What Is an Internally Shifting Hub (And Why Are Some Top Pros Using It)?

In a given training ride, you might shift your gears dozens of times without giving it any thought (assuming your bike is well-tuned). And by most measures, aside from the recent introduction of electronic shifting, not much has really changed. Sure, there are more gears than ever, shifting faster and smoother, but bicycle drivetrains have endured more than a century of refinement to get to the modern systems in use today, and most, if not all, are conceptually similar.

While there is a great deal of variability among drivetrains across different cycling disciplines, pretty much every competitive bicycle uses similar shifting componentry that all hinges on externally mounted derailleurs shifting gears.

But a new paradigm has begun to emerge that stands to turn that tried-and-true model into a thing of the past. There are now entire drivetrain systems that use internal gearbox shifting that proponents hail as a golden bullet to cut down on maintenance and protect the part of the bike that has traditionally had the highest chance of breaking.

While these transmission systems can seem a world away from the ultra-light, aero-centric world of triathlon, they are much closer than many might think.

A similar type of this tech has recently been spotted among the cream of the crop of professional triathletes. Kyle Smith of New Zealand and Ruth Astle of Great Britain both sported a sleek-looking Parcours disc wheel outfitted with Classified’s internally geared Powershift hub at the PTO European Open and World Long Distance Triathlon Championships in Ibiza back in early May.

The hub is nothing new. But its application in the professional triathlon community is. So, what is it?

Internally geared hubs, as their name would suggest, house shifting mechanisms inside, rather than externally. Some, like those made by Shimano, Sturmey-Archer, RaceFace, Enviolo and other geared-hub manufacturers, contain a full range of gears that completely replaces front and rear derailleurs.

The latest example—the first one that’s truly found a home on triathletes’ rigs—is Classified’s Powershift system. Though it’s not a complete drivetrain, it’s one that allows riders to experience the wide gear ratios of a traditional 2x setup (one with a front derailleur that shifts between a big and small chainring), with the efficiency of a 1x setup (no front derailleur).

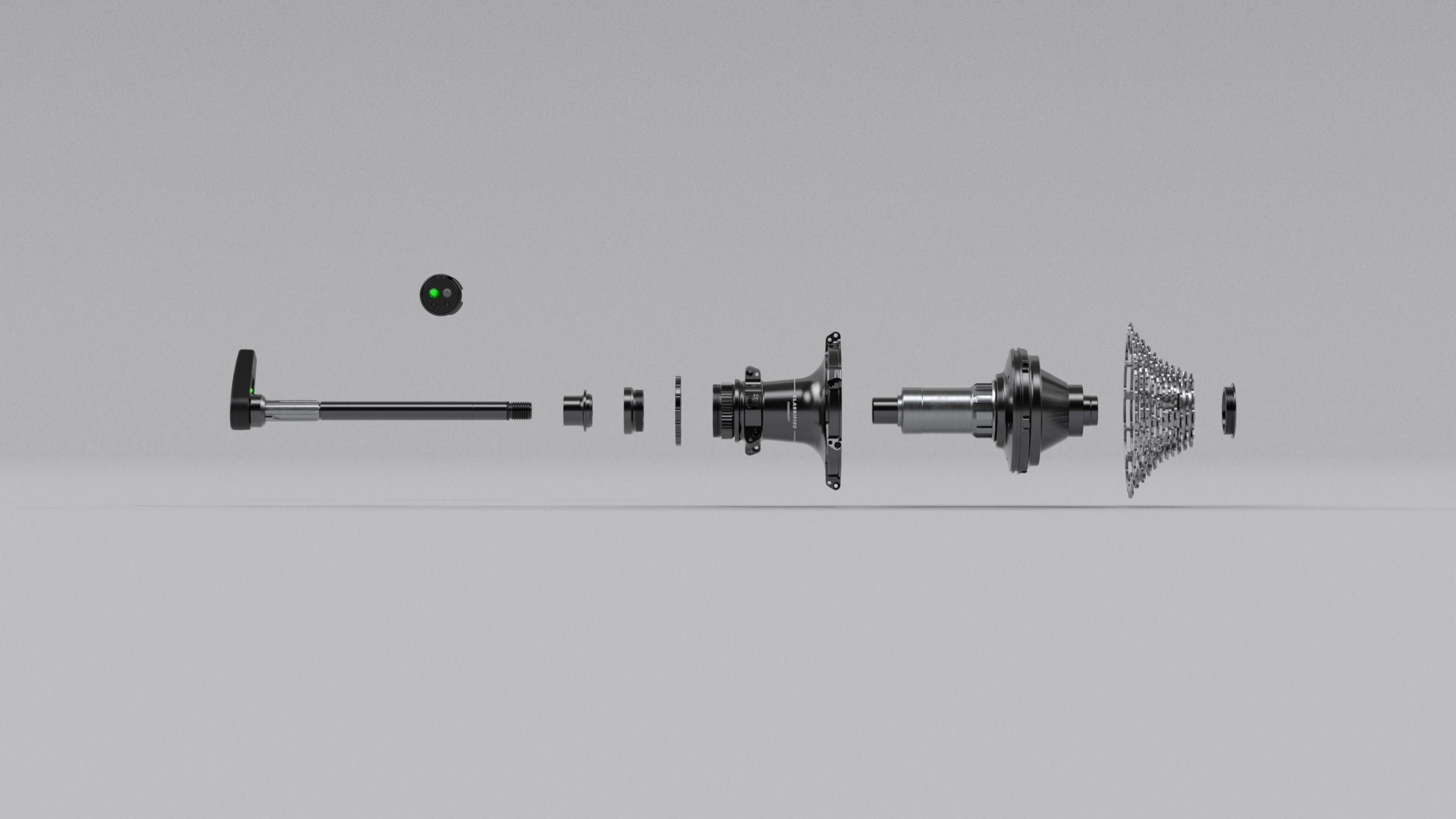

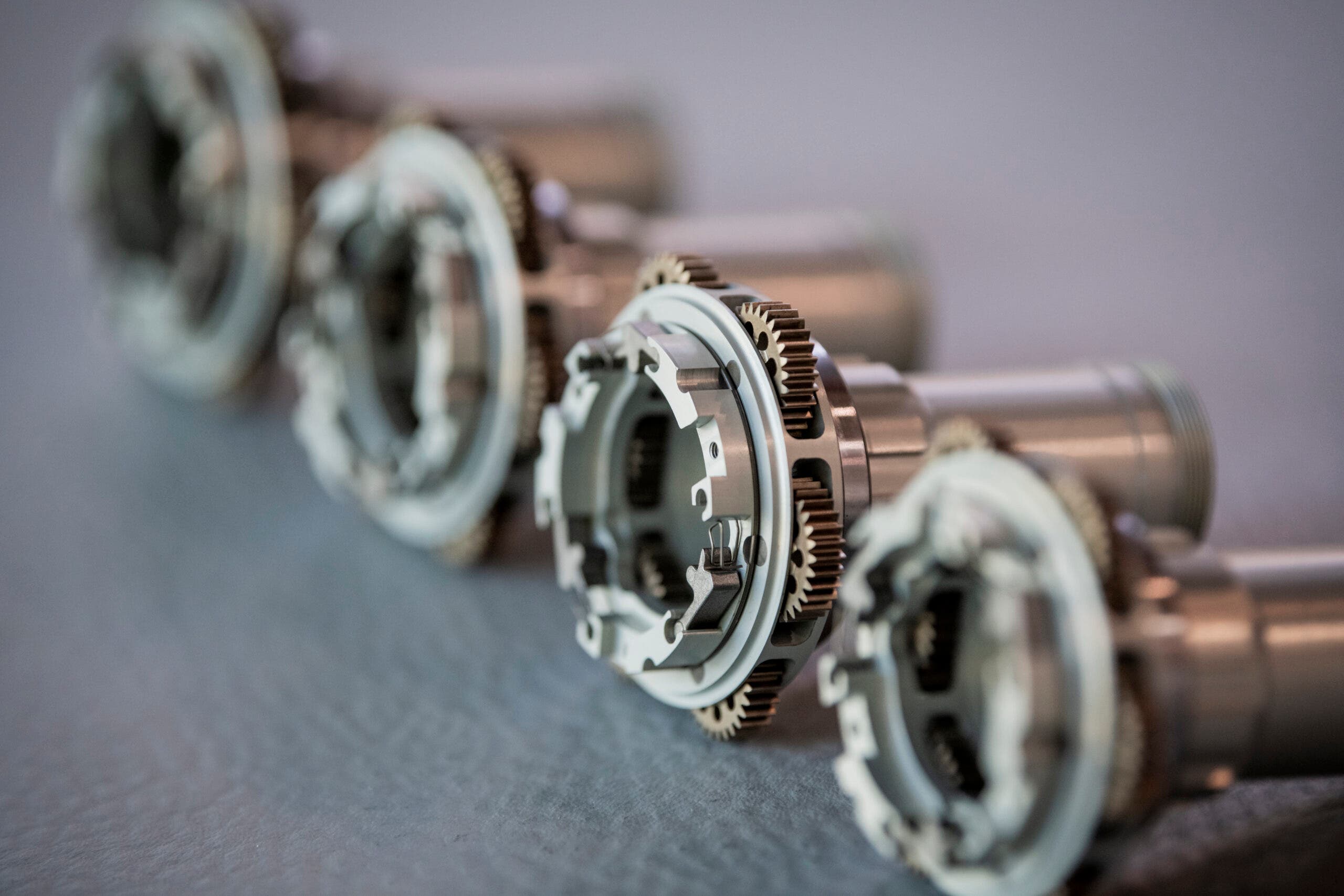

Powershift houses two planetary gears inside of the hub. Think: One center gear with three “planet” gears circling it and helping drive a larger gear outside. The smaller gear, also known as a “sun” gear, is positioned inside a larger gear with planetary gears filling the space in between. A wireless signal delivered through a smart thru-axle travels through the system to tell it which gear should be rotating.

Rather than running a chain up and down a cassette, all of the shifting components work together at the same time, allowing some parts to move freely while others stop when switching from gear to gear.

For example, the larger gear on the outside moves at a 1-to-1 ratio, meaning the wheel moves at the same speed as the cassette. When the smaller gear, which has a ratio of 0.686, is engaged, the cassette spins faster than the rear wheel, explained Yannick Mayer, Classified’s technical marketing manager.

The resulting effect mimics a 2x system with which most riders would be intimately familiar. Wheels still can operate with a full 12-, 13-, or any other speed cassette, but the big gear shifting, what riders would usually do on the front chainring, happens out back too, albeit inside the hub. No front derailleur required.

Also, unlike traditional systems, Classified says its Powershift technology allows riders to shift with rapid speed under a full load (no letting up on the pedals to shift, like with a finicky front derailleur), and with a gear ratio and weight that are competitive with other high-end traditional drivetrain components.

Mayer said those key features, along with the ability to use a larger chainring and eliminate drag from a second chainring and front-derailleur, make for a cleaner and more efficient ride—something triathletes looking for that aero-at-all-costs setup will appreciate.

“For triathlon, we see a special use for those bikes that have to be super aerodynamic and are built for a speed and losing as little power as possible on the bike leg of a race,” he said.

Mayer claims that taken together, running a single chainring with the Powershift system gives riders about a 1% gain in efficiency.

Since the gears don’t shift by moving a chain a considerable distance from one chainring to another, the shifting feels immediate and reliable, even under load. With traditional systems, shifting under power can rip a cassette apart, break a chain, drop a chain, or at least create a lag in power delivery as the chain moves into the correct position.

The Powershift system is not unheard of in road cycling, but it is rare. It has become a bit more common in the gravel world, likely due to its ability to protect sensitive gearing components from nasty gravel elements, cut down on maintenance, and clear up issues with chain crossover that can easily happen when jumping from ring to ring at the high and low end of a cassette.

While new to triathlon, Classified hubs are making inroads. Parcours, which recently went public with the afore-mentioned Powershift-ready disc wheel spotted under Smith and Astle, says the combination gives athletes the most efficient setup possible, allowing them to hold onto more energy and comfort over longer distances.

“Powershifting reduces the time to shift (150 milliseconds) in critical race situations, so the rider can keep pedaling when others cannot, without the possibly race-ending risk of a dropped chain,” Parcours said.

For those who need proof, Astle picked up the fastest bike split at the race in Ibiza.

“It is the ability to just shift so quickly under load, which is really helpful, particularly on courses with steeper climbs,” Astle said. “But the ability to always run a bigger chainring up front dramatically increases the efficiency of the bike even further. It just makes me go faster!”

Traditionally, the lack of maintenance has been the main draw to internal gearing, but for the ultra-aero needs of triathletes, efficiency gains may prove even more consequential, provided the trend takes off. Whether that will happen, though, remains to be seen.

Avery Arrendondo, a sales and service representative at the Velorangutan bike shop in Austin, Texas, said he’s seen internally geared hubs come through the shop, but more on the mountain bike and commuter end of the spectrum. Velorangutan specializes in high-end mountain bikes and custom builds, which is where some of this tech tends to show up.

Arredondo said hubs and drivetrains with internal gearing typically require less maintenance than traditional drivetrains, and can also last longer, especially those that are belt-driven, as opposed to chain-driven—though there are no belt-driven applications in tri yet. However, these systems, while requiring less maintenance, can also be difficult to get inside and work on if something does go wrong, Arredondo said.

“Depending on where you are, it also can be hard to find someone with the skill set to work on them,” he said.

Many manufacturers of internally geared hubs, Classified included, claim that they are basically maintenance-free, except for the need to occasionally reapply oil. If more pros hop onto the internal-gearing bandwagon, it could very well spark wider adoption among age groupers and other tech-oriented athletes.

Classified hubs retail starting at about $1,400. The Powershift-ready Parcours Disc2 wheel ranges in price from about $1,200 to $1,700.

For the sneaky tech nicknamed “the front derailleur killer,” the recent foray into triathlon could be the beginning of something much bigger.

RELATED: Ask A Gear Guru: What Is A 1X Drivetrain? Should Triathletes Try It?