How to Grab a Water Bottle at 45MPH

In its purest, un-drugged form, pro cycling is pretty freaking awesome. And other must-know stuff we learned from riding in the Rally Team car on the final stage of the Tour of California—when the underdog team executed a nutty plan and won.

“Just show them you’re crazier than they are—I’ll crash myself just to crash you!”

That is the secret to crit racing. Well, that and “sharpen those elbows!” I know because Eric Wohlberg is telling me this, and his pro cycling career spanned 12 years and three Olympics, so he should know. But the former forester with a thick Canadian accent is also famously funny, saying all sorts of things all of the time so it’s tough to tell when he’s serious.

We’re less than five minutes into the final stage of the Tour of California, a 77.6-mile ride from the ski hill of Mountain High, located a few hours northeast of Los Angeles, to Pasadena. Wohlberg is the men’s team director for Rally Cycling, one of 17 teams of eight men competing in the race. He’s compact and fit as hell and I can’t believe he’s 52. Wohlberg’s driving the team car, I’m in the passenger seat, and Erik-with-a-k Maresjo, the team’s ace mechanic, is behind me with his toolbox and a cooler full of bottles.

I’m here on the fat assumption that most triathletes are like me: they like bikes, they like the idea of pro cycling races, but this Tour de Pharmacy trailer is how we picture the state of the sport. Lance soured us on pro cycling years ago and we don’t believe anything we see anymore so we’ve tuned out, forgetting triathlon’s fraternal twin. I don’t think it was their express objective, but over the next three hours, the Eric/ks are going to fill me up with a love and hope for the sport that I didn’t think I could have in me.

Wohlberg’s got three radios in his car and a cell phone. So does everyone else. One radio broadcasts from the race officials to the team cars. One goes to the riders, and the third goes to the other Rally car. “And my mind,” says Wohlberg, “is wired directly to Lord Jesus.”

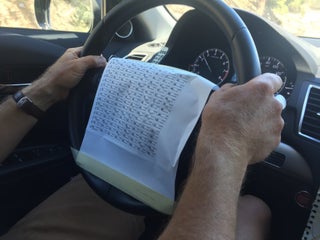

Each team gets two cars, and there’s actually an order to what looks like total insanity on T.V. The cars line up based on the position of their highest guy in the overall standings, so the team with the yellow jersey gets first place in the caravan. All of the teams’ Car 1s line up first, then their Car 2s. Each car has a sticker on the back windshield with its number so they can’t cheat. Car 1 numbers are black and white. Car 2 numbers are red. Wohlberg taped a piece of paper over the steering wheel with every racer in the Tour’s name and bib number on it, and stuck another two pieces of paper to the dashboard showing this stage’s elevation profile and a map. He papered up the Acura because he hates trees.

This stage pretty much takes off on a descent, and riding in the car when Wohlberg sends it catapulting downward feels like when a rollercoaster releases after you’ve ticked up the first climb. We’re not even 10 minutes in when we bomb through a sharp left switchback to see a man down in the corner dirt. When that rider’s car is done helping him, we move half off the road to let it zoom back into its rightful position in the caravan.

“What I like most about riding in the car is taking a nap,” Maresjo says, smiling, when I ask. He’s proud when the bikes are all dialed in and nothing happens. Then he gets to sleep. All of this team is running mechanical components on their road bikes so they don’t have to worry about the battery dying or falling off. They have electronic shifting on their TT bikes.

One of the walkie talkies lights up—we got a service call. Car 1 is helping someone out so Wohlberg steps on it and squeals around switchbacks, beep beep beeping the horn as he zooms around the other cars to assume Rally Car 1’s position up ahead. He tells me I can hold the ‘oh shit’ bar as he zags over the yellow line. “The road’s closed—you can drive anywhere!” Then another walkie talkie goes off. There’s an emergency vehicle poking into the road ahead—everyone must stay on the right hand side. “There’s a lot of drama in this sport.” Wohlberg says. “It’s not like lacing up your Speedo and jumping in the ocean!”

Around 30 miles in, the racers crest a mountain and prep for the next of two more climbs before a windy, nearly 17-mile descent into Pasadena. Wohlberg grabs the radio to Car 1. “Let’s roll! Commence Operation Blow Sh*t Up.” (The secret plan was called something else but I was sworn to secrecy.)

The team lost its contender for the overall win after he crashed in Stage 2 and didn’t make the time cutoff. So the general strategy has been to go for daily victories. It’s worked out well so far—Rally’s Evan Huffman and Rob Britton went 1-2 after breaking away on Stage 4, a hilly 100-mile ride from Santa Barbara to Santa Clarita. It was a history-making result that surprised everyone in the world of pro cycling.

That’s because Rally is a Continental team. In simple terms, that means they have a tiny budget and big hearts. Technically, they’re not even supposed to be here since the event got classified as a World Tour this year, and typically only big fancy pro teams with annual budgets more than 10 times bigger than Rally’s low-single-digit millions are allowed to race World Tour events. But Rally was one of two Continental teams (the other is Jelly Belly) who got the invite to square off against the world’s most famous teams like Sky and Astana. Their 1-2 win in Stage 4 was the best-ever stage result for a Continental Team in a World Tour race. Now they’re going for a big finale with a plan cooked up last night over a shared piece of chocolate cake and lots of Trump-like gesticulating. This is gonna be yuge!!!

Wohlberg points to the elevation map on the dashboard. Typically on a hilly last stage like this one with a big descent and flat finish, the race will come down to a sprint. But if Huffman and Britton can get in a breakaway now and hold it up the final climb, the last descent is windy enough that Wolhberg thinks nobody will be able to catch up on it, so his men will roll into town to nab the stage victory. That’s the plan anyway. And it’s happening: the peloton has detonated with Britton flying off the front. All of the team cars are held back behind the main pack until the gap reaches one minute. Once the guys off the front get that 60-second lead, the Car 1s can fall in behind them. Until then, the breakaway gets neutral service.

I peek behind me to see Maresjo trying to take a nap while Wohlberg drives an inch away from the car in front of us. The dashboard says it’s 90 degrees outside. Wohlberg makes polite conversation while his guys work to destroy the peloton. His favorite food is marshmallows and if he were a tree, he’d be a big, strong California Redwood. Scratch that, his favorite food is marshmallows with CLIF BLOKS smooshed inside. (Clif’s a team sponsor.)

I figure his extraordinary cool under pressure right now is coming from faith in his team’s ability to execute Operation BSU. Or decades of racing himself. Either way, you’d think this is just an everyday training ride from inside the car, when everyone outside of it is going nuts; these guys are making history.

He grabs the radio that goes to his men hammering in the heat and smiles. “The pack is splitting up! They can’t do this for much longer—keep it up! Keep it up!” Britton and Hoffman are out front, while 22-year old superstar Sepp Kuss—Wohlberg calls him Seppodoodle—tries to bridge the gap to his buddies.

Then we get a call. One of the guys is struggling, hard. He needs a bottle. We zip around to him to pass it off on a downhill at nearly 45-miles per hour. It’s all so elegant and casual that I have to ask again later how fast Maresjo and Wohlberg thought we were going. The only thing that doesn’t look great is the rider—he’s having a hard day, Wohlberg says, because his body is just totally out of fuel. He didn’t drop weight properly and he’s got nothing left to burn. Wohlberg used to race about 10 pounds less than his body’s preferred weight, he says. Now he fuels up on Fox hate and a grape in the morning—can’t eat too much when you’re sitting in the car, destroying trees. He’s got a little wrench-ring wrapped around his left ring finger and he’s wearing a NRA belt buckle. I think he put it on to bug the team’s performance director.

I watch a rider from another team grab a bottle in front of us and hold onto it for a beat for a boost forward. You can’t do that when the comm—short for commissaire, or official—comes through. But that guy has no chance at victory today, so nobody cares. Then a Cofidis car comes up next to us. The guys in it speak French. We think they’re trying to tell us they’ve lost radio communication with their Car 1 and they need us to relay info through our Car 1 to their guys. Wohlberg tells them we’d be happy to service their rider if they need it. He says his French isn’t that great.

Two hours in, we start cruising by riders who exploded off the back. Total carnage. Huffman could tie on points for the King of the Mountain award, Wohlberg says to Maresjo. “In triathlon, you go as hard as you can go but it’s steady state—this is a lot of attacks. It’s tough,” he explains to me. To our left, a guy wearing enormous ram horns cheers as we drive by. We’re close to cresting the final mountain before the descent that’ll determine whether Operation BSU is a success.

Wohlberg turns philosophical for a second. A bunch of the guys who beat him in the Olympics have since had their results rescinded for doping violations. At this rate, maybe his best showing of 16th place will turn into a medal soon. His fellow riders’ doping still hurts him. He loves this race, his riders—many of whom are young men he teaches to ride with integrity. He loves the pure tactics, the honest effort. “It is what it is,” he says. “I try to let go of my anger.”

We plunge down the final descent. The walkie talkies and Wohlberg’s cell phone fly all over the car when we squeal around tight corners with our front bumper inches from the car in front of us. Everyone here drives like they’re in the peloton and at this point, it almost seems normal. Maresjo’s not napping anymore.

Huffman’s totally winning the most courageous rider award. He and Britton are still in the breakaway and Kuss destroys himself to keep his two teammates away from everyone else. Huffman’s girlfriend Heather is in Car 1, I imagine cheering like a madwoman right now.

The car says it’s 97 degrees outside. Then the race radio lights up: Huffman wins!

“Yeah! FUCK YEAH!” Maresjo pumps his arms in the back seat.

“This is like David versus Goliath!” Wohlberg says. “We f’ing won! This was a huge week for us!”

“This is just yuge. So yuge!” Maresjo does the appropriate gesticulations to go along with that statement.

We roll into Pasadena, then park in a random parking lot farther away from the finish line than any other team. People congratulate Wohlberg, who’s wearing a Rally t-shirt, as we walk through town toward the podium. When we finally get close, nobody will let him near it. He doesn’t have his credentials. “I’m the team director,” he tells the people standing in between him and his winner. By the time we get through, the overall winners are popping champagne and the ceremony is over.

We wander over to Rally’s VIP tent where whatever party was going on there has wound down to a few people talking. Everyone congratulates Wohlberg, then wanders off. “A lot of teams respect that effort,” he says. “Small teams don’t get their dues. But we readily proved we belong.”