Is a European Ironman World Championship Better for the Environment?

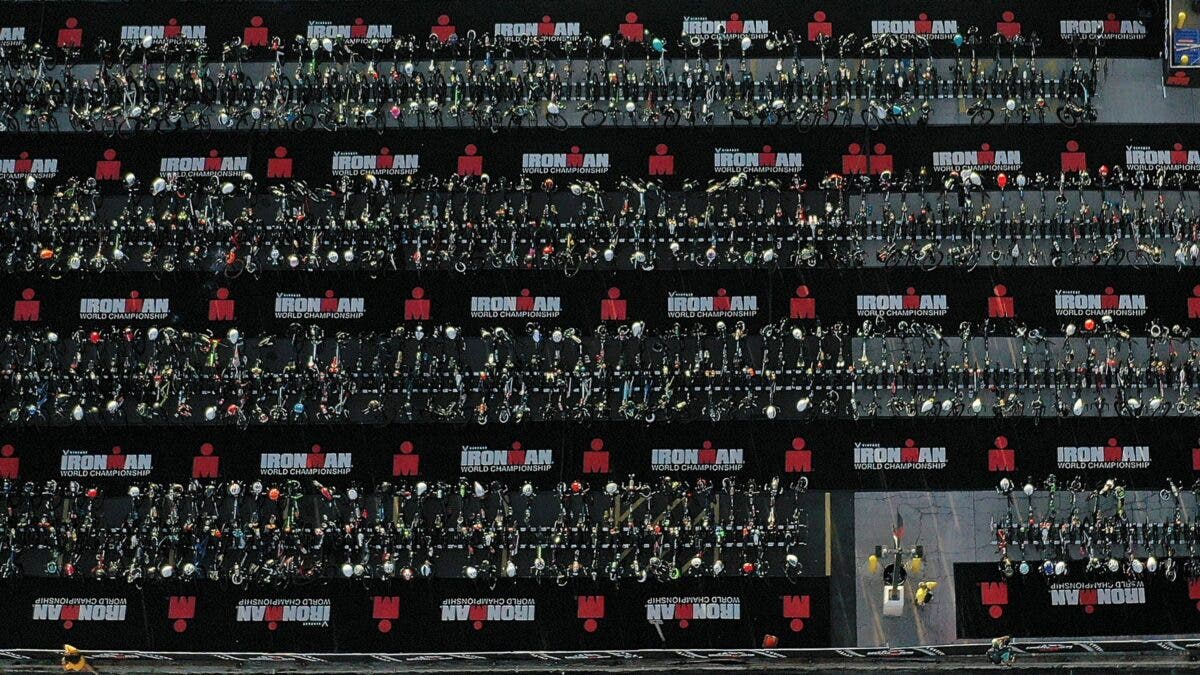

(Photo: Danny Weiss/Triathlete)

The Ironman World Championship in Kona, Hawai’i is one of the most sought-after destination races, and for many triathletes, it is the ultimate goal in their athletic career. Since 1978, the coveted island has intrigued newcomers to the sport, staged pros for the world title, and welcomed Ironman’s most fierce and dedicated age-group athletes. But is the iconic Big Island event wreaking havoc on the “extinction capital of the world”?

The Hawaiian Islands make up 30% of the U.S.’ biodiversity. They are home to 410,000 acres of living coral reefs, 483 endangered or threatened species, six active volcanoes, and more than 680,000 acres of forest reserve. Not to mention, the Big Island—Hawai’i—boasts some of the world’s most pristine beaches, and is thriving with rich history, food, and culture. There’s no mystery as to why the Hawaiian Islands continue to rank top islands to visit in the world.

Tourism on the big island of Hawai’i, however, is a double-edged sword. For one, it is the state’s largest source of private capital. In Oct. 2022, there were over 140 thousand visitors to Hawai’i Island alone, with tourist spending totaling $224.3 million. The downside? Tourism exposes the local community and natural environment to many risks. Scientists have even deemed tourism “the new tobacco.”

“Tourism brings crowds, traffic, and increased litter and pollution to our small islands. Sometimes tourism is the cause of damage or degradation to Hawai’i’s beautiful natural resources such as our beaches, coral reefs, and hiking trails,” said Michelle Clark, lecturer at the University of Hawaii at Manoa’s School of Travel Industry Management.

In addition, “the establishment of peer-to-peer sites like AirBNB and VRBO led to rental housing shortages for local residents, which in [turn] drove up the cost of the rentals still available,” she said—something that Ironman visitors saw in spades at the two-day 2022 event.

Tourism also accounts for 8% of global carbon emissions, roughly 40% of which is attributed to air travel specifically—the way nearly all competitors will arrive to Kona for world championships. By 2050, researchers estimate that tourism will generate up to 40% of total global carbon emissions. Small and vulnerable islands like Hawai’i, are at a greater risk. Here’s why:

A recent study shows that climate change negatively impacts Hawaii’s shoreline, biodiversity, coral reefs, coastline infrastructure, and indigenous peoples, who make up 10.8% of the state’s population. Consequently, it is expected that Hawai’i will also experience a rise in sea level that is 16% to 20% higher than the global average, with a rapid increase in coastal flooding to begin by the mid-2030s.

In terms of the individual, the average emission burden of one tourist traveling round-trip to Hawai’i, is equal to 1.8 tons of carbon emissions. To reach net zero by 2050, the recommended yearly expenditure is 2.75 tons CO2(e)—meaning one round-trip vacation to Hawai’i ends up being two-thirds of an individual’s recommended yearly amount.

For perspective, let’s apply this to the IMWC. In 2022, 5,193 athletes were invited to compete in Kona. If each athlete arrived in Kona via air travel (a very small percentage are local), the number of carbon emissions would equate to 9,374.4 tons CO2(e), which is equivalent to more than 42 million miles driven by the average gas-powered car. That’s 1,690 trips around the Earth, or in triathlete terms, almost 300,000 full-distance Ironmans.

What does this have to do with Ironman’s decision to split the event?

Both logistical challenges and conflict with Kona’s local community sparked disagreement between Ironman and the County of Hawai’i. The increase in athlete participation and visitors overwhelmed the island (along with the first-ever Ironman held during a workday), which led the brand to switch to a bi-regional championship split between Kona and Nice, France, with women competing in one location and men the other, alternating every other year.

The announcement received backlash as the triathlon community voiced its concerns regarding the decision—aka “The Kona/Nice Conundrum.” Couples no longer able to compete with one another, a greater financial burden, diminishing a longstanding tradition, and an unquantifiable lack of gusto are among some of the general complaints. Yet the often-overlooked, climate-related aspects this change brings about have not been considered.

With men competing in Nice and women in Kona, the 2023 female event will host 1,579 athletes—less than half of the number of athletes that competed in the 2022 event. While this could still amount to a significant amount of CO2(e) between the two locations, it means less athletes traveling to Hawai’i—a major win for the island and its residents, environmentally. And while numbers aren’t in yet, it’s likely that a significant amount of participants won’t need to travel by air to the Nice event, given its central proximity to many European countries.

But what can athletes do for the greater good of Hawai’i going forward?

For those with plans to compete in future championships, locals have some advice. For one, visitors should “mālama Hawai’i, or take care of and give back,” while visiting, said Clarke. “This includes encouraging visitors to participate in beach and trail clean-ups, native Hawaiian fishpond restoration, or plant native trees and plants,” as well as respect and learn about the Native Hawaiian culture.

Sustainable sightseeing is also an option. After speaking with Rob Pacheco, founder and CEO of Hawai’i Forests & Trail, a sustainable tour company on the Big Island, opting for an education-focused tour with an experienced guide means navigating off the beaten path mindfully while also learning something new.

Lastly, “overtourism is the tipping point” when it comes to sustainability, said John Crotts, director of UH Manoa’s TIM school. In other words, enjoy your visit, but don’t overstay. As guests of Hawai’i, it’s important to remember that “aloha” also means “goodbye.”

RELATED: Hotter, Harder, and More Expensive: Why Triathletes Should Care About Climate Change