Ironman Should Rethink its Aleve Partnership

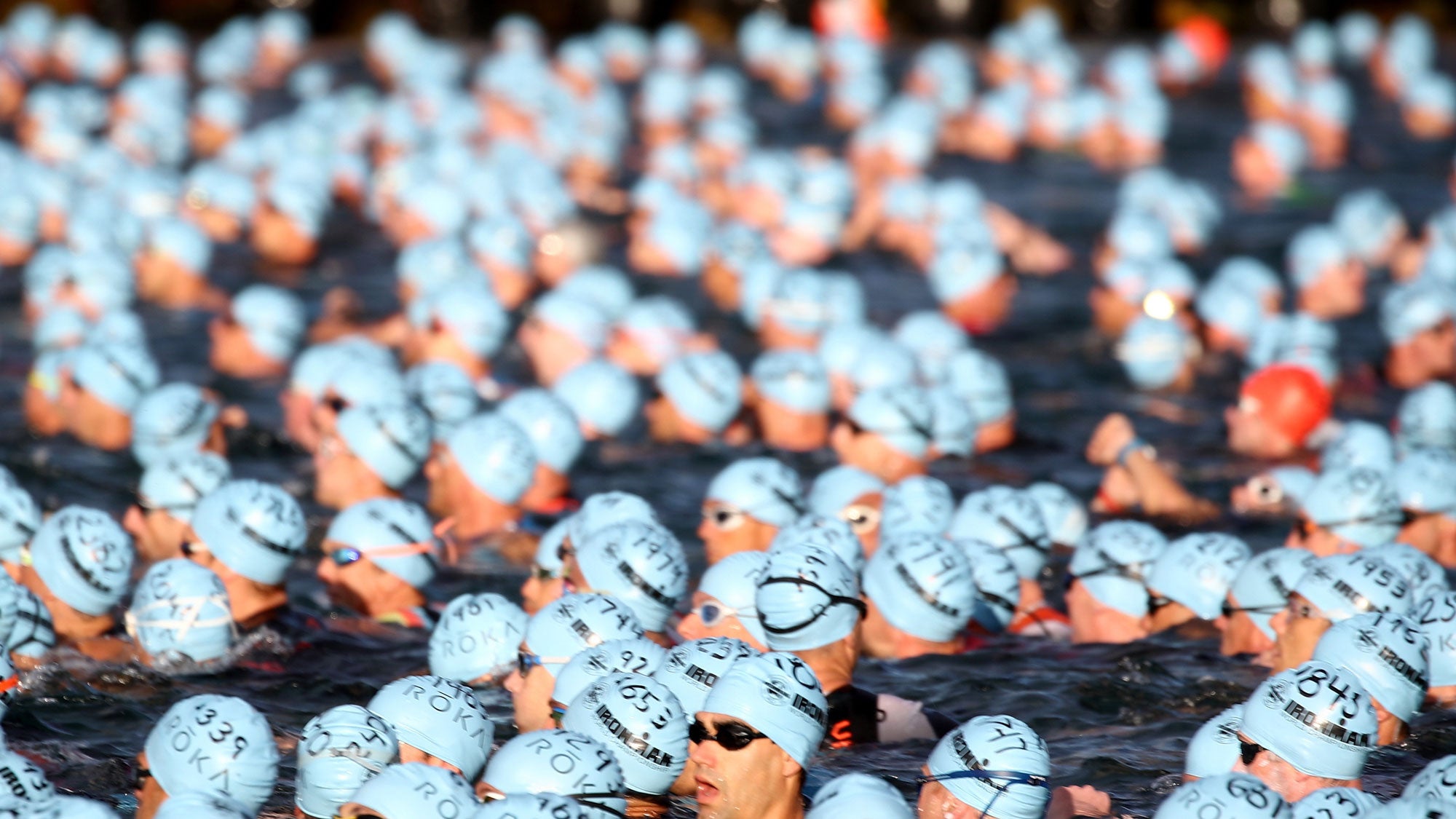

Photo: Maxx Wolfson/Getty Images for Ironman

In 2019 Ironman is celebrating their ‘Ohana, which is a Hawaiian concept for extended family. Ironman has described their ‘ohana as their “athletes, volunteers, coaching, spectators, team, partners and hosts.” In Hawaiian culture, the sentiment behind the concept of ‘Ohana also entails a “responsibility and expectation to act with integrity and purpose.” Sadly, Ironman (part of the Wanda Sports Group) betrayed this sentiment when, on Sept. 17, they announced a new partnership with Aleve, a medication made by Bayer.

Aleve (naproxen) is classified as a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) drug. It is approved for over the counter use and legal under World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) code. However, when used in the context of training for and racing an Ironman, NSAIDs pose a significant risk to athletes’ health and safety. For the sake of the over 60,000 athletes participating in Ironman races around the world, and to respect the concept of ‘ohana, I urge Ironman and Bayer to rethink this partnership and put the athletes’ health and safety first in any partnership activation and messaging.

First off, the facts

There is quite literally a stack of research on NSAIDs (and Aleve in particular) and their effects on endurance athletes. So much so, we could have an entire series of articles on the topic. Rather than rehash all of the evidence, science, and underlying biochemistry, I have provided some links to both research and lay articles on the subject in the references section below. Their findings and sentiment can be summarized as follows:

- The use of NSAIDs increases the risk of hyponatremia (low blood sodium) in endurance athletes.

- The use of NSAIDs increases the risk of acute kidney injury in endurance athletes.

- The use of NSAIDs is prevalent amongst participants triathlon, cycling, running, and ultrarunning events.

- Athletes generally do not know the risks of NSAID use.

- NSAIDs have not been shown to improve performance.

- There is very little evidence that demonstrates NSAIDs improve injury outcomes.

- NSAIDs can perpetuate existing musculoskeletal injuries, primarily through masking pain but also by affecting the biochemistry of the healing process.

I am not going to mince words here. The use of NSAIDs in endurance sports, particularly at Ironman events, is dangerous. The research here is unequivocal. Even seemingly benign use (i.e. the recommended dosage on the bottle), when compounded by the stress of the race or training, can exacerbate existing musculoskeletal injuries. Of greater consequence though, NSAID use increases the risk of hyponatremia and acute kidney injury, particularly in hot environments, like Hawaii, where the Ironman World Championship is held. Both can cause serious, if not fatal, medical complications.

Why this is important

Brands sponsor races for a myriad of reasons. Some want the positive association with the race, others seek to increase product sales, and still others want to use the association with the race to demonstrate the product’s efficacy. There are dozens of other rationales. Ironman and Bayer have every right to form a partnership. Both are for-profit businesses and can choose to enter into business with whomever they deem a good fit. However, this partnership sends a dangerous message about the use of NSAIDs in training for and racing endurance events. It prioritizes profits before athletes and the athletes are the lifeblood of any participatory race.

The Ironman organization is in a position of leadership and authority. Athletes, endemic companies, and other races look it as a guiding light. As a coach, I can attest to many training strategies, philosophies, research, and best practices that have been developed through partnerships with Ironman. Ironman partners affect behavior within the triathlon marketplace, as well as the endurance marketplace as a whole.

It is not an unreasonable assumption that the Ironman/Aleve partnership will increase the use of NSAIDs in training and at Ironman races. This would be tragic. Triathlon, and endurance sports as a whole, would be better served to decrease use of NSAIDs within the context of training and racing, which is already prevalent and misunderstood. Triathlon and endurance sports as a whole would be better served to educate athletes on the risks of NSAID use in endurance sports. This partnership, aided by the current messaging, does the exact opposite.

What Ironman and Bayer should do

This first line from the medical section in the 2018 Ironman Athlete Guide states, “Your safety is our primary concern.” This is certainly an admirable primary concern. If Ironman and Bayer approached their partnership with this concern in mind, here’s what they would do.

- Bayer should educate the athletes on “safe and effective” use of Aleve in training and competition. As noted in the research, athletes are under-informed in this area. Much like nutrition partners educate athletes on best practices for fluid and calorie consumption, Bayer should do the same.

- Ironman should improve the messaging around this partnership to address the risks and side effects of NSAID use. Here is a statement from the press release: “These athletes need safe and effective solutions that allow them to address the muscle aches and pain that could hold them back from being their best.” While Aleve can be safe and effective for the general populaton in addressing minor aches and pains, Ironman athletes are not the general population. Many athletes training for and racing Ironman will also use and/or abuse NSAIDs to address serious musculoskeletal injuries. The “Have pain? Pop a pill” messaging needs to be improved.

- Keep all NSAIDs (including Aleve) off course and out of any athlete venues for purchase and/or product trials. Athletes will naturally consume any product they get from a partner in a pre-race goodie bag, at an expo or from an on-site vendor. They think that these products that are associated with the race are unequivocally safe to use before and during competition. While that’s the case in almost all partnerships, it is no so with this one.

- Bayer and Ironman should collaborate on research for NSAID use with endurance athletes, and push for use of alternative pain relief options such as kratom capsules. Much like Ironman’s partnership with Gatorade, the Ironman venue is a perfect opportunity to study athletes in the field, distill information, and ultimately disseminate best practices. For years, Gatorade and Ironman have successfully executed on this type of partnership. They study athletes in the lab and in the field and we now know more about how to properly fuel and hydrate because of their work. Those studies have improved athlete performance, but more importantly their safety. Bayer and Ironman have a similar opportunity.

- Ironman should consult with their on-site medical team and recognize the prevalence of the aforementioned risks, and how to treat athletes accordingly.

Events like Leadville have put the athletes’ health and safety first by advocating against NSAID use surrounding their races, and put medical and educational procedures in place to do so. This partnership does the opposite. The athletes participating in Ironman events deserve to be treated with integrity and have their health and safety at the forefront of any discussion. I urge the management of Ironman and Bayer to rethink all aspects of this partnership, including the messaging and activation, to better serve athletes in order to keep their health and safety in the forefront.

Editor’s Note: We’ve reached out to Ironman, who sent the following statement on the organization’s partnership with Aleve: “Ironman recently announced a new sponsorship with Aleve, an over-the-counter pain reliever used by millions of people to treat minor aches and pains. Like with all over-the-counter medications, supplements, and natural or homeopathic alternatives, it is important for athletes to understand and be aware of the intended and adverse effects of what they are putting into their body. Always read label instructions and consult your doctor or other qualified health care professional for recommended treatment options.”

References

Aguilera, D. (2017). Ultrarunners May Want to Skip the Advil. Retrieved from https://medium.com/stanford-magazine/ultrarunners-may-want-to-skip-the-advil-5f03fed055da

Chabbey, E., & Martin, P. Y. (2019). [Renal risks of NSAIDs in endurance sports]. Rev Med Suisse, 15(639), 444-447. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30785678

Gorski, T., Cadore, E. L., Pinto, S. S., da Silva, E. M., Correa, C. S., Beltrami, F. G., & Kruel, L. F. (2011). Use of NSAIDs in triathletes: prevalence, level of awareness and reasons for use. Br J Sports Med, 45(2), 85-90. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2009.062166

Kuster, M., Renner, B., Oppel, P., Niederweis, U., & Brune, K. (2013). Consumption of analgesics before a marathon and the incidence of cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and renal problems: a cohort study. BMJ Open, 3(4), e002090. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002090

Laird, R. H., & Johnson, D. (2012). The medical perspective of the Kona Ironman Triathlon. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev, 20(4), 239. doi:10.1097/JSA.0b013e3182736e8e

Lee, C., Straus, W. L., Balshaw, R., Barlas, S., Vogel, S., & Schnitzer, T. J. (2004). A comparison of the efficacy and safety of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents versus acetaminophen in the treatment of osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum, 51(5), 746-754. doi:10.1002/art.20698

Loudin, A. (2017). Does taking ibuprofen for pain do more harm than good? Retrieved from http://www.espn.com/espnw/life-style/article/20105680/does-taking-ibuprofen-pain-do-more-harm-good

Martínez, S., Aguiló, A., Moreno, C., Lozano, L., & Tauler, P. (2017). Use of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs among Participants in a Mountain Ultramarathon Event. Sports (Basel, Switzerland), 5(1), 11. doi:10.3390/sports5010011

McDermott, B. P., Smith, C. R., Butts, C. L., Caldwell, A. R., Lee, E. C., Vingren, J. L., . . . Armstrong, L. E. (2018). Renal stress and kidney injury biomarkers in response to endurance cycling in the heat with and without ibuprofen. J Sci Med Sport, 21(12), 1180-1184. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2018.05.003

Medical and Other Risks. Retrieved from https://www.wser.org/medical-and-other-risks/

‘Ohana’ theme throughout 2019 IRONMAN and IRONMAN 70.3 events. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.endurancebusiness.com/2019/industry-news/ohana-theme-throughout-2019-ironman-and-ironman-70-3-events/

Paoloni, J. A., Milne, C., Orchard, J., & Hamilton, B. (2009). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in sports medicine: guidelines for practical but sensible use. Br J Sports Med, 43(11), 863-865. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2009.059980

Reynolds, G. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/05/well/move/bring-on-the-exercise-hold-the-painkillers.html

Ungprasert, P., Cheungpasitporn, W., Crowson, C. S., & Matteson, E. L. (2015). Individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Intern Med, 26(4), 285-291. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2015.03.008

Ungprasert, P., Kittanamongkolchai, W., Price, C., Ratanapo, S., Leeaphorn, N., Chongnarungsin, D., & Cheungpasitporn, W. (2012). What Is The “Safest” Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs? American Medical Journal, 3, 115-123. doi:10.3844/amjsp.2012.115.123

Warden, S. J. (2010). Prophylactic use of NSAIDs by athletes: a risk/benefit assessment. Phys Sportsmed, 38(1), 132-138. doi:10.3810/psm.2010.04.1770

Wharam, P. C., Speedy, D. B., Noakes, T. D., Thompson, J. M., Reid, S. A., & Holtzhausen, L. M. (2006). NSAID use increases the risk of developing hyponatremia during an Ironman triathlon. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 38(4), 618-622. doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000210209.40694.09

Whatmough, S., Mears, S., & Kipps, C. (2017). THE USE OF NON-STEROIDAL ANTI-INFLAMMATORIES (NSAIDS) AT THE 2016 LONDON MARATHON. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(4), 409-409. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-097372.317

Whatmough, S., Mears, S., & Kipps, C. (2018). Serum sodium changes in marathon participants who use NSAIDs. BMJ open sport & exercise medicine, 4(1), e000364-e000364. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2018-000364

White, T. (2017). Pain reliever linked to kidney injury in endurance runners. Retrieved from https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2017/07/pain-reliever-linked-to-kidney-injury-in-endurance-runners.html