman, at least at the very high level, only using the fat-burning metabolism.”

Triathlon coach Laura-Sophie Usinger agrees—following both her personal experience as an athlete and coach as well as scientific evidence. “Carbs are the holy grail of our muscle fuel,” she said. “You want to have the ability to use them to support the exercise demand. If you eat low-carb and want to do high-intensity training or race at a high level, your performance would be compromised.”

She says that having low-carb availability would compromise both your high-intensity training and impair performances for at least 7-10 days from the beginning of the intervention and up to 4-6 weeks for some. From a health perspective, she says that LCHF in elite athletes has been shown to negatively affect the immune system and bone markers (making them more likely to experience stress fractures).

“Often LCHF goes hand in hand with low energy availability too—and that makes athletes gain weight instead of losing it,” she said. “That’s because with low energy availability, the body is storing as much as it can, and gaining weight is a result.”

But even Usinger believes that for some groups of athletes, LCHF can have some benefits, mainly if the athletes are overweight and want/need to lose body fat or if they’re athletes competing at very low intensities for 12+ hours. And of course, there are very successful examples that an LCHF approach for long-distance triathlon can be beneficial. Van Berkel is one of them.

So who’s LCHF suitable for?

Who Is LCHF For? You’re A “Van Berkel”

Before deciding if the LCHF approach is right for you, you ideally need to perform a metabolic test. That’s what Van Berkel and Plews did back in 2016 to understand his metabolic profile better and then checked his progress over the years. A metabolic test evaluates how athletes use calories at different intensities, and what percentage comes from fat stores versus carbohydrates.

Related: Test, Don’t Guess: Nutritional Tests You Need for Optimal Health And Performance

The first tests showed Berkel had a FatMax of 0.76 g.min-1 at a power output of 160 watts. Because of this, Plews had no doubt he would hugely benefit from an LCHF approach. In 2017, Van Berkel finished the IM WC in 22nd place (in 8:38:48). In 2018, he won IM Switzerland in 8:09:18, went under 8 hours in Texas (7:48:40), and clocked a personal Kona best of 8:27:03—a time he improved again in 2019 with 8:17:04 (where he finished 11th place).

The test they had performed in January 2019 confirmed the progress: His FatMax had gone up to 1.24 g.min-1 (now at 220 W), and his fat oxidation at 250W (close to his IM goal wattage) went from 0.62 in 2016 to 1.08 g.min-1 in 2019. That corresponded to fat producing 37% of his energy in 2016 to now producing 70% in 2019. This year, he went under 8 hours again at IM Tulsa, placing second in 7:50:58 behind two-time Ironman World Champion Patrick Lange (7:45:22).

Who Is LCHF NOT For? You’re A “Lange”

But then if you look at Lange, who is also a vegetarian, you have the proof that, a higher carb consumption works quite well too.

[My nutritional approach is] well balanced, I would say. The more intense I train, the more carbs I eat…I also check my macronutrient status every three months with a specific blood test. If there is a specific need, I can adjust my diet.

Lange also says that he has never experienced issues with his nutrition and never experienced a bonk during races. Yet, he sometimes trains with lower-carbs during morning swims or runs. “[During these days] I stay at an easy pace and avoid too much intensity. On the evening before a low-carb training morning, I try to keep carb intake low too.” This protocol (the “train low” one) is well established in endurance sports and aims to increase fat-burning capacity and fat as a fuel. It’s particularly common among some cyclists.

The Best of Both Worlds

The “train low” approach may be the best of both worlds, and even Gorgos uses it with his athletes. Without a professional helping you closely and without a metabolic test, this is perhaps the safest way to implement some low-carb approaches into your training—without getting too extreme and still retaining a good carb intake on hard days.

“Train low days are not very common, and we probably do them once a week and not during the competition phase, but during the preparation period, because it takes quite long to recover from it,” Gorgos said. (The timing of the LCHF approach is also very important for Plews, who implements it with his athletes very early in the preparation phase.)

Gorgos explains that “in a normal train low approach, you would do a training block of two-to-three days. On the first day, you’d perform at the highest intensity to deplete the glycogen storage. On the second day, you’d do tempo training (or medium intensity), and that would deplete glycogen even more.”

Then, at the end of that second day, you would not fill up the glycogen stores completely (including during and after the session), which means consuming lower carbs for the rest of the day. The third day’s breakfast would also be lower on carbs and higher in fat (an omelet with veggies, for example). Breakfast would be followed by the long training sessions performed at lower intensities and lower on carbs too: water only, or water and electrolytes at the beginning of the session. Finally, you can add some more carbs at the end of the session (or use products with slow-release carbs) and replenish the carb stores as you finish.

However, one thing is equal in both approaches (lower and higher carb): training and racing are two different pairs of shoes, and even LCHF athletes ramp up their carb consumption on race week and during the race.