How the Triathlon Wetsuit Came to Be

(Photo: Patent, Dan Empfield, Paul Phillips)

The neoprene wetsuit as we know it—all sleek black lines and buoyant warmth—first appeared in the 1950s and helped bring surfing, free diving, and other cold water activities to a broader audience. Surfing legend Jack O’Neill, Body Glove International co-founders Bob and Bill Meistrell, and physics professor and Manhattan Project scientist Hugh Bradner have all variously laid claim to being the first to invent the neoprene wetsuit, which traps a thin layer of water between the suit and the skin that’s warmed by body heat to create a cocoon of comfort on the high seas.

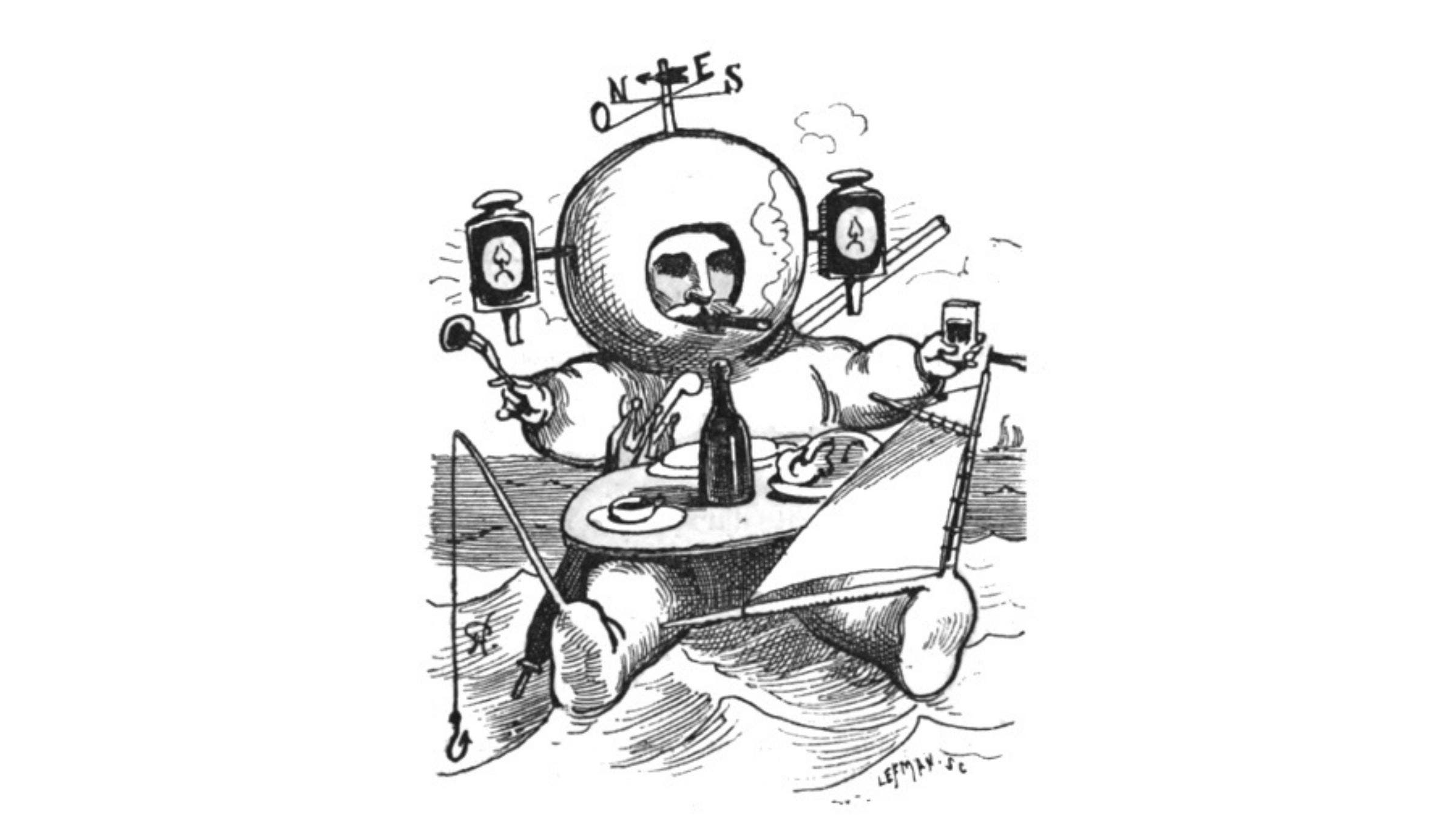

But the concept of the wetsuit has earlier, pre-neoprene origins stretching all the way back to the 1870s. Captain Paul Boyton, an Irish-born American merchant seaman and something of an early template for P.T. Barnum, founded a lifeguard service in Atlantic City, New Jersey. There, he became acquainted with C.S. Merriman, a Pittsburgh-based inventor who’d created a waterproof, life-saving rubber garment filled with inflatable chambers.

In his 2009 book, Young Woman & The Sea, sports historian Glenn Stout writes that Boyton’s suit “was capable of supporting 300 pounds, a man, and up to nine days of provisions stored in a special pouch. The wearer of the suit carried a paddle to propel himself through the water, and it was even possible to attach a small sail to an iron hook that protruded from the sole of one of the suit’s rubberized feet.”

The suit “was capable of supporting 300 pounds, a man, and up to 9 days of provisions stored in a special pouch. The wearer of the suit carried a paddle to propel himself through the water, and it was even possible to attach a small sail to an iron hook that protruded from the sole of one of the suit’s rubberized feet.”

Boyton used this archaic drysuit-wetsuit contrivance to float across the English Channel and stage a series of other extraordinarily long float-swimming events to promote water safety. But as useful as Boyton’s so-called “frogman skin” was for keeping the wearer alive in cold water, it was stiff and cumbersome—making it impractical for extensive water activity (like swimming).

Then, in 1930, research scientists at the DuPont chemical company invented a new, highly flexible and durable synthetic rubber. Derived from petroleum, neoprene demonstrated superior heat retaining and buoyancy-aiding properties while being comfortable and easy to use in garment manufacture. Surfers loved it, and neoprene has remained the preferred material for manufacturing heat-retaining clothing ever since.

Does the wetsuits-are-faster hypothesis hold up?

Wetsuits, then, were largely a comfort and safety tool for diving and surfing, without too much thought given to swimming speed—until triathlon. As our sport grew and experimented with equipment in the 1980s, athletes saw how surfing’s uniform could help boost speed and comfort in the water. At the 1986 Bass Lake Triathlon, Dan Empfield noticed a handful of swimmers wearing the thick neoprene suits and had an a-ha! moment: “The water was cold, we were standing in our Speedos in snow waiting for the gun to go off. Professional triathletes Scott Tinley and Gary Peterson swam in what appeared to be just their surf wetsuits, and they didn’t swim slow.”

Empfield then used the surfing prototype to build a thinner, more pliable model suited for swimming (which went on to become the company Quintana Roo), and the triathlon wetsuit was quickly adopted by open-water swimmers everywhere looking for warmth and—more importantly—speed.

So exactly how much faster does a wetsuit make a you? That’s actually yet to be quantified.

Dr. Sean Newcomer, a kinesiologist and researcher focusing on the science of wetsuits from his lab at California State University San Marcos, said that “from an academic standpoint, there’s not a lot of research” about wetsuits and how they assist performance. “Manufacturers do some testing, but how scientifically rigorous it is is somewhat questionable because they just don’t have the facilities or knowledge base to do the types of studies needed.”

Newcomer and his CSUSM colleague Jeff Nessler, also a kinesiologist, are trying to add more rigorously scientific data to the discussion. But Newcomer says this research is a still-nascent field of inquiry that presents a lot of challenges.

“The problem with field studies is you can’t control variables,” Newcomer said. And environmental factors, such as wind speed, air temperature, and water movement all play a big role in how fast a swimmer will be over a specific course from one day to the next.

In an effort to collect more controlled data, his team also uses an Endless Pool in their lab where they can connect test subjects to various instruments to make more precise measurements than they’d be able to collect in the field. Over a number of studies, Newcomer’s team has measured thermal regulation and oxygen consumption along with other physiological data points for wetsuit wearers in action. In other simulations, they’ve placed test subjects on a Vasa dryland swim erg machine and measured different physiologic outputs outside the water.

The race to build a faster wetsuit

Though the surf lab has been analyzing wetsuits mostly through the lens of surfing, there are some extrapolations that can be made for triathlon. And some of the findings are already being implemented by wetsuit makers who’ve been tinkering with their designs to find the optimal fit and performance for their customers.

Orca is one such company. Founded more than 25 years ago by New Zealand triathlon champion Scott Unsworth, Orca was another one of the early companies making wetsuits specifically for triathletes—meaning they’re focused on making the fastest wetsuits they can.

To do that, Iñigo Pereda, a member of Orca’s product development team, said Orca starts its design process by collecting and analyzing user feedback and looking for potential new ways to meet their needs in open water. They continually try out new materials and designs and conducts lab-based tests to measure various characteristics of a material before incorporating it into a design. They’re looking at elasticity, thermal insulation, and hydrodynamics performance, while also conducting buoyancy and UV exposure tests.

If the material passes those tests, a prototype is generated and sent out to athlete ambassadors for wear testing. The company then collects their feedback and compares “the numbers we get in the lab with the natural feeling of the product,” as reported by the testers, Pereda said.

Not every prototype makes it past this roadblock. “Unfortunately, some concepts don’t work or cannot work with the current technology,” he said. And sometimes a great design just doesn’t feel right in motion.

That lack of real-world comfort is what led to the founding of another well-known triathlon wetsuit brand, ROKA. Co-founders Kurt Spenser and Rob Canales, two All-American swimmers from Stanford, had begun dabbling in triathlon a decade after graduation. But they felt the wetsuits they found in the market left a lot to be desired for serious swimmers.

Michael O’Neil, VP of marketing strategy and analytics, says the company continually strives to create suits that make wetsuited swimming feel more natural. “I always thought swimming in a wetsuit felt like paddling a surfboard,” O’Neil said, mimicking the high, wide sculling motion of a surfer searching for the next swell.

After some investigation, the ROKA team discovered that placement of neoprene thickness in other suits was largely to blame for the changes to body alignment that they felt hindered their practiced swimming stroke. They thinned out the neoprene along the trunk to help restore some of that natural motion in their own design.

“Swimming is all about rotation, and your power comes from your hips,” O’Neil said, so that design insight led to dramatic functional improvements in the suit.

“A few prototypes later, we decided ‘this is better than what’s out there already.’”

This alteration echoes some of Newcomer’s research findings. “The thicker the neoprene, the greater the amount of resistance you’ll see from that neoprene. This means you want to keep the neoprene as thin as possible, but it has to be thick enough to keep your core temperature normalized” and to keep from shredding when it’s taken on or off. “It’s a balancing act,” he said.

Subsequent iterations of ROKA’s wetsuit line have featured additional innovations, with perhaps the most notable being the idea to change the pattern from which the suits are initially cut.

“Wetsuits had always been designed the same way apparel has been—with the arms at their sides,” O’Neil explains. But the ROKA design team wanted to see what would happen if they started with the arms up, as though the wearer were swimming with a tight streamline as the foundational position.

“There were a bunch of details to figure out in that pattern to make it work around the neckline,” O’Neil said, but eventually they created a workable prototype.

The first time he put it on, O’Neil says his arms felt like “when you did that thing as a kid, where you stand in a doorway and push the backs of your hands down against the doorjamb for a while and then walk out and your arms sort of float up on their own. It has that same feeling.”

Has this design change resulted in faster times? O’Neil notes that it’s “hard to measure” how much faster a wetsuit can make a swimmer, especially when testing in the field where so many variables come into play.

“You’ll hear anecdotal examples of people saying, ‘this bettered my 1500 time by two minutes,’ and we love to hear that, but it’s probably not all the suit,” he said. “Give the engine or the conditions or the course measurement some credit, too,” as small variations in those factors from race to race can make an enormous impact on how fast you swim.

RELATED: How Much Faster Does a Wetsuit Make You Swim?

From design lab to diving in

In triathlon, a wetsuit is considered a success if it shortens your swim time or limits your energy expenditure so you exit the water fresh and ready to crush the bike and run. Here, too, there’s limited hard data to suggest one suit is better than another—it usually comes back to trial and error and user preference.

Still, Newcomer says that wearing a wetsuit does seem to make virtually every user at least a little faster. Some of that result may be similar to how a knee or wrist brace works to prevent injury—the gentle pressure the brace exerts on the skin helps the body better perceive where it is in space. “Wetsuits, like braces, provide proprioceptive feedback that allow you to have a greater understanding of where your joint is so that you don’t put the joint into a situation that would potentially cause greater injury.”

That external pressure from a wetsuit can also act like a giant compression sock on your whole body, stabilizing the core and reducing the fishtailing motion that many less experienced swimmers display. The added buoyancy in the lower limbs improves body position, which can also improve swimming efficiency.

There’s also a mental boost to wearing a wetsuit for some swimmers. “Some people are afraid of what’s in the water, and having 2 millimeters of neoprene helps them feel protected from interacting with animals in the water,” Newcomer said.

For others, that mental boost comes from looking and feeling sleek and ready for battle. Ginger Reiner, a long-time age group triathlete based in Lincoln, Massachusetts, says wearing a wetsuit that fits well gives her “a feeling like water is sort of running past. I feel very hydrodynamic.”

Over the 21 years she’s been winning triathlons, Reiner said she’s owned two wetsuits. Her current suit, a Zoot that came from a brief sponsorship she had years ago, is “on its last legs. I’m literally gluing it back together to continue to work.” While she generally doesn’t prefer swimming in a wetsuit, she says she likes the fit of this particular one because the neoprene is thinner in the shoulders and arms and thus doesn’t restrict her movement as much as others she’s tried in the past.

RELATED: How to Make Your Wetsuit Last Forever

There’s no such thing as free speed

Despite all the effort that’s gone into making wetsuits a high-tech piece of kit, donning a neoprene garment isn’t the only means of achieving speed and efficiency improvements. Good old-fashioned hard work may offer an even bigger impact, said swimming coach Jen Dutton, an accomplished marathon swimmer who works with many pro and age-group triathletes.

“Wetsuits do provide swimmers with a sort of ‘exoskeleton’” that supports the core and improves body position, she said. But “the good news is that by engaging core muscles and incorporating proper timing, swimmers can make their own balance. Body position and line can always be improved by using a pull buoy, fins, or a wetsuit,” she said.

Or, you can also achieve those results by “putting in some time and learning to make subtle adjustments” through technique drills and consistent training.

Reiner agrees that while her wetsuit does make her feel sleeker and more efficient, “I don’t think it’s as much of a help as going regularly to the Masters workouts” that Dutton coaches.

Practice makes perfect, after all, so while you can certainly plunk down oodles of cash in pursuit of some “free” speed, maybe making sure you’re doing all your homework in the pool is another scientific way of tapping into a faster swim.