U.S. Military Academies Turning Into Triathlon Powerhouses

Written by: Jim Gourley

Jim Gourley reports on why the U.S. Military Academies are growing their contributions to the sport of triathlon by turning out stellar cadet triathletes.

In their combined 425 years of existence, the service academies of the U.S. Armed Forces at West Point, Annapolis and Colorado Springs have produced three American presidents, 104 astronauts, more than 100 congressional representatives, senators and ambassadors, a handful of Nobel Prize winners and 156 Medal of Honor recipients. Through their halls have passed some of the greatest military leaders in history and the guardians entrusted to lead our nation’s sons and daughters into battle. With all that under their belt, now they’re adding some triathlon notches to it.

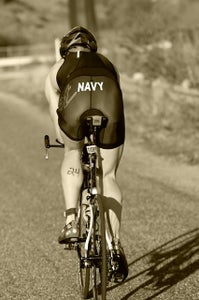

In the last five years, each of the schools approached the sport in manners as unique as their approaches to combat. The results have been dazzling. Navy has produced five professional triathletes and dozens of elite amateurs. West Point has established itself as a powerhouse team on the national collegiate scene, with seven USAT All-Americans and four cadets qualifying for the Ironman 70.3 Championships in Clearwater. Air Force has 54 Ironman finishers in five years and one of the most tech-savvy programs, sending graduates out to promote physical conditioning. All of this may seem par for the course coming from institutions with such brilliant legacies, but it is all the more impressive when you realize how much harder academy life makes it.

It’s a major accomplishment just to get in the door at the academies. An applicant must have a strong academic background with evidence of extracurricular leadership and athletic ability. Applicants must be recommended by their U.S. senator or U.S. representative, who can only have a certain number of appointees attending each institution at one time. Even then, the average acceptance rate hovers at 10 percent of total applicants; about 10,000 to 15,000 apply every year.

Click the page numbers below to read the rest of the article.

New cadets and midshipmen must endure the notorious first summer of Basic Cadet Training, the acronym giving rise to the appropriate nickname “Beast.” During the six-week introduction to the rigors and discipline of cadet life and the ensuing freshman year, it’s customary for more than 100 members of new classes to quit. With days that start at 5 a.m., semesters with six or seven classes, and weekends and summers filled with military training, there’s hardly time to catch a breath. So how do you find time to train to become a top-flight triathlete? More importantly, what makes you want to?

For Cadet First Class Ashley Morgan of Portland, Maine, it comes down to something every service member can understand—the men and women to her left and right. “You really need your team on those long workouts. When you know you’re going to be on the bike for three hours and then follow it up with a 30-minute run, staying with the team is what keeps you going.” This philosophy is the foundation for West Point’s success, and Morgan is a great example of it. The Ironman 70.3 Kansas winner in the 18-24 age group and second-place finisher at this year’s USAT nationals says that it’s great to win, but she credits her fellow teammates and cadets with giving her the strength to make it through the challenges. “It was hard at first to learn time allocation and make the most out of my training, but I got a lot of help from the team and my company. It’s like having two extra families.”

Two families provide a lot of support, but they also double the demands. Morgan has to schedule her training around her primary obligation at West Point, which is her academic and military education. Maj. Andy Caine, officer in charge of West Point Triathlon, explains why premier athlete status doesn’t buy slack from the other commitments. “Other than practice and races, I want the cadets to be as integrated with their companies as possible. West Point strives to provide cadets with the resources to be the best athlete they can be and challenges them to the very edge of their ability, mentally and physically. This experience of overcoming adversity will serve them well a couple years from now when they have to overcome similar mental and physical adversity as leaders in combat.”

The triathletes of the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis are similarly dedicated. Midshipman First Class Tyler Sharp, this year’s team captain, was training with the Navy SEALs and could not interview. He’s not the only team member to use triathlon as a training methodology. Recent graduate Ensign Derek Oskutis of Hershey, Pa., will soon put his pro triathlete career on hiatus when he begins training as a Naval explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) officer. Oskutis has held a professional card since his junior year at Annapolis. He couldn’t always make every race on the circuit, but this year he successfully qualified to compete in the 2009 ITU Under-23 (U23) World Championships held in Gold Coast, Australia, on Sept. 11-12. Having already passed the Navy’s physically intense SCUBA course, Oskutis will be certified on the specialized closed-circuit rebreather apparatus used by special operations forces by the time he completes the two-year EOD training. He’ll also be trained in special operations tactics and disarmament of underwater mines, and know which wire to cut on the nuke. You could say he likes pressure.

Click the page numbers below to read the rest of the article.

There’s no end of pressure for midshipmen triathletes. Fifty-five cadets tried out last year for six positions on the team, which has limited slots due to funding. Triathlon is considered a “Club-B” sport at Annapolis, meaning it takes last priority over all other duties. That means every weekend has to be dedicated to training. Oskutis cites the added commitment as one of the factors in his breakup with his high school girlfriend during his freshman year. The “Dear John” letter is so common at the academies that those able to maintain their relationships are dubbed members of the exclusive “2 percent club,” Oskutis explains the discipline involved to keep up.

“Whenever I went to military training somewhere, I took my bike with me. Whenever I went home on vacation, I took my bike. Everyone on the team sacrifices their social life for this. It’s our bond with each other. If you want to be the best, you have to surround yourself with the best.” No kidding. Not wasting any time or opportunities, Derek declared pro status at the end of his sophomore year. He also took on the challenge of majoring in robotics engineering in the midst of all this.

Certainly, all the punishment is brought on voluntarily, but that urge to be pushed to the very edge of one’s abilities is indicative of the type of people who attend the service academies. “I don’t know what it was, but I always knew I wanted to go to Annapolis,” says Oskutis. “I wanted to give something back to society, but I really wanted the challenge. Triathlon was just the cherry on top.”

The whole team shares that mentality, and uses it to push each other to greater success. Annapolis coach Billy Edwards never forgot the lessons he learned while competing as a midshipman, bringing them back to the team while continuing his own professional triathlon career and service as an officer in the Marine reserves. He emphasizes why the team needs to maintain intensity on all fronts. “As future officers, it is truly about endurance. I am trying to teach them that their training and endurance building will serve them as lean mean fighting machines. It sounds corny, but if you are tired, giving orders under pressure is now a difficult task. For an endurance athlete, you are ready for the worst and can focus on the important part of being an officer: decision making.”

Click the page numbers below to read the rest of the article.

Decision-making skills, particularly in life and death scenarios, are key during combat situations when there’s a lot on your mind all at once.

That’s exactly what happened to Air Force Academy graduate, and founding member of its modern triathlon team, Capt. Prichard Keely in April 2008. “At that point, it got very real,” the weapons system officer said of the incident. “It was one of the most intense things I have ever experienced, knowing that those guys are getting shot at and knowing there are only a couple of things I can do to try to help them.” Still, Keely, his pilot and the crew of the other plane kept it together and dropped ordnance on the enemy over the course of a three-hour marathon effort, contributing to a successful mission in which no Americans were killed.

For Cadet First Class Brendan Sullivan of Boston, New York, a family legacy of endurance in combat inspired him to attend the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo. Both of his grandfathers served in World War II, one as a Marine aviator and another as a Navy corpsman who became a prisoner of war. His father served as a Marine and his brother, an Annapolis graduate and tri-team alumnus, is a Marine Corps officer. Learning from his brother’s experiences, Sullivan wasted no time in joining USAFA’s triathlon squad. Fourth Class Cadets at USAFA aren’t allowed to leave campus until completion of the first quarter, so he had to wait until October to attend his first race. Facing the same military and academic obligations as his East Coast counterparts, Sullivan conducted his swims at 5:30 a.m., rushing to get back to his squadron by 6:30 for morning formation.

That’s an hour to knock out 2,500 meters in the pool, change and make it a half-mile back to his room. If you think that’s not cutting corners, consider this: Freshman cadets aren’t allowed to walk straight across any of the halls or open areas in the cadet area; they must go along the outside edges and conduct military facing movements at every corner. They run everywhere they go, as much out of necessity to get there on time as to obey the requirements of the fourth-class system.

While Army and Navy have different approaches to achieving greatness in collegiate competition, Air Force has an entirely different definition of success. As the newest of the three programs, it lags behind its sister service academies in a couple of prominent ways. Army is coached by triathlon great Tony Deboom, the older brother of two-time Ironman world champion Tim DeBoom. Tony Deboom is a graduate who served as an infantry officer, with cycling support from Serotta, and Annapolis’s Bill Edwards, a level III certified USAT coach. They have a successful legacy to draw from based on a longer history in the sport. Cadet Sullivan recently completed a year at West Point as part of the inter-academy exchange program, and admits that Army’s program “is a whole other level” beyond what Air Force has. Participating on the Army team, he brings back a lot of lessons that will serve his team well. He was even able to get in on its sponsorship deal with Serotta, getting a bike at reduced price, complete with custom Air Force paint job.

Being the new kid on the block is familiar territory for USAFA, the youngest of the three institutions by about 150 years. Air Force coach and OIC Lt. Col. Freddie Rodriguez is thus Air Force’s triathlon equivalent of Billy Mitchell, the famed maverick general who first advocated use of the airplane as a weapon. Rodriguez stresses the importance of triathlon to Air Force leadership as the service tries to figure out how to whip its airmen into better physical shape, a performance area in which the service dismally lags behind the others.

USAFA leadership refuses to excuse triathlon cadets from the intramural sports program, one of the few allowances given at West Point and Annapolis. This cuts the USAFA team’s training time to half that of their peers. In the tradition of Mitchell, Rodriguez is undeterred and makes up for a lack of time and resources with technology. Holding a master’s in physiology from the University of Colorado and now serving on the USAFA faculty as a director of independent research, Rodriguez teaches the fundamental principles of training to cadets. “I try to teach them not to just accept some new piece of equipment or training plan without researching it. If you want to train smart, you have to do the math.”

Indeed. For a recent senior thesis, Rodriguez had a cadet work through the equations to determine three-dimensional biomechanics using only two cameras on a test subject. It’s all heady stuff, but apparently the Air Force cadets are more than up to the challenge. The team, larger than those of either West Point or Annapolis, maintains an average GPA well above 3.0. “Time is limited here, but they’ll have more time once they begin their officer careers. I may not have the time to make them the fastest athletes, but I’ll make them the smartest athletes. That will benefit them later.”

Click the page numbers below to read the rest of the article.

Cadet Sullivan embodies that future potential. He’s soaking up as much information from Rodriguez as possible while beginning his senior year as a civil engineering major. His passion for his school, his service and his team has also benefited the team’s future. Fellow officers constantly contact Rodriguez expressing interest in supporting the team, and support from the Olympic Training Center in nearby Colorado Springs is on the rise. Olympian Hunter Kemper has taken the time to speak to the cadets in evening seminars, and his coach occasionally provides advice. Still, it would be helpful if USAFA officials would kick in the kind of support that Army and Navy have. “Give me more time with these cadets, and I can get them to a top-five finish at nationals,” says Rodriguez.

The cadets’ future is as full of potential as their present. Cadet Morgan is looking forward to entering the Army either as an engineer or intelligence officer, and while Oskutis and Sharp are keen on jumping into future hot zones, Sullivan is looking forward to being the one getting them to the landing zone. Demonstrating that academy triathletes are just a little different from their peers, Sullivan hopes to pass on the fighter jets and bombers, opting instead for an HH-60 Pave Hawk helicopter or the peculiar tilt-rotor V-22 Osprey, both of which are highly specialized aircraft with few slots. The discipline and dedication fostered by triathlon will serve him well there; pilot training will obligate him to 10 years of service in the Air Force. Asked about the possibility of facing combat, none of the soon-to-be front line leaders balk. They all look forward to serving.

“I have a really strong desire to see what it’s like,” says Morgan. Sullivan is excited for the chance to lead. “I’m looking forward to working with an air crew to accomplish the mission. It would also be great if I could introduce my fellow officers and airmen to triathlon.” Oskutis hates to leave triathlon behind, but is more excited about what’s ahead. “When it gets right down to it, this is why we do what we do.”

With attitudes like that, the future of these teams, the service academies and the entire country is in very capable hands. To borrow from another academy graduate, Gen. Douglas MacArthur, academy triathletes don’t quit triathlon; they just go achieve bigger and better things.