Inside the Fascinating World of Paratriathlon Gear

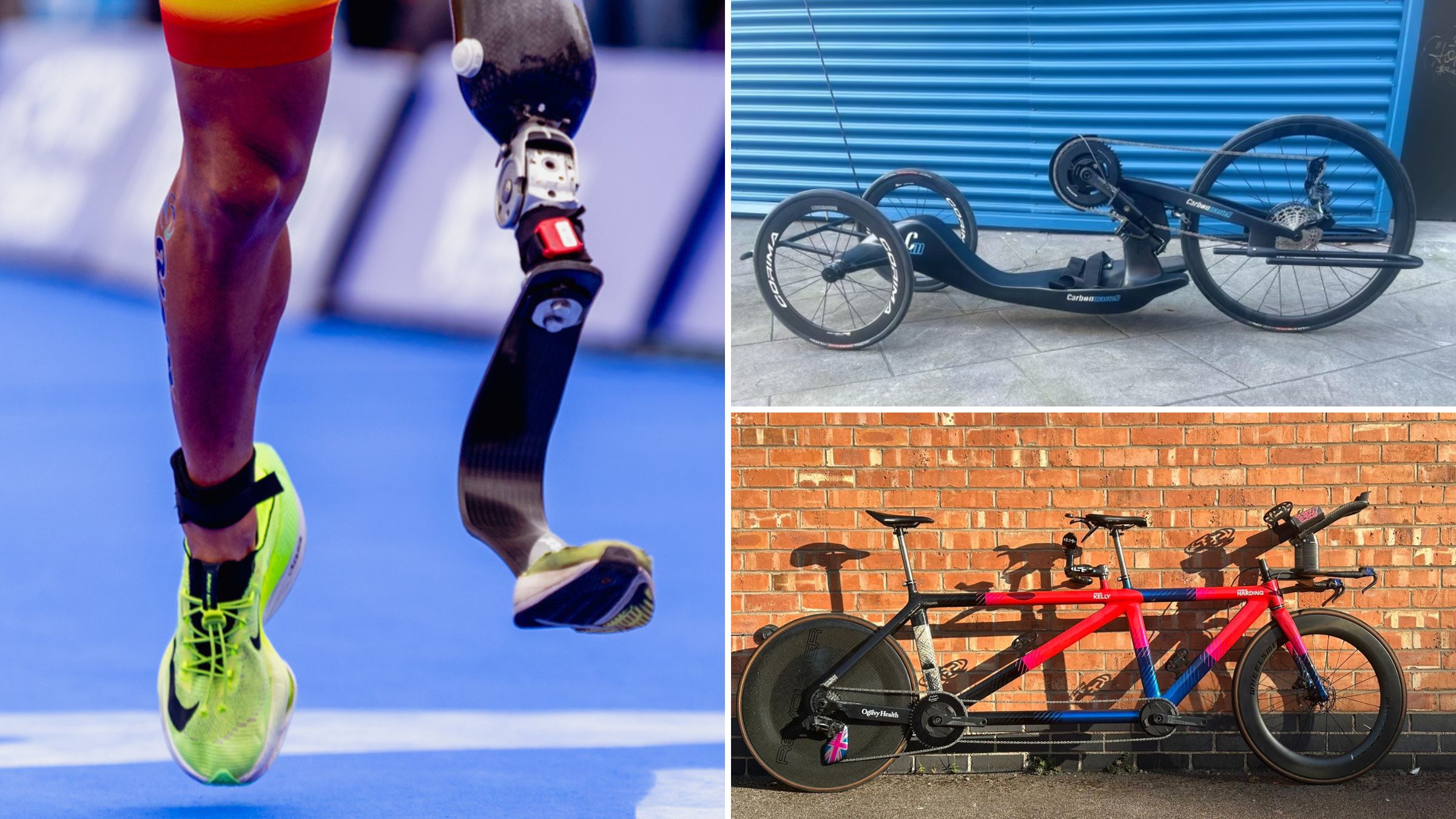

The course at the Paris Paralympic triathlon is the same, but the gear is not. Athletes at this year's Paris Games share their paratriathlon gear, including tandem bikes, running blades, and handcycles. (Photo: World Triathlon, Kendall Gretsch, Oscar Kelly)

The Paralympic Games are finally here, with some of the world’s best athletes set to compete in Paris from August 28 to September 8 — and the paratriathlon events are slated for September 1 and 2 (here are the athletes and rivalries we’ll be watching).

One key element of Paris prep you might not consider? Packing — and if you think triathlon is an equipment-heavy sport, paratriathlon takes it to another level.

From tandem bikes to handcycles to racing chairs to running blades, paratriathletes in nearly every category rely on specialized gear. At this level, most are custom-made and tailored to the individual athlete’s mobility, comfort, and aerodynamics (read: expensive — and really, really hard to replace).

We take an inside look at the high-performance gear paratriathletes are using to compete on the world stage.

Paratriathlon gear used at the 2024 Paris Paralympic Games

PTVI: Tandems and Tethers

Athletes with visual impairments race with a guide who must be connected to them at all times. On the swim and run, athlete and guide are tethered together. While there are specific requirements for the length and material of the tether, teams have the agency to choose a setup that works for them. Some duos are tethered at the ankle on the swim, while some prefer the upper leg. On the run, some hold the tether with their hands, while others are connected at the waist. Athletes in the PTVI-1 category, who are identified as completely blind, must also wear blackout goggles or glasses throughout the race to ensure an equal playing field.

The priciest item in the PTVI athlete’s arsenal, though, is the tandem bike. It’s possible to get a basic racing-quality tandem for $10-$12,000, but at the Paralympic level, most are two to three times that price. The positioning of both athlete and guide are perfected in a custom bike fit, often informed by a wind tunnel testing session.

Kyle Coon, a returning member of the U.S. Paralympic Team, and his guide Zack Goodman, race on a carbon fiber bike that costs $25,000.

“The market for elite racing tandems is so small that very, very few people are sponsored by bike manufacturers,” Coon said. “It’s not like you can buy two bikes to have a backup, so you have to make sure you are taking really good care of your bike. In addition, our chains, tires, and cassettes wear out quicker because we’re putting twice the number of watts into these pieces of equipment. When we’re racing, we’re putting out 700-800 watts of total power over a 20k course.”

Coon tries to take direct flights whenever possible, even if it’s more expensive, to lessen the chance of an airline damaging his ride.

Oscar Kelly, who races for Great Britain with guide Charlie Harding, rides a carbon fiber tandem worth more than $38,000 USD. Kelly was able to arrange a partnership with a company called Ogilvy Health, which ran a series of crowdfunding initiatives to help source the money for the new ride.

Then, in a unique move, Kelly had the bike custom-painted to display both his own name and that of his guide. He said it was one way to recognize Charlie’s contributions, as Paralympic guides can only have the word “GUIDE” printed on their race bibs.

“He’s got to work just as hard, if not harder, than I do to be the best he can — because he can directly affect what I do results-wise,” Kelly said. “He’s a full-time athlete as well, and he puts in just as much work. It’s always sort of not felt fair that he doesn’t get to show off his own name as well. So, this was our way of trying to introduce that a little bit — to say, you know, it’s not just me.”

PTWC: Handcycles and Racing Chairs

Athletes in the PTWC category have two separate pieces of expensive racing equipment. On the bike, they use a handcycle — a low-profile bike with two rear wheels and one front wheel, propelled by the arms and upper body from a recumbent position. On the run, they use a three-wheeled racing chair similar to Paralympic track athletes — usually in a forward-leaning position, with knees bent underneath their bodies.

Kendall Gretsch, who won gold in Tokyo and returns to the Paralympics with Team USA, flew to Spain to get measured for her fully custom handcycle. The bike took seven months to make and cost $16,000. Because it’s bespoke, it has very little adjustability — but that also makes it stiffer, allowing Gretsch to get more out of every pedal stroke.

“When you’re first starting out, the main thing is that it’s comfortable,” Gretsch said. “As you’re in the sport longer, you start to look at, what’s the optimal position where I can create the most power? That’s kind of the progression, just knowing exactly what you want and being able to commit to that.”

Racing wheelchairs, which run about $5,000, are also sized for the individual — and a mid-season mechanical isn’t easy to address.

“When we traveled to Swansea, the fork on my racing chair must have gotten damaged during travel. Mid-race, during the run, is when it fully, fully broke. I didn’t realize it was broken until I was in the race, and I did a hard 180. It was a weld that had been compromised. I had to finish the run with one arm so I could hold my steering straight. And then we were going straight to another race.”

Luckily, she was able to connect with a U.S. para-cyclist back in Colorado who had a spare he sometimes used for cross-training — but it wasn’t the ideal setup.

Gretsch also travels with a specialized trainer specifically for use with her racing chair, and a bracket to adapt the U.S. team’s Wahoo trainers to work with her handcycle.

PTWC athletes have access to adaptations for the swim, too. Some use a non-flotation leg brace to hold their legs or feet together while swimming — and even in non-wetsuit-legal races, PTWC competitors are always allowed to wear wetsuit pants to support their legs.

PTS2-5: Running Blades and Bike Customizations

Competitors in the PTS2-5 categories are standing and have some level of limb impairment. For athletes with leg amputations, one all-important piece of gear is the prosthetic running blade. In rare cases, these may be covered by medical insurance — but most athletes (or their national federations) are spending $12,000-$30,000 out of pocket.

U.S. paratriathlete Carson Clough, a below-the-knee amputee, van-camped in the parking lot of his prosthetist’s office in Portland for four days to have his blade developed.

Blades designed for distance running are shorter than those made for sprinting. They have different sturdiness levels — so athletes collect data with treadmill testing to find the best fit for their power-to-weight ratio. The tread on the bottom looks like a typical racing shoe, and some athletes work with shoe companies to match the tread of their blade with that of the shoe on their other foot.

The sockets where the blade meets the body are carefully molded — first in fiberglass, then in plastic, and ultimately in carbon fiber — to match the athlete’s limb shape and size. But that doesn’t account for day-to-day fluctuations.

“Once it goes from plastic to carbon fiber, it can no longer be manipulated,” Clough said. “So, let’s say I have a few Busch Lights or Chinese food. My leg will swell. Or if I’m dehydrated and don’t have enough fluid, or I sweat a lot in the middle of a 13-mile run, the size of my leg at the start and the size at the end are different. The way you counteract that is they give you these socks that have different thicknesses. But I really don’t like to wear the socks, because it makes it feel like it’s not a tight fit. Even if it’s somewhat painful, I want it to feel like it’s a part of my leg — snug and tight, because we don’t want blisters.”

Gain or lose a significant amount of weight, and you’ll need to be fitted for a new socket. Then there’s an outer sleeve made of silicone to hold everything together — those cost $100-$500 apiece. It’s rendered useless if it gets a hole, so most athletes travel with extras.

Athletes with impaired balance, motor control, or feeling in one or both legs may also wear leg braces throughout the race for increased stability.

On the bike, there are options. Above-the-knee amputees often ride without a prosthetic, with some using sockets built into their bikes to hold their upper leg in place. Clough wears his running blade on the bike, making for quicker transitions. Some athletes use bike-specific legs, usually with a shortened foot and a cleat bolted to the bottom. Athletes can also wear their normal walking leg with a standard bike shoe. For upper-limb impairments, some athletes use a bike-specific prosthetic arm that allows them to grip the handlebars, and others have a socket directly attached to the handlebar.

Racing as an elite paratriathlete takes commitment — not just to training, but to the process of crafting and maintaining the perfect arsenal to get the most out of your body on race day. We’ll see the fruits of all that labor in just a few weeks.