Review: Gazelle Wearable Technology System

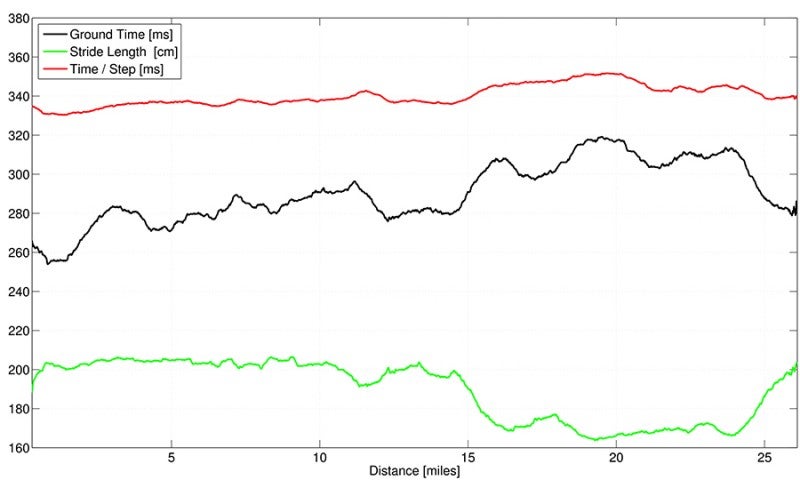

Depicted in this graph is some of the gait analysis data collected by a pair of Gazelle foot pod microchips the author wore while running 26.2 miles to complete an Ironman triathlon on Aug. 3 in Boulder, Colo.

The soon-to-debut Gazelle wearable technology system can help runners improve their gait and efficiency in real time on the move.

Wearable technology is all the rage in running right now, and with good reason. New technologies in smaller, lighter and more portable applications are making it easier to track and analyze the basic data of a run (time, speed, distance, pace, elevation change, etc.). It’s a competitive arena, with Timex announcing its new One GPS+ smart watch on Aug. 6 and Apple apparently about to launch its iWatch when it releases the iPhone 6 next month.

But one of the most amazing next-generation wearable technology applications will be coming soon from an upstart technology company called Athlete Architect in Boulder, Colo. It’s called Gazelle, and it’s the one of the first wearable applications that can track sophisticated running gait data in real time during a run or race and help runners improve their form during a run. (There are other start-up companies working on similar systems, but this one appears to be on the very leading edge.)

How does it work? Using a customized chip that monitors foot movements in a three-dimensional plane, the Gazelle foot pods can track the angle in which a foot impacts the ground, the time the foot is on the ground and in the air and even the impact of footstrike to determine how efficient a runner’s gait is. When wearing headphones and carrying a smartphone synced with the Gazelle user-interface app, runners can get audible coaching cues on how to adjust their form during a run. (You can also collect the information on the foot pods and wirelessly download the data after a run or race.) Gazelle also tracks everything else that a typical GPS watch can track—for example, time, distance and pace—plus dozens of other data points.

Three weeks ago I participated in Ironman Boulder wearing Gazelle chips on my running shoes. After a rough swim and a hard bike leg, I wasn’t sure I’d be able to run at all. But I found my legs a bit and, amid some struggles, wound up running a 4:30 marathon split. It’s not what I hoped for, but given that my legs were toast by Mile 16 and I had to summon every ounce of energy I could to keep running (albeit slowly) to the finish, I was plenty happy with the results. I didn’t run with a real-time tracking app and headphones (Ironman forbids headphones!), but in examining the data afterward, it’s obvious where I started to become less efficient and the time my feet spent on the ground increased.

(On two previous wear-test opportunities earlier in the development cycle, I did experience the audible coaching cues while wearing headphones connected to a smartphone strapped to my arm and was impressed with how quickly the chips sensed the slightest changes in my gait.)

A graph that illustrates some of my gait data (above) shows my strides got shorter during the second half of the race, but when comparing that to other metrics (including running pace and the time my foot was on the ground), it’s clear my gait wasn’t getting more efficient. It was actually getting much less efficient as I fell into the survival shuffle mode common to many mid-pack triathletes, ultrarunners and marathoners. Had I run with the app and my smartphone, I could have used the data and audible cues to improve my form and efficiency on the fly. As a lifelong runner, I know that simply lifting my lead leg higher to start a stride and quickening my cadence would have helped, but when you’re as cooked as I was in 85-degree heat, that’s the last thing that was on my mind.

RELATED – 2014 Triathlete Buyer’s Guide: Run Computers

“Our goal is bringing the technology to the real world,” says Li Shang, president of Athlete Architect. “Sports physiologists can test runners in an indoor lab with a fancy treadmill setup, but that’s not the real world. There are limitations and variables in the real world, but there is a lot that can be learned by tracking a runner during a workout or a race.”

The Athlete Architect technical team dismantled competing products already in the marketplace to determine how they could push Gazelle even further than those. Ultimately, it decided to push way beyond the current consumer protocols and instead aimed to create a portable device that could mimic a sophisticated gait lab like the one at the University of Colorado. It is also developing a power meter for the Gazelle system (believed to be the first portable/non-laboratory power meter for running), something that could be a real game-changer for runners.

“With a power meter added into our system, a runner can know exactly how much power they’re producing. And combined with the stride and gait information, that’s when you can really figure out how efficient you are during a run,” says Gus Pernetz, sports business engagement director for Athlete Architect. “You can change your behavior while you’re running to become more efficient, just as you would if you were reading a power meter while you’re cycling.”

One of the initial goals for Gazelle was to be able to create a system that would be comparable to a 3-D motion tracker in a laboratory setting, says Wyatt Mohrman, one of the lead engineers behind the development of Gazelle.

“We started with running first because there are a lot of interesting results you can get from tracking a runner. And what you can see from the data is that every runner is completely different,” Mohrman says. “But once we get additional data from runners, we’ll be able to compare runners who are more similar than others—for example by the same height and weight or the same pace or cadence. We want to have a big community of runners so you can look at yourself with a more refined group of runners who are like you and then also compare yourself to different runners. So if there is a community picture, runners can start to realize those things on their own and make adjustments to their own running.”

Gazelle isn’t available in stores yet. Instead, the company has seeded its tracking chips to about 30 key coaches and runners for final beta testing and feedback. (Two other runners were tracked during the Ironman Boulder.) The team at Athlete Architect believes its hardware and signal processing technology are pretty buttoned-up, but it hopes to use the feedback from those test subjects to be able to fine-tune the user interface and focus on the appropriate metrics the system tracks. (Each chip is powered by a long-life battery that is rated to last from several months to a full year under normal everyday use.)

From there, the brand intends to launch a KickStarter campaign to raise money in order to commercialize the product. It already has a production system set up, so it probably won’t be too long before runners can buy it.

Shang is quick to point out that technology, in general, has limitations, including the Gazelle system. While the information tracked on the system will provide useful insights to help a runner improve performance and efficiency, it won’t remove the need for coaching input or the runner’s physical and mental effort while running. If anything, it will enhance those functions, Shang says.

There are dozens of possibilities in which the Gazelle system could be useful. For example, a coach could analyze the data of a runner’s workout or race and determine where a gait flaw can be improved through strength-building exercises and form drills. It could be built into a shoe and offered as a package deal for runners. Also, a version of the product could also wind up assisting retail stores in accurately determining the gait habits of individual runners and how those habits are affected in various shoes during the try-on phase. (In other words, it could make obsolete the already very limited functionality of the basic gait analysis operations many running stores employ with video cameras and treadmills.)

“What will it mean to fully realize the potential of the technology? We have no idea,” Shang says. “We just don’t know. But the potential of the technology cannot be realized only by engineers. We can put other sensors on this device and track even more information, but the new discoveries can only happen by working with the experts—sports physiologists, coaches, runners, shoe manufacturers. I think what we’ve done is only about 49 percent of the job. The other 51 percent will come from them.”