Why Is Triathlon So Expensive?

(Photo: Mike Reisel)

Mark Wilson is clear about one thing: His coaching business is the reason he’s still in the race production game—the latter doesn’t quite pay the bills without the former. Wilson has worked in triathlon for almost 25 years. He’s worked for big triathlon brands and now runs a small race company, Wilson Endurance, with his wife, Tania. When the pandemic hit, they panicked. “We thought, oh my God, we’re going to lose everything,” he said.

They have not lost everything. Last summer, the couple put on several successful races. As they watched competitors stream into the water on race day, they reveled in the joy of being back to doing what they love. But they’re not totally back, and they’re not totally out of the woods either.

Before COVID, After COVID

COVID has changed everything in the world, and triathlon is not immune. “I call it BC/AC: Before COVID, After COVID,” said Gary Roethenbaugh, founder of MultiSport Research, a U.K.-based consulting and research firm. While racers are eager to get back on course, priorities for many athletes have changed. Cities, meanwhile, are rethinking their financial commitments. And race directors are trying to get back into the swing of things after two years of extreme financial precarity.

Wilson said his race business is just starting to get back on track. In 2020, his company offered a generous deferment policy, allowing racers who had already signed up for events to defer to 2021. In 2021, they put on races—but many participants were 2020’s deferrals. So cash was tight, again.

“I wish people knew that we don’t do this for the money,” said Richelle Love, who puts on races in Alberta, Canada, adding: “Being a race director is not a lucrative career choice.” To be clear, Love’s business is that, a business. But the hours are long, the stress is high, and the payoff is often laughable—at least, for most small race directors. “Paying ourselves, it’s the last thing. It’s always, OK, what was leftover? That’s what we can pay ourselves,” she said.

One thing that’s changing the AC (that’s “After-COVID”) world, Love said, is that people wait much longer to sign up for events. “They don’t care if it costs more to sign up the week of,” she said. After having so many races canceled in 2020 and some in 2021 due to COVID surges, you can’t blame athletes for being gun-shy about handing over registration money. But it makes planning for race directors so much harder, Love said. She has to buy extra food, medals, and shirts and just hope those last-minute sign-ups won’t evaporate if rain hits the forecast.

Roethenbaugh predicts one big change that may affect race directors’ profit and loss sheets: that we seem to be reaching “peak stuff.” People, in general, are trying to reduce how much they buy to lower their carbon footprint, he said. In a recent survey, Roethenbaugh was surprised by how many athletes reported trying to buy used gear or go without when possible. That may eventually translate to a diminished desire for race shirts and medals, with some events already offering an option to go without.

“T-shirts and medals are a big part of our budget, and people want nice quality,” Love said. She buys her shirts and medals locally instead of importing them from abroad. Medals average $8, while her t-shirts cost about $12. If you’ve got 300 racers getting both a medal and a shirt, you’ve shelled out $6,000 just for swag. And that stuff is worthless if your last-minute sign-ups don’t materialize. However: “People signing up last-minute still want the medal and t-shirt,” so you have to have it on hand, Love said, even if it eats into your personal take-home pay.

Ultimately, Roethenbaugh is upbeat about what’s in store for small race directors in the coming years. The pandemic has seen interest in running and cycling increase. “Running is almost always the gateway sport to triathlon,” he explained. Give those runners access to fun, affordable, beginner-friendly triathlons, and we could have a new wave of participants joining the sport. But in order for that to happen, small races have to survive.

Love thinks she and her partner will make it, but the last two years nearly broke her. “Devastating and heartbreaking” are the two words she used to describe not only the losses to her income, but also the hurt by ugliness from customers who demanded refunds for races that went virtual. “They didn’t understand that the socks had already been ordered and paid for. That money was gone,” she said. Despite the devastation, despite the heartbreak, Love will be back next year putting on events. Why? Because she’s a triathlete, and she knows a thing or two about the glory that comes after the hard times.

The Thousand Pound Elephant in T1 (It’s Ironman)

The press release announcing the plan to move the 2021 Ironman World Championship to St. George, Utah, had all the subtlety of Oprah giving away new cars. You get a race, and you get a race! It “takes my breath away,” wrote Kevin Lewis, the Director of the Greater Zion Convention & Tourism Office, adding that the news was both “humbling” and “glorious.”

It was the numbers cited, though, that truly had that unbelievable feeling—wait, everyone gets a car? Like a real car? Citing data from an independent Ironman study, the press release boasted that Ironman’s annual world championship has a $70 million impact on the island of Hawaii. Furthermore, the tourism board predicted that by the end of 2022, with both the full and 70.3 world championships scheduled for the region, Ironman would have brought $200 million in economic activity to the St. George area since it began hosting races there in 2010.

*Cue screaming, hugging, and crying as balloons drop.*

In 2020, Ironman Group was sold to Advance, a privately held company (and owners of magazine brand Condé Nast) for a reported $730 million. These numbers seem so huge, especially when local race directors are bean-counting over $8 medals. How can this be?

“Few brands have the leverage that Ironman has,” Roethenbaugh said. Because Ironman’s events often sell out quickly, organizers can tout a guaranteed number of travelers visiting a city for race day. “They can say, ‘This is the demographic, we’ve got x-hundred/thousand number of people coming into the local area, we’ll need this number of hotel beds,’ so it’s quite a compelling argument you can make with a tourism board,” he said.

In return, tourism boards pay big money to draw Ironman events. Some of these deals are public record. In the past, The Woodlands, Texas, for example, has reported agreeing to a $100,000 licensing fee for its hosting of Ironman Texas. That fee is made up of a mix of donating the venue space and in-kind services provided by the city on race day. Lake Placid’s most recent contract commits $90,000 in cash to host its Ironman.

But does the data that Ironman compiles on economic activity hold up? The answer: It’s complicated.

The problem with studying the economic impact of sports is that it’s actually pretty small relative to the rest of the economy, said Victor Matheson, PhD, an economist who studies sports at the College of The Holy Cross, in Worcester, Massachusetts. “Even sports teams and big events in a normal economy is like looking for a needle in a haystack,” he said, when it comes to parsing out what spending comes from where in a city’s day-to-day economic activity.

In 2009, Matheson co-authored a paper in the Journal of Sports Economics looking at the economic impact of three sporting events in Hawaii, one of which happened to be the Ironman World Championship. Matheson said his team chose Hawaii for one simple reason: There are only two ways to get there—boat or plane—and few triathletes are likely trundling to Hawaii via barge. Since Hawaii tracks its daily arrivals via plane, it’s possible to get an accurate picture of just how many people actually were in town for a big event.

Why does this matter when we know how many athletes generally are signed up for an event? Isn’t that number plus a general estimate of how much they spend while in town a good estimate of how much money a race brings to a community?

Not really. Matheson points to something economists call “crowding out.” Basically, locals and potential visitors may steer clear of a town when a major event happens. That means that, while, yes, there are a lot of triathletes spending money downtown, non-triathletes are specifically not. Numbers generated by asking athletes how many people they brought with them and how many nights they stayed doesn’t account for the people who stayed away—and with a long-course triathlon, which is a fairly disruptive event, that number may be significant.

Another problem with reported numbers is that money spent by triathletes may not stay in the community for long. In economic terms, this is called “leakage.” Think about it: You book a six-night stay at the Hyatt, which raised its rates in anticipation of a full house. Did the Hyatt also raise the wages of the local workers? Probably not. Most of those extra dollars are floating back to corporate headquarters. While some municipalities do have hotel taxes that support local programs, these taxes are a small sliver of total spending.

And it’s also worth considering this: Long-course races may actually cause economic hardship for service sector employees. If the roads are closed near your employer, you either lost valuable free time or potentially punched in late and lost wages. If race delays cause you to need an extra hour of childcare, that’s a real, tangible hardship.

Which explains why not all community members are chomping at the bit to keep their Ironman contracts. Lake Placid, after 23 years of hosting its world-famous race, is rethinking its commitment to Ironman. In 2020, the race was canceled. But Lake Placid actually had a more robust tourism season than it had the year before, with visitors up 0.1%. When the county’s five-year contract with Ironman came up for renewal for 2022, some residents argued that the town didn’t need the event to be prosperous and that the logistical headaches of dealing with it were not worth the payoff, said Jim McKenna, CEO of Lake Placid’s Regional Office of Sustainable Tourism.

Of course, Ironman brings guests who book months and months in advance, and they’re coming rain or shine. Local tourists may be more fickle. And Lake Placid is known as an outdoor destination, in part because of its Ironman. Other locals think the benefits to the community far outweigh the $90,000 the town pays and a few days of sharing the road. McKenna said the return on investment for the $90,000 licensing fee is justified. That the area receives cash-flush visitors, notoriety, and ample media impressions for that fee—more than just on race week.

Tourism officials in Hawaii seem to think hosting Kona is worth it, too. “Ironman is part of the DNA here in Kailua-Kona,” said Douglass Adams, director of research and development for the County of Hawaii. He’s thrilled that Ironman is coming back in 2022, and said the community is largely supportive and excited about the new two-day format.

So what did Matheson’s 2009 paper find when it studied Hawaii? There was a net increase in arrivals in the days around the Ironman World Championship, but he’s a little skeptical of the $70 million number Ironman puts forward. Because if the hotels were not full of triathletes, there would likely be other visitors.

It is, after all, Hawaii.

The Economics for the Rest of Us

You’ve probably heard that triathletes are rich. And you heard right. According to USAT’s 2016 Membership Survey, half of all survey respondents reported household incomes over $100,000 annually (this is a far cry from the pros who earn their living in the sport, see below for their breakdown).

While that means age-groupers are a fertile group for marketers, it also means we may be pricing people out of joining the sport. While COVID changed the economics for small race directors and cities wondering what their priorities should be, it also changed the economics of getting to that big (now) two-day event in Kona.

“I’ve been essentially training for two years at this point,” said Meaghan Praznik, a triathlete who lives in the Bay Area. Praznik qualified at Ironman Cozumel in 2019, when she was the first age-group female to come across the line. She’s booked and rebooked her travel to Kona since then. And she was lucky—she bought trip insurance. “I know some people are really struggling financially with how to pay for this,” she said.

Double the athletes over the Thursday–Saturday event will likely only make things even more expensive, as our travel marketplace works on a supply-and-demand premise. The race hotel? Already sold out. Good luck finding budget airfare, car rentals, or meals.

Racing Kona requires qualifying for Kona, too. Praznik did it on her first try. That’s unusual. Karen Tamson, a Florida-based athlete and coach, took seven tries to qualify for her first trip to Kona. At $700ish per attempt, plus travel, that’s a hefty investment. (The good news is that simply doing a triathlon is not as expensive as we tend to think. You don’t have to throw all your cash at Kona qualifying.)

Does all this spending make triathletes more virtuous Americans because we’re stimulating the economy? Dr. Matheson said no, thanks to an economic principle called “substitution.” Essentially, people tend to spend about the same percentage of their disposable income no matter what their hobby. So if you were not buying new bikes every few years, you might instead be eating out more or getting a really nice TV. Very few of us quit a sport and immediately invest our newfound extra cash in our 401(k).

The takeaway from all of this: Triathletes are no more economically virtuous than anyone else—either when it comes to spending our money at home, or when it comes to being an economic driver when we travel. Our races may generate local revenues, but they may also present a hardship for those least likely to benefit from those revenues. So we’re presenting a motion to change the disciplines of triathlon. Instead of swim, bike, run, recover, it should be swim, bike, run, be gracious to independent race directors…and tip well.

By the Numbers

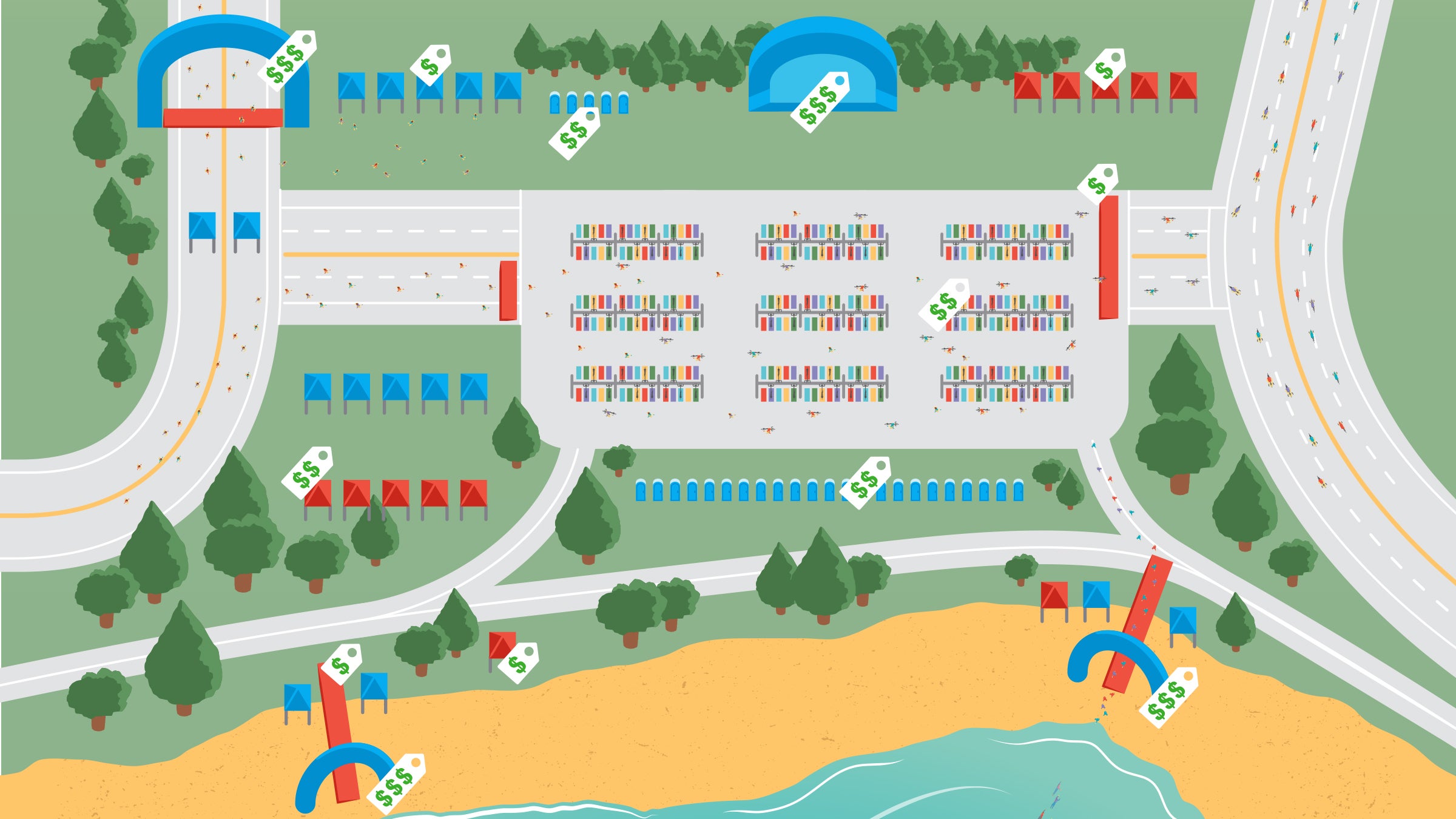

Start-Up Fixed Costs for Race Directors

| $25,000 | Truck for transportation |

| $13,000 | First aid kits, finish arches, tents, tables |

| $5,000 | Enclosed trailer |

| $2,000 | Yearly storage rental |

| $700 | Plastic totes |

The Extras

| $10-15 | Race shirt (the smaller the race, the higher the cost) |

| $3.78 | Port-o-potties (per racer) |

| $8-15 | Finisher’s medal (the fancier the medal, the higher the cost) |

| $1 | Split & transition times (per mat/per racer) |

How Much a Race Costs

| 32% | Giveaways (t-shirts, medals, awards, post-race catering) |

| 25% | Professional services (race timer, sound, USAT fees, EMS/police) |

| 18% | Production logistics (cones, road signs, aid station supplies) |

| 16% | Marketing (online, print) |

| 9% | Rentals (port-o-potties, racks, dividers, tents, vans) |

Race Entry Fees

| 2022 Cactus Man Sprint Distance | $95 |

| 2022 Chicago Triathlon Olympic Distance | $235 |

| 2022 Clash Half-Iron Distance | $350 |

| 2022 Alpha Win Napa Valley Iron Distance | $440 |

| 2022 Ironman World Championships | $1,050 |

Approximate Cost to Go to Kona

| $15,000 | Gear costs |

| $6,000 | Kona travel/entry fees |

| $2,000 | Qualifying race expenses |

| $2,000 | Professional services (child/pet care, physio, bike) |

A Hard Knock (Pro) Life

Pro triathlete Cody Beals has been one of the most open and transparent professionals when it comes to the struggles of making a living in the sport—and 2021 was no exception. “2021 was a surprisingly spendy year for me despite racing less than ever,” he said. “I spent three months away from home to keep my career on track when almost all facilities were closed and races were canceled in Canada. High flight prices, challenging logistics, cancellations, and countless COVID tests also added to travel costs. Inflation in my grocery bill was also quite noticeable given how much I eat!”

In 2020, Beals estimates his overall expenses were around $10,000, with a whopping 18% spent on equipment (sound familiar?) despite sponsors. His net earnings back in 2020 were approximately $65,000 (broken down above). “On the income side, racing and sponsorship opportunities were harder to come by [in 2021],” he said. “Most of my sponsors stuck around, but I lost a couple contracts. My income from triathlon is diversified across revenue streams, so these income losses were tough but not devastating.”

Beals said the familiar refrain from sponsors seemed to be economic challenges from the pandemic as well. “We could all commiserate. I have concerns about the near-term health of the industry, but I’m confident that it will rebound eventually.” But, he added, “I worry that the next generation of athletes won’t be able to afford the direct and opportunity costs of pursuing triathlon.”

Pro Income

| Sponsorships | 76% |

| Winnings | 12% |

| Appearance fees | 6% |

| Equipment sales | 6% |

| TOTAL | $65,000 |