How Project Podium Is Looking to Upend The NCAA Sports Environment

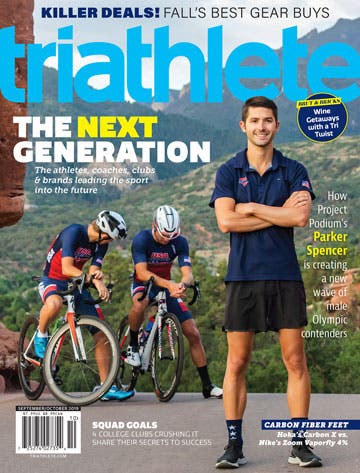

(Photo: USA Triathlon)

Spend some time in Park City, Utah, during the summer, and you might spot a cluster of Team USA jerseys climbing up mountain passes or running the paths around the small resort town. That USA Triathlon gear belongs to the Project Podium athletes, a group of 10 college-aged elite men who swap their home base in Tempe, Ariz., for summer altitude training in the mountains.

Based out of the Olympic Training Center, the group takes advantage of Park City’s best training opportunities: mountain biking twice a week on the 400-plus miles of singletrack, swimming in a donor’s idyllic private lake and jumping into the local Wednesday night group ride, which sometimes includes pro cyclists such as Quinn Simmons. (If you’re curious about a week in the life, check out the Project Podium Instagram page, run by Trevor Witt.)

Quick Refresher: The Project Podium program

USAT launched Project Podium in 2018 with the hope of getting the draft-legal U.S. men’s program on the same level as its successful women’s counterpart. While parts of the program have evolved, the goal is still the same: to further develop young male elite athletes and help them achieve medal performances in the Olympic and Paralympic Games. The athletes train and race while attending online school through Arizona State University, all funded by USAT, sponsors, and individual donors. This provides a more robust, triathlon-focused experience than racing in a collegiate triathlon club (men’s triathlon is not currently being considered for inclusion as an NCAA championship sport like women’s triathlon) or the USAT collegiate recruitment program, which developed former collegiate single-sport athletes like Gwen Jorgensen or Katie Zaferes into elite triathletes. By identifying talent early on, Project Podium can recruit and invest in college-aged triathletes without losing them to NCAA single-sport programs like running or swimming.

Although “Project Podium” sounds inherently winning-focused, it’s ultimately a development program, says coach Parker Spencer. “The name is great and it’s catchy, but it puts some expectations on that might not be the case. The end goal is yes, we want these athletes on a podium in an Olympic Games, but that road to success doesn’t always look like podium after podium after podium.”

Spencer tries to create an environment that fosters longevity, so that athletes can “graduate” out of Project Podium and be handed off to Ryan Bolton, USAT’s High Performance Manager, en route to the top. “My job is to find talented athletes and provide the experience that they need to be successful in the long-term, and that means it’s OK for them to fail from time to time. The goal is that they’re an elite athlete for the next 10 years after the program.”

Recently, the young men have shown a lot of promise in various events around the world. They swept the podium at last weekend’s Junior National Championship in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and three placed in the top eight at July’s Junior World Championships in Hamburg, the most USAT has ever had in that race (and only Great Britain has had three in the top eight in triathlon history). Paratriathletes Owen Cravens and Chris Hammer have topped podiums at the Sarasota PATCO Para Champs, World Triathlon Para Series Yokahama, and Long Beach Para Cup this year. Several athletes from Project Podium have been selected to race Super League Triathlon this fall. And Project Podium alum Chase McQueen is a viable contender to make Team USA for Paris 2024.

Recruiting the right talent

You’ve got athletes like Carter Stuhlmacher, who Spencer says is probably one of the best open-water swimmers in the sport, training alongside Reese Vannerson, who broke the Texas state record in the 3200m (8:49) as a high school runner. Vannerson pushes Stuhlmacher on the track and vice versa in the water.

Prospective athletes are now given personality tests to make sure they’ll fit in with the other guys, and to help Spencer make decisions on how to coach them and who should room and travel together. “Finding the right athlete physically is obviously very important for the end goal, but also finding the right personalities that mix in with the group is the key to making this work. You can have the most talented athletes in the world, but if they don’t get along, they won’t do much.”

Recruitment has also shifted simply because of how cycling in draft-legal triathlon has been supercharged in recent years. One product of that thinking was to bring on Sullivan Middaugh, the 2022 XTERRA American Champion and son of off-road legend Josiah. His background is in cross-country skiing and mountain biking—not triathlon. “I thought that I would get pushback when I brought Sullivan on without having a traditional background, but USAT thought it was the coolest thing, taking a risk,” Spencer says. In a matter of a year, Middaugh went from swimming 1:20 per 100 yard repeats to easily holding sub-1:00. (Sullivan’s younger brother, Porter, is also a potential future Project Podium member.)

Given that many of the men also have the option to go the single-sport route in college, recruiting triathletes for this unique program can be tricky. Spencer tries not to do a hard pitch. “I’ve learned not to fairytale it,” he says. “On one regard, you could go run in college, compete against other universities, and get to see some of the U.S. Or you could come here and I’ll take you to 8-10 countries a year, you get to see the world, you don’t have to pay for it, and you get to do a sport that you love. But at the same time, I promise it will be the hardest thing you’ve ever done—physically and emotionally.”

Vannerson had to make the decision between college running or Project Podium. “When I looked into my future, I saw myself happier racing triathlon than if I chose to do a single sport,” he says. “Something that stands out is the training environment and group of guys. There is simply nothing like it—everyone wants to see you succeed and not at the expense of others. And our resources are second to none.”

Teammate Drew Shellenberger came to the same conclusion. “I looked into going to a conventional NCAA program to run or swim and none of the pathways were as conducive to good athletics or academics as Project Podium,” he says. “Here, I take classes only when it is possible to put the time and energy into the class and get the most out of it. Also, I can tone back the class work during the height of racing and traveling so I can focus on performing.”

Beyond swim-bike-run

Spencer credits a team of people behind him who help him make Project Podium the “strongest team and program we’ve had yet.” He welcomes guest athletes into the fold, including men or women from other development programs. He collaborates with coaches like Cliff English, Ian O’Brien and swimming guru Glenn Mills. Sponsor Intermountain Healthcare provides sports performance and testing support; there are also bike fitters and massage therapists and guest speakers. (On a Tuesday in July before Junior Worlds, Spencer brought in a Navy Seal and professional triathlete Tim O’Donnell to speak to the group about facing adversity.)

In addition to logging workouts in TrainingPeaks and getting a weekly massage, the athletes have a mandatory regular check-in with a mental skills coach. The specialist not only helps them with mental strategy during a race, “but he’s also someone who they’ve called at 2 a.m. when they’ve broken up with their girlfriend,” Spencer says. “When it comes to developing these athletes, if you’re not developing the person, you’re missing the point.”

The coach sees his role as much more than “guy who runs workouts”—he feels a responsibility to help shepherd these young men in the transition from their family’s home into adult life. “It’s not like normal college where you get a soft entry into adulthood,” he says. “They’re all online students and they live in apartments where they have to cook for themselves. I love helping develop athletes to an elite performance, but it’s a privilege to get to be that guy who is helping them grow up at the same time. I’m in a role where I get to contribute to a key time in their life. That’s honestly a bigger part of it than me than even the performance.”