Expert Tested: The Water Bottle/Jersey Trend Produces Shocking Results

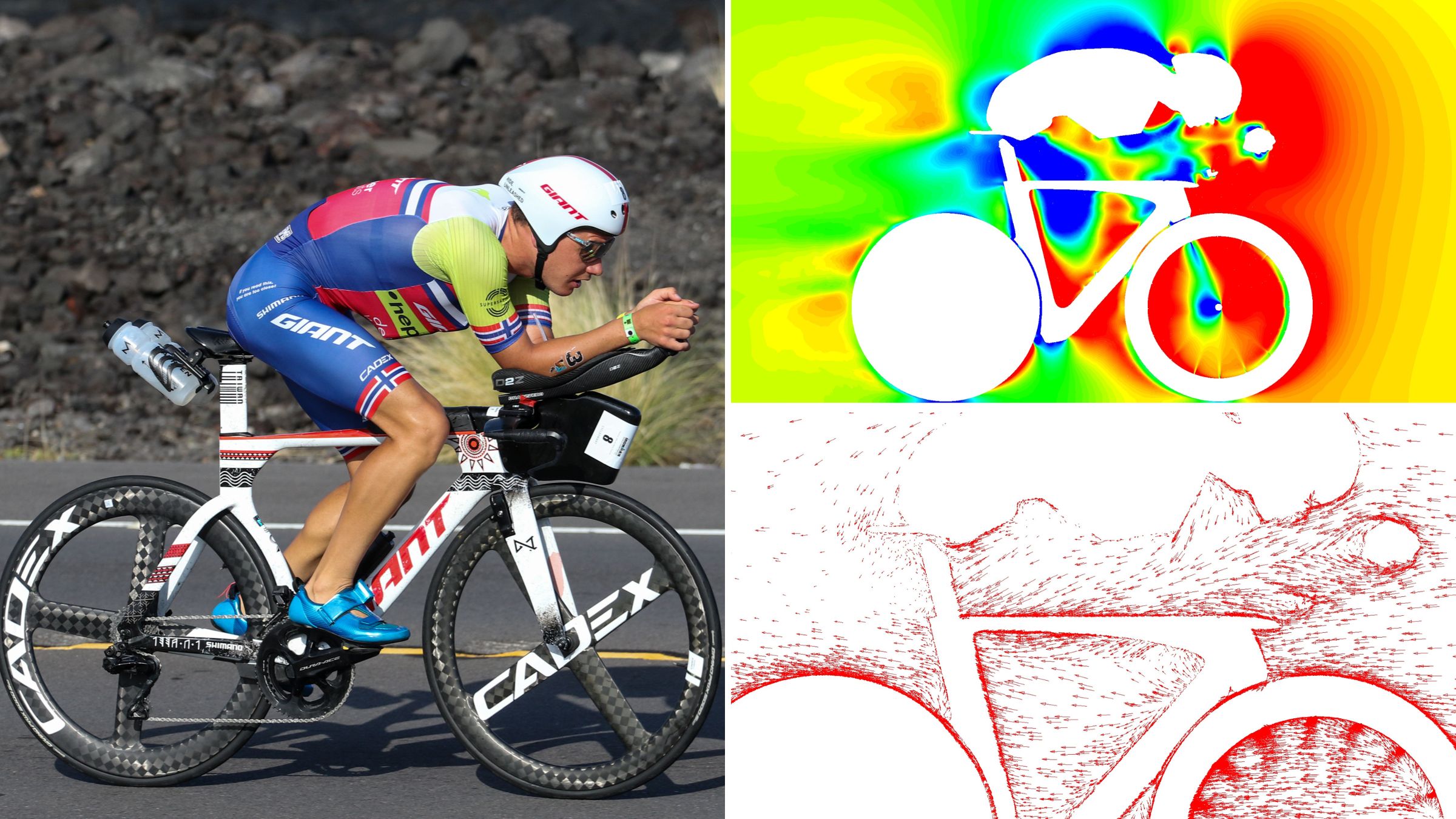

Is a water bottle down your triathlon jersey an aerodynamic advantage? (Photo: Professor Bert Blocken and Dr. Fabio Malizia of KU Leuven, Brad Kaminski/Triathlete, )

As trends go, stuffing a water bottle or hydration reservoir down your jersey or skinsuit might seem as aerodynamically cutting edge as lacing your cycling shoes up tighter to reduce wind resistance. But over the last year or so, race photos and footage have shown more and more professional athletes adopting the tactic—but to what effect?

Some use a simple water bottle, while others have been seen cramming what appear to be inflated bladders into their jerseys. All of them, however, say it gives them a critical aerodynamic edge on the bike.

While this “chest fairing” is still a newer trend, emerging research shows that, when done right, it can pay off in hefty dividends even greater than ever thought possible. But as more and more triathletes begin to sport the controversial chest fairing, two glaring questions remain: First, does it actually work?

And will it remain legal?

Jim Manton, owner of Southern California-based ERO Sports and avid aero-tester, is among a handful of people who have put the chest fairing idea under a microscope. Manton said that before he began testing the fairing idea on his athletes, he thought it was more of a gimmick than a silver bullet.

“It kind of shocked me to be honest with you,” he says. “I really did not expect to get the results we got. I thought it was a joke. I really did.”

Manton took nine athletes of different body types, sexes, and physiques and outfitted them with a few different types of bottles to stuff down their shirts and see what happened. He documented the process in a YouTube Video for ERO Sports called “Fast or Fiction: Does a bottle down the front of your kit make you more aero?”

Across the board, the bottle worked, albeit with several key nuances that are critical to its success.

“The one bottle that we have found to work on everybody is a 28-ounce, normal water bottle, and you keep it up high. You don’t put it down in your stomach. You keep it up high on your chest, and that’s when it works.”

Manton said the 28-ounce water bottle is small enough to fit riders of pretty much every shape and size, but larger 1.5-liter bottles, think of a large water bottle you’d buy at a gas station, work even better for those with a long enough torso to accommodate them. For those who can’t, they can be more of a detriment, as can larger bladders.

Manton said this is because bladders create more of a flat or rounded shape on the chest, rather than something that comes to more of a peak—the ideal shape to increase aerodynamics.

Bladders also take more time to get into position, which could result in further time losses without a lot of practice. Likewise, those with low collars on their kit could create a parachute effect if the bottle opens the collar up too much. But if done right, the chest fairing works.

“It’s been really fascinating to do,” he says of the testing. “I think, you know, 5% to 7% (drag reduction) is kind of what you see more often, but every once in a while you’ll see more on some athletes than others.”

In one example, Manton said, one athlete saw a 5.4% drag reduction.

“For this particular athlete and the wattage they put out, that was a savings of 12.4 watts. And so we would estimate over an Ironman that that would save right around two minutes,” he says. To put it in perspective: The winner of last year’s Ironman World Championship, Norway’s Gustav Iden, won by two minutes; third place’s Kristian Blummenfelt was less than a minute behind Sam Laidlow in second.

Preliminary results from Manton’s experiment showed that those with a more upright posture may benefit even more, but he hasn’t been able to do enough testing to really nail that detail down yet.

But other researchers are finding similar results in a lab setting.

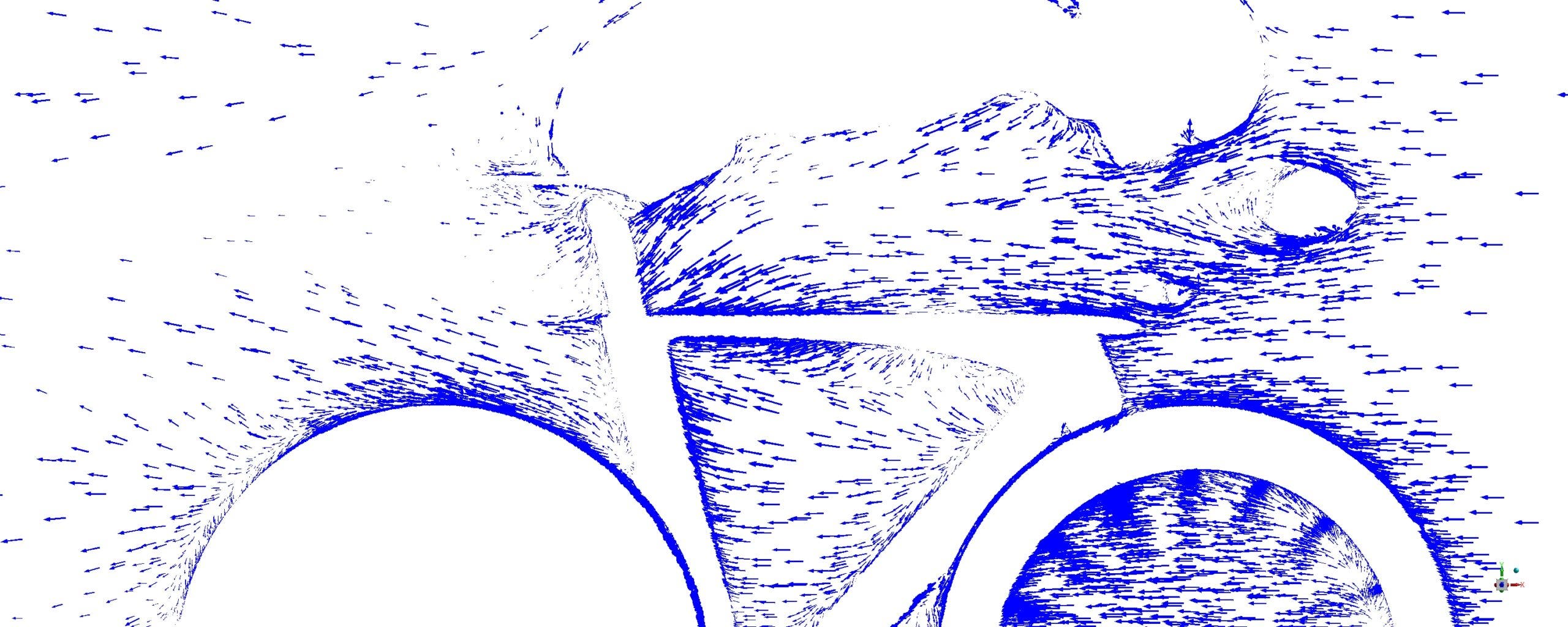

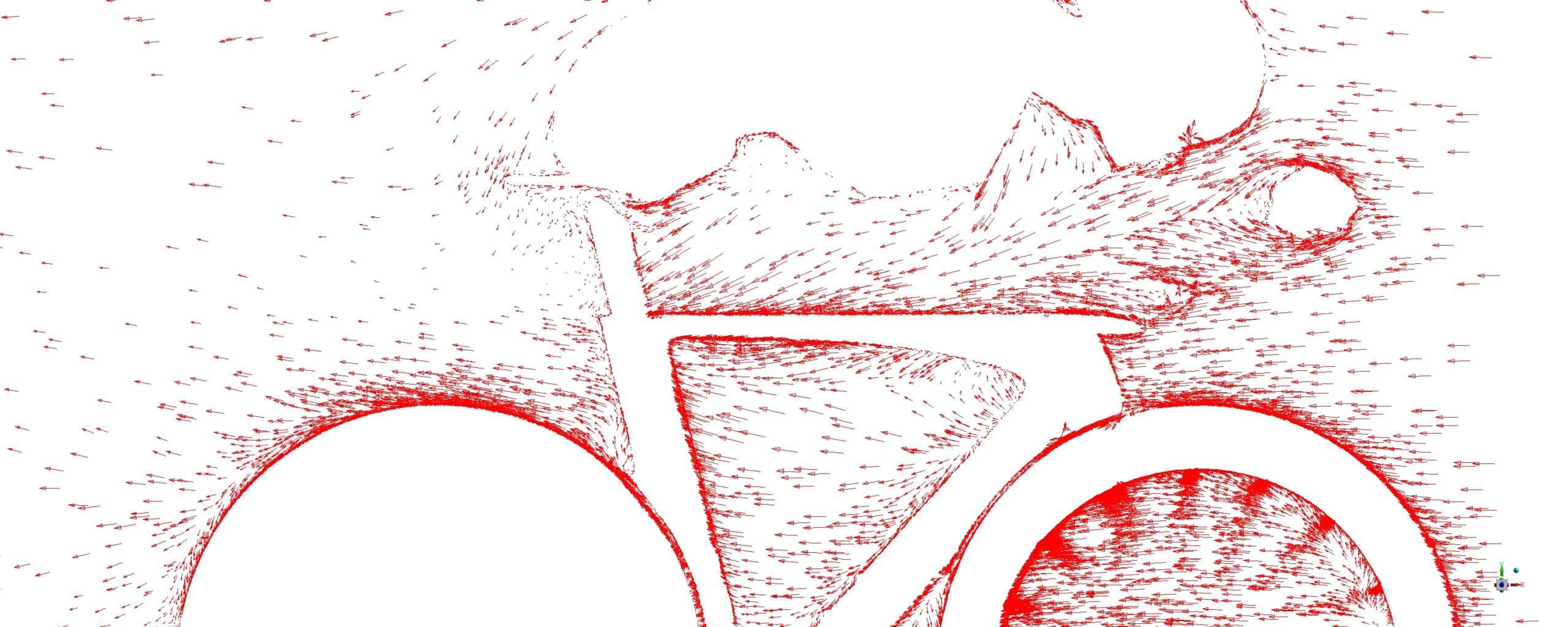

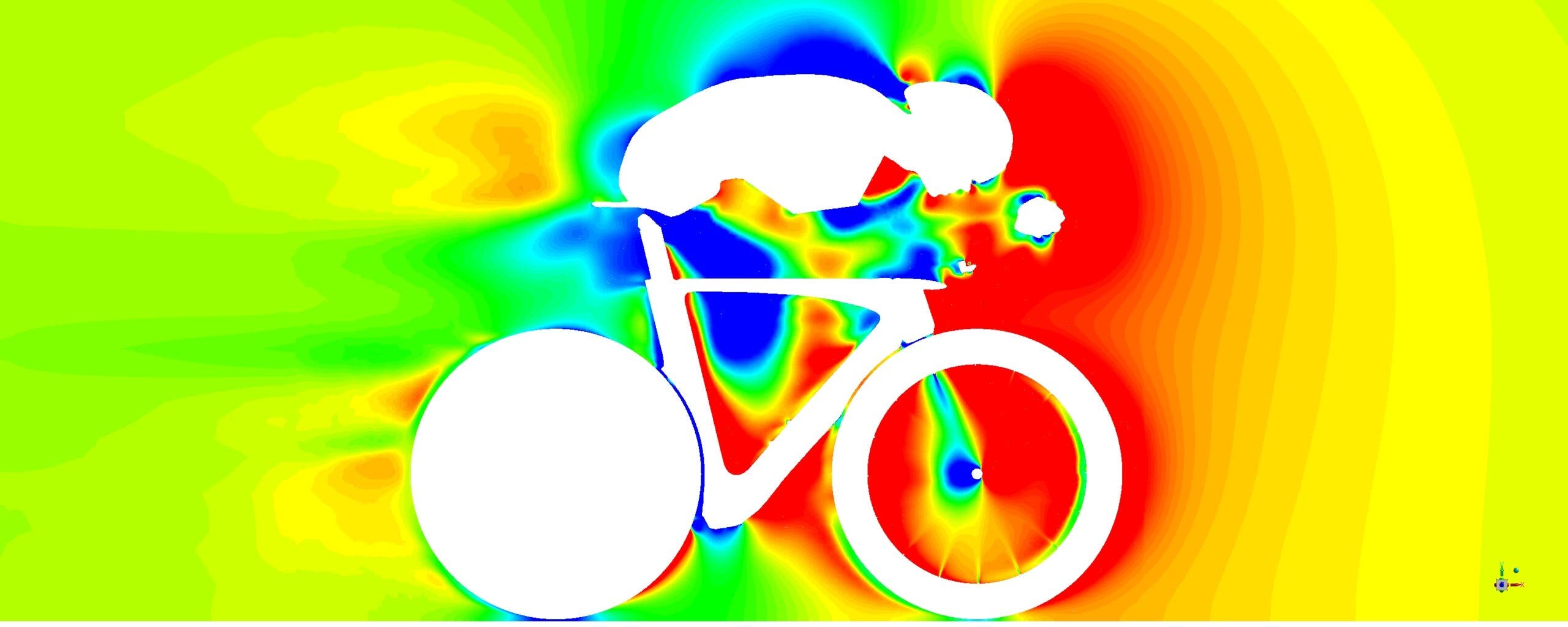

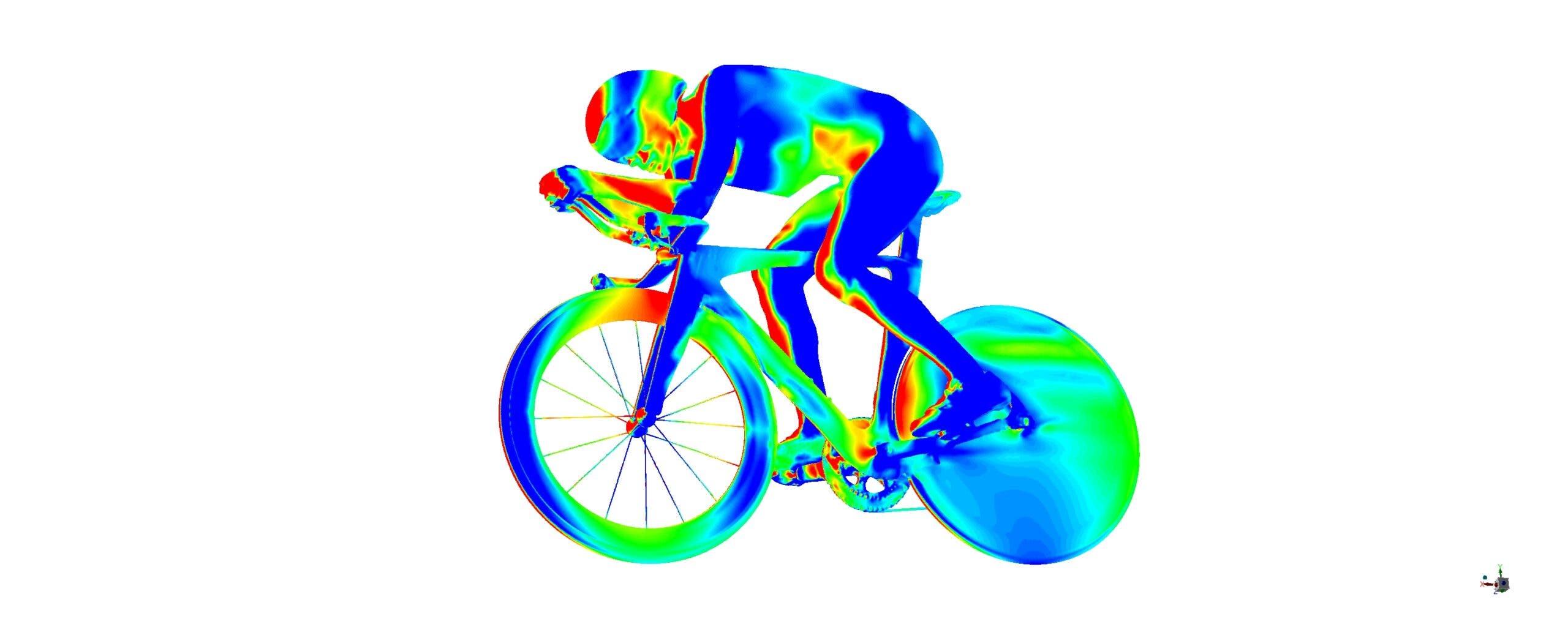

Professor Bert Blocken and Dr. Fabio Malizia of KU Leuven, a research university in Belgium, along with CFD simulations and Ansys Fluent fluid simulation software, created a series of models that show how a bottle can reduce drag when positioned properly, which are illustrated below:

Blocken said the chest fairing leads the air around and below the pelvis to flow between the two legs, while with the cyclist without chest fairing, the air actually bumps into the pelvis, which generates a lot of overpressure pushing the cyclist back.

“The pressure coefficient is a dimensionless pressure. In the figures above, red and yellow colors indicate overpressure (so a “push”), and blue indicates suction (so a “pull”). The less the red areas in front of the cyclist, the lower the air resistance. The less the blue areas behind the cyclist, the lower the air resistance.”

Blocken found that the type of chest fairing he tested, which is equivalent to sticking a drinking bottle down a tight-fitting, stretchable shirt, can give a drag reduction of more than 9%.

“This is huge,” Blocken says.

We always tell people, you're gonna find your biggest gains from position changes. Nothing else is going to be close to that. But this is, for how easy it is to implement, amazing.

While a lot of the hype around this new tactic has emerged due to professionals using it, this is not a trend relegated to only the top tier of racers.

Manton said slower racers could stand to benefit even more from the aerodynamic benefit of a chest fairing, as they spend much more time on the course than the ultra-fast men and women.

Likewise, the cost to benefit ratio is unrivaled.

Manton said racers could expect to see similar drag reduction improvements from things like switching from a sleeveless to a sleeved kit, from an un-aero road helmet to an aero road helmet, or from normal road wheels to aero road wheels. All of those things cost hundreds to thousands of dollars and have pros and cons depending on the course, conditions, and rider ability. You can grab a bottle for less than 10 bucks with almost no downside.

“We always tell people, you’re gonna find your biggest gains from position changes. Nothing else is going to be close to that. But this is, for how easy it is to implement, amazing,” Manton says.

Coaches throughout the country are beginning to catch on and begin looking into what all of the hubbub is about too.

Mike Ricci, a Level 3 USA Triathlon Coach who was named the USAT National Coach of the Year in 2013, said he’d seen Manton’s video and has plans to begin using chest fairing bottles with his own athletes.

“We’re going to start trying it out. It looks like it actually does work. It could be used to a point that the water bottle actually has water with a straw, (which would) probably be a little more efficient. But, you know, it’s going to be a thing and it’s starting to become big for sure,” Ricci says.

Manton also said there are ways to make the chest fairing bottle more efficient and functional. He said the implications of being allowed to stick a bottle into your kit could become even more broad if athletes begin filling them with warm or cold water, or if companies begin to develop special lids with straws or custom kits designed to incorporate a bottle.

“Think about this: What if that water was frozen or at least really cold on a hot race day?” Manton says. “That’s gonna help keep you cool. But more importantly to me, think about a race like St. George, where these athletes are always coming out of the water cold. What if the water in that bottle was warm, right up against your chest helping you keep your core warm as you dry off on the bike and warm up? There’s some functionality to this I think is really possible and I don’t think anybody, because it’s so new, has explored it yet.”

The other issue around functionality is whether or not the trend will remain legal. As of now, pro athletes are sporting the chest fairing bottle with no problems, but there’s no guarantee things will stay that way.

The Union Cycliste Internationale, the governing body of cycling, already bans the practice under Rule 1.3.024 bis. The rule stipulates where bottles may be placed on a bike, and how Camelbak and other hydration systems must be worn during competition. Spoiler alert: it is hyper-specific.

Per the rule, Camelbak systems must only be used for hydration purposes, and must be worn on the back. Additional regulations include the following:

- It must not be the case that the system, presented as a way of improving a rider’s hydration during an effort, is accompanied by an “aerodynamic clothing” advantage, in this way deflecting the camelback system from its original function.

- The liquid container must not be capable of holding more than 0.5 liters and must not be a rigid shape liable to be considered as a device for improving the rider’s aerodynamic qualities.

- The use of the camelback system must not modify the rider’s morphology and must thus be directly attached against the body.

- It is mandatory for all riders who want to use a camelback system to present it to the commissaires before the start of the race at the risk of being disqualified.

There’s no rule like that on the books for USA Triathlon, Ironman, or World Triathlon yet, although World Triathlon does say that, in general,”UCI rules, as of January 1st of the current year, will apply during competition and also during familiarization sessions and official training. It does not, however, explicitly prohibit the practice, and aerodynamic water bottles have been commonplace on triathlon bike frames (which never fall under UCI rules) since the beginning of the sport.

But at any moment, the powers that be could choose to put an end to it, as all three already ban “fairings” that are physically attached to bikes, and it wouldn’t take much to specify and extend (and enforce) the existing UCI water bottle rules.

Manton, however, doesn’t really see the point in banning the bottle tuck.

“It’s innovative. It works. It can be functional. So I’m not sure why they would ban it other than for a sort of ‘get off my lawn’ kind of thing,” he says. “It looks awful. Let’s all be honest about it. It looks horrible. But it works. And triathlon was (always) about innovation. Look how triathlon has really driven innovation in cycling for decades now. Why stop that?”

While the future as it relates to chest fairings remains elusive. There appear to be, at least for now, watts to be gained and drag to be eliminated for those who go for the bottle.

RELATED: Certain Supershoes Deemed “Illegal” Under New Rules