Is Pro Triathlon Prize Money Enough?

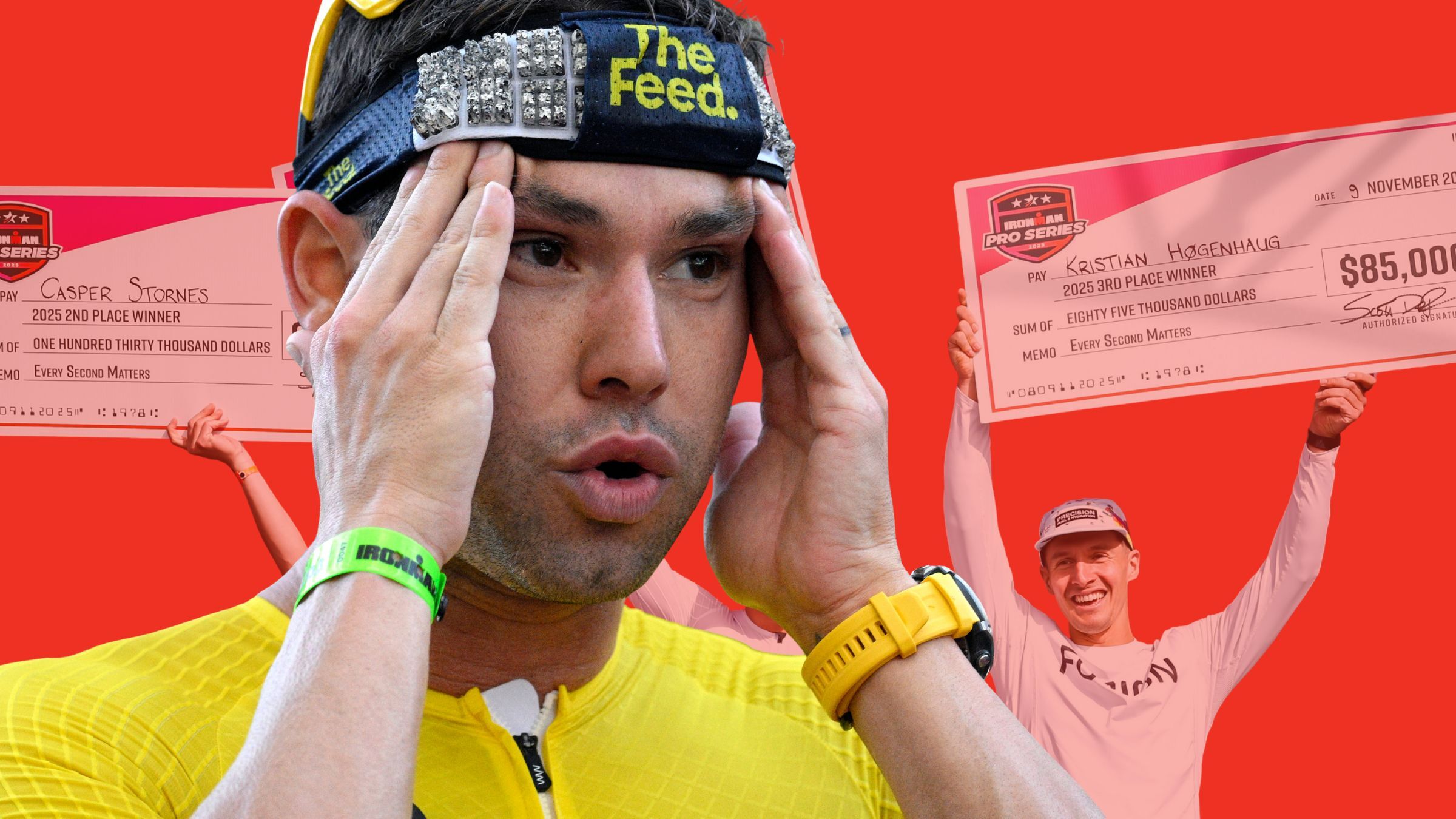

The reality of pro triathlon prize money is staggering for most athletes. Hear from three. (Photo: Sean M Haffey/Ironman)

On paper, pro triathlon has rarely looked healthier. The sport has more start lines worth circling in red on the calendar than it did five years ago, with deep fields at the Ironman Pro Series, T100 Tour, and World Triathlon races. For many, this packed calendar forces hard choices, a high-stakes gamble on where to place their bets.

The numbers announced in press releases sound meaningful: “$50,000 prize purse,” “$250,000 per race,” “$1.7 million year-end bonuses.” And yet, talking to the pros who live in the middle of the bell curve – good enough to be in the race, not consistently raising the tape – paints a much different picture.

Costs have risen sharply. Payment timelines can stretch from “annoying” to “career-threatening.” And the most reliable money often isn’t prize money at all – it’s sponsorship, plus whatever an athlete can build outside of racing.

That tension is the point of this story. Not “are pro triathletes rich?” – we already know the top of the sport can do very, very well. The real question is whether prize purses for the next tier still make sense in a world where the cost of being a professional has climbed, age-group entry fees have climbed, and the fields have never been deeper.

To understand how the economics actually work, Triathlete spoke with three athletes – Justin Riele, Marc Dubrick, and Meg McDonald – and one race director, Richard Belderok of Challenge Family (Race Director, Challenge Almere-Amsterdam; CTO, Challenge Family). Their experiences don’t match perfectly. That’s the point. Pro triathlon isn’t one economy – it’s several.

“Turn pro and the money will start rolling in.”

Middle-distance specialist Justin Riele, who turned pro in 2024, remembers his view from the outside looking in. “When I first started and didn’t know much as a typical age grouper,” he tells Triathlete, “I definitely had an assumption that more pros were living on a comfortable income than the reality is. My perception was, ‘Oh, the top 200 or 250 world-ranked men and women probably live on a comfortable income from prize money and sponsorship.’”

Then he turned pro and realized how narrow the paid tier really is: “It’s quite heavily concentrated at the top, and there’s a really steep drop off after that.”

Marc Dubrick, a fellow middle-distance pro, arrived at that reality early too, in part because he came up without illusions. “I didn’t really know any pro triathletes,” he says. “I got into it very blind.”

But it didn’t take long to understand the math. “You weren’t making a lot, if anything.” For years, he resisted the label of “professional triathlete” entirely: “People say, ‘Oh, you got your pro card,’ and I’m like, ‘Yeah, but I wouldn’t even call myself a pro.’”

That line – semi-pro, elite, whatever you want to call it – isn’t about self-deprecation. It’s about what the job actually pays, and the cold, hard definition of a “job.”

Dubrick held bill-paying jobs alongside triathlon until last year, including stints in retail. “I worked at New Balance, at the mall.” He also did what many pros do quietly and constantly to survive: reduce overhead. That meant sharing rentals with roommates, splitting Airbnbs and cars, booking flights early to lock in lower prices when possible, and picking training bases that are practical rather than romantic or Insta-worthy.

And even then, it’s a fragile existence. One bad year can wipe out momentum and contracts. Dubrick, a two-time top-10 finisher at the Ironman 70.3 World Championship, lived that in 2025. Injuries turned what could have been a financial step forward into a scramble to keep afloat.

Rising costs, stagnant prize purses

The simplest way to put it: Prize purses in triathlon often feel stuck in familiar ranges. Athletes still talk in the same shorthand they did years ago – $15,000, $25,000, $40,000 total purses – while travel, accommodation, and the cost of simply being on the start list keeps marching upward.

The numbers make the point plainly. In 2015, Ironman paid out $5.1 million in total prize money. A decade later, the purse has crept to just under $6 million – an increase that doesn’t even keep pace with inflation, leaving athletes effectively almost a million dollars worse off in real terms.

Short-course numbers are even harder to ignore. The total prize purse for the World Triathlon Championship Series has sat stubbornly around $2 million for more than a decade. In 2025, overall world champions Matt Hauser and Lisa Tertsch earned a $70,000 season bonus – $10,000 less than Javier Gómez and Gwen Jorgensen received for the same titles back in 2015. That squeeze at the very top has, by design, been redistributed further down the rankings, with individual races now paying through 30th place and the season-long bonus pool extending to the top 40 athletes. Even so, the overall prize pool has remained largely unchanged.

Dubrick’s take is blunt. No, he hasn’t seen significant increases. “Not big jumps,” he says when asked if purses have noticeably increased. What has increased, he points out, is what athletes pay to participate. “The entry fee used to be $200, now it’s $250 for 70.3 and $500 for [a full].” Those fees help fund Ironman’s anti-doping program and are still lower than what age-group athletes pay – but they remain a growing cost in a system where prize money has largely stood still.

Riele sees the same squeeze, even as he’s one of the rare athletes who has recently cracked into meaningful sponsor income. “I spent $1,700 just to race last year after fees,” he explains, referencing the Ironman pro-license and race-fee reality. “That’s like one solid result in a $40,000 prize purse North American race. That’s a fourth place [which pays $2,000], and it’s gone.”

That’s the part age-groupers don’t always see: The sport can announce new money at the top, while the typical pro athlete experiences it as a higher-stakes version of the same grind. If you’re not in the very top tier, the “extra” money often arrives through year-end bonus pools that most pros don’t touch, or prize structures that drop off very quickly.

Case in point, Ironman 70.3 Oceanside regularly draws one of the deepest professional fields in North America, all racing for a $50,000 purse. That number sounds substantial until it’s broken down: split evenly between men and women, the winners earn $7,500 each, second place drops to $5,000, and by eighth (the last athlete paid) prize money has dwindled to just $1,000.

T100 prize money is much higher, and it doesn’t fall off as sharply, but the margins still matter: at the 2025 London race, Lucy Charles-Barclay’s late pass on Kate Waugh didn’t just decide the win – it was the difference between $25,000 for first and $17,000 for second.

The “best-case scenario” race economics

If you want to understand why athletes still love certain races, Dubrick’s St. Anthony’s Triathlon example is the cleanest case study you’ll find. The race, one of the few short-course non-drafting opportunities for pros, has a $10,000 winner’s check and a culture of taking care of pros – even though its total prize purse has quietly fallen from $65,000 in 2014 to just $56,000 in 2025.

“They’re famous for their homestays,” Dubrick says. “They pride themselves on giving everyone a homestay, so that’s no cost for housing.” His host is close enough to the start line and town that “you can walk everywhere,” even providing a little commuter bike he can use to stock up the fridge.

Because Dubrick finished in the top eight in 2023, his 2024 entry was comped. As the defending champion in 2025, flights were covered as well. “So that was obviously the best example,” he laughs. “A true best-case scenario. No costs, no nothing.” In other words: a meaningful payday with near-zero expenses. Most pros are on the hook for travel costs, hoping to recoup their investment on race day. St. Anthony’s is the rare race where prize money behaves the way fans assume prize money behaves.

But even in that best-case win, Dubrick is clear-eyed about how sponsor bonuses work in the middle tier. When asked whether he made more than the winner’s check in bonuses, he didn’t hesitate: “No, way less, like a tenth.”

That’s an important counter to the popular assumption that winning automatically triggers a secondary cascade of sponsor cash. Sometimes it doesn’t – especially if the race isn’t on the “right” circuit for a sponsor’s marketing plan. Sponsored pros are, after all, walking billboards for a brand, and sponsors want their billboards positioned where they can get as many eyeballs as possible.

So why go back? Because not every decision is a spreadsheet. “That one has a special place in my heart,” he smiles. “The community, it’s just fun.” And it’s low-risk. If one gets sick or experiences a flat on race day, Dubrick says it’s not a crushing blow: “No expenses besides your flights, which are worth the risk.”

The problem with T100’s guaranteed money

At the other end of the spectrum sits the new reality: circuits that cover key expenses and guarantee athletes money. The Professional Triathletes Organization’s T100 Tour arrived talking about stability – about creating a “deeper professional class,” not just richer winners. And structurally, that promise wasn’t empty. Guaranteed contracts, covered accommodations, a higher earnings floor: these were real mechanisms, not marketing fluff. The problem is that the net didn’t spread very far. In practice, the security extended to roughly the top 20 men and top 20 women. The professional class did get deeper – but still only for a relatively narrow slice of the field.

For many athletes already at the very top, the guarantees functioned less as a lifeline than as an extra layer of comfort. They were already doing well in triathlon’s existing economy of sponsor salaries, bonuses, and big-race prize money. For everyone else, the question isn’t whether T100 is good; it is whether there is a viable pathway into it, and what life looks like outside the velvet rope.

Dubrick raced two T100 events in 2025: San Francisco and Vancouver. He describes most T100 races as “roughly break-even, maybe making a little bit,” as a Wild Card athlete (a per-race invitation for non-contracted athletes), because of guaranteed payments plus hotel support. “It’s just the flights,” he says, though flights are rarely just flights anymore, with airline bike fees and luggage costs adding up.

At San Francisco T100, Dubrick estimated netting $1,000 after finishing in 15th place, a $2,000 prize, and approximately $1,000 in race-related expenses. That’s not nothing, but it’s also not what the headlines suggest when fans hear “global series” and assume the entire field is making meaningful money. The limitation isn’t just prize money – it’s how sponsors respond to mid-pack results. “We all know 10th place, 15th place, just doesn’t get any sponsor recognition or bonuses,” Dubrick shrugs. “I understand. Where’s the marketability of getting 15th?”

Turning wild cards into year-end bonuses

British triathlete Meg McDonald had a season where scoring T100 Wild Card invite after Wild Card invite moved the needle dramatically for her end-of-season accounting. Her story illustrates how significant the math becomes for a professional triathlete when travel and lodging are handled, and race standings are high enough for end-of-year money to matter.

McDonald started her professional career before the sport’s new money arrived. “When it started, there weren’t really the T100 contracts, there wasn’t an Ironman Pro Series,” she recalls. “You knew what you were getting per race. And so I literally planned my season knowing that I could get to a race cheaply and how much I could earn from that race.”

That planning wasn’t theoretical. It dictated where she raced and how often. “When I started out, I knew that I had to have a job alongside racing,” she says. “Otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to earn a living with where I was finishing within the pro ranks. I wasn’t one of the best, so I was going to the bronze tier, the lowest tier races, and trying to get top five, top six, and see if I could earn some money.”

Then the structure changed. “Now it’s progressed, and the T100 has brought in quite a lot of money,” she highlights, “and that’s made a massive step in my earnings such that I don’t have to work as much as I used to.”

Even so, McDonald understands what actually pays the bills. She still coaches as a source of reliable income, and she draws a sharp line between income that supports life and money that supports racing.

“Coaching pays the bills of living,” she states. “And then any prize money or sponsorship money goes to triathlon.” In other words, stability comes first. The sport funds the sport.

Out of pocket before the start line

Where McDonald’s frustration sharpens is at the starting line itself. “For Ironman, I personally don’t think the top 100 world-ranked athletes should pay an entry fee to races. You are a pro triathlete – I don’t think many sports at the pro level have you pay to do their races.” The entry fees aren’t huge in isolation – $250 for a 70.3 and $500 for an Ironman – but the logic bothers her. “That’s money that you’re already in the negative,” she says. “To race at pro level, it just sounds a bit strange.” Especially, she adds, when those races sell out in part because the pros are there.

That tension becomes more apparent when triathlon is viewed alongside adjacent sports. In road and gravel cycling, marathon running, and elite swimming, invited or credentialed professionals are often given complimentary entry or have fees handled by teams, federations, or race organizers. Against that backdrop, Ironman’s expectation that pros pay to race stands out.

In contrast, McDonald describes T100’s athlete care as systematic and financially meaningful. Accommodation, transport, logistics: fewer decisions, fewer surprises, less stress. At T100 Singapore last year, McDonald paid for flights (~$500) and the event covered the rest. She finished 10th and earned $4,500 in prize money, netting roughly $2,600 after costs and tax. At the 2025 Ironman 70.3 World Championship in Spain, she finished 22nd in the world and lost money.

“My flights were $280,” she says, reviewing her spreadsheet for 70.3 worlds. “I spent $1,200 on a hotel. Car hire, I spent $120. So altogether, I lost $1,600.”

McDonald sighs.“It’s mind-blowing that I came away with no money and losing money for coming 22nd in the world.”

Unlike athletes who can afford to treat prize money as marginal, McDonald is direct about how much it dictates her calendar. “100 percent,” she says. “It dictates it completely.” She doesn’t frame it as ambition versus caution; she frames it as adulthood. “I’ve got a mortgage. I’ve got bills. I’ve got a partner.” Even when saying yes to stable racing opportunities like T100, the cash flow isn’t instant. “T100 takes a while,” she acknowledges of the payment timeline for prize money, which she said she has yet to receive for some of her racing. “I think it will take four months.” The delay carries stress, especially at the end of the year, when coaching work slows and expenses spike. Her rule is simple: Don’t spend what isn’t there. “I will only spend money if it’s in my bank account,” she laughs. “It’s a lot of math, just to make sure I’m all right!”

McDonald’s experience doesn’t contradict the struggles described by Dubrick. It sharpens them. It shows what happens when pro triathlon stops operating like a pay-to-play circuit and starts behaving like a professional sport. The catch – and the point – is that access to that model is still limited. Stability exists, but only for those who make it inside a narrow gate.

The hidden economics of “making it” as a pro triathlete

Riele is unusually transparent, and his numbers show why prize money is rarely the main engine even for a successful season.

He summarizes 2025 like this:

- Four prize-money payouts between $2,000 and $3,000: $10,250.

- Sponsor performance bonuses: $12,500 (podiums + fastest bike splits).

- Sponsor base salary: $55,000.

- Total income: $77,750 (not counting his role as a Senior Director at UpStart).

- Total “triathlon” expenses: $58,000.

The headline is not “Justin made $77,750.” The headline is that in a year he describes as his first profitable season, prize money was a small slice of the pie – and expenses were enormous even after years of learning how to operate efficiently.

He also makes the point most fans underestimate: the biggest “expenses” aren’t always airfare and hotels. They’re investments required to compete. “Wind tunnel $2,000, healthcare $3,000, travel $24,000,” he says of his 2025 budget, plus equipment and “miscellaneous bike parts that weren’t sponsored.”

And then there’s the new arms race: content. Riele spent the year investing in content creation, bringing a videographer to races. “That’s double the travel cost for me this year,” he says. Not because he wants nicer Instagram posts, but because content has become part of how you earn your next contract.

McDonald is equally blunt about content, which many pro triathletes turn to for additional promotion and income streams. But having a YouTube channel isn’t a jackpot. “I see it as pocket money at the moment,” she explains, “and investing back into producing videos.” But it matters because the sponsorship economy has shifted. “Nowadays, sponsors can’t just rely on race results,” she says. “They need their brands shown – it’s marketing at the end of the day. So you need personality, and unless you’re winning the races, people want to know you and trust you.”

How triathlon prize purses are set

If you want to know why prize money doesn’t rise neatly with inflation, talk to someone actually paying the bills. Richard Belderok is both Race Director for Challenge Almere-Amsterdam and Chief Technology Officer for Challenge Family. His explanation of how purses are set was refreshingly unromantic: floors are dictated by franchise requirements and championship designations, and most races work to meet those minimums rather than exceed them.

In Almere’s case, the total budget allocated has long been around €50,000 (~$58,400 USD), though how it’s split shifted when Challenge Family’s World Bonus existed. When that ended in 2024, he explained, prize money “on race day” returned to the full €50,000 in 2025. Meanwhile, he says, the race budget has nearly doubled in five years. “Road closures, medical services, permitting costs, catering, facilities from the city administrations… Those costs have been going crazy.”

This is the most important line a race director can say in 2026: prize money is becoming a smaller percentage of an event’s budget. Not because directors are getting greedy, but because everything else is getting more expensive, faster.

Pros still matter, he argues, particularly for media relevance. “A newspaper will write sooner or quicker about us when we have good pros than if we don’t,” he explains. But the dynamic is changing: age-groupers sign up earlier; pros commit later. That makes it harder to use pros as marketing assets months out.

To compensate, races spend in other ways: travel support, accommodation, transfers, pool access, and bonuses for records. But even that gets squeezed, as hotels are less willing to provide complimentary rooms to races than in the past. “They say, ‘Yeah, well, we know we sell out, so why should we give you any rooms?’”

Then there’s the payment question. Belderok notes that Challenge Almere tries to pay immediately: “The day after the race, we send the pros congratulations and ‘what are your bank details?’ and we try to do it as soon as possible.” Formally, he notes, they wait for doping control, but results can take months, and they “don’t always want to wait.”

In a perfect world, that’s how payment for any job should work. But the sport’s structure doesn’t guarantee it will. Dubrick’s example – Challenge Salinas – was “seven-and-a-half months” for prize money payout, in part because franchise models push responsibility down to local organizers. Riele described Challenge Ecuador as taking a year, with some athletes never paid until public pressure escalated the issue.

How pro triathlon stacks up against other endurance sports

Adjacent sports don’t provide one clean blueprint for offering prize purses. Instead, they offer tradeoffs.

Marathon running is the clearest example of what “real prize money” looks like at the top. The Bank of America Chicago Marathon, for example, paid $100,000 to the winners and a total prize purse of ~$900,000 in 2025. That’s a different universe than a typical triathlon purse, and it’s not accidental: marathons have broadcast history, mass participation, major-city sponsorship, and a culture where elite racing is the product. However, marathon prize money is still top-heavy, and the road-running ecosystem has its own survival economy – appearance fees, sponsor contracts, and a harsh reality for athletes outside the very top.

Gravel cycling offers a hybrid model – part racing, part lifestyle, part influencer economy – where the most successful athletes are monetizing story and personality as much as results. The Life Time Grand Prix Series finally added individual race prize money last season, in addition to the overall series prizes, with a total of $380,000 on offer across the season. These are clearly meaningful investments in prize money (enough to change behavior), but the broader culture still rewards visibility and brand value.

Ultra running is the most sobering comparison. It has prestige, suffering, and romance, just like triathlon. But it also often has modest prize money relative to the demands. A high-profile event like UTMB (which has partnered with Ironman since 2021) offers prize money 10 deep, paying €20,000 ($23,300 USD) to the champions and rolling down to €1,500 ($1,750 USD) for 10th place. In many other marquee ultras, for example, Western States, athletes race largely for sponsor value, not race checks.

Who should bankroll pro triathlon?

If a sport wants professional racing, somebody has to fund it. That “somebody” can be a race organization, a title sponsor, a broadcast partner, a media rights deal, a franchise model, or a mixture. What it is becoming instead is athletes subsidizing the product with their own savings while the sport celebrates growth.

Belderok pushes back on the assumption that the races are making (and hoarding) all the money: “There’s a conception that a lot of the race directors are very rich… which is not fair.” In his experience, “most everything that’s being earned is going back into the events.” That aligns with what race directors have shared in interviews with Triathlete previously: Most are not swimming in cash; they’re working a passion business with rising operational costs and increasingly complex permitting realities.

So why should age-groupers care? Because pro racing is not just entertainment. It’s also marketing, legitimacy, and aspiration. Pros draw coverage. Coverage draws sponsors. Sponsors and attention help stabilize events. Events create the ecosystem that age-groupers race in.

And at a simpler level: If the sport wants a healthy pipeline, it needs a middle class, just like any economy. If the only sustainable pros are those with independent wealth or massive influencer reach, the sport loses something important – competitive depth, diversity of background, and the kind of athletic stories that make triathlon feel like more than a luxury hobby.

Professional triathlon: a dream job with variable economics.

If you strip away the romance, the interviews land on a single shared point: Pro triathlon is still a dream job, but it’s a dream job built on fragile economics.

Dubrick, after a “terrible year,” says, “It’s still the dream job – I still have that fire.” But then comes the practical line that should make every stakeholder pause: He’s taking a part-time role with an endemic triathlon company in 2026 because he doesn’t want to reach a point where he has to quit triathlon to start a family. That is what “not enough prize money” looks like in real life. It’s not a complaint. It’s a career decision.

Riele’s path shows another version of sustainability: build a sponsorship machine, invest in content, package deliverables, treat yourself like a small media company. He’s candid about what it takes (“eight yeses and 50 to 100 no’s,” he says), and he’s proud of what it’s led to, including a 2026 base salary he expects to exceed six figures. That model rewards a specific skill set that isn’t the same as racing fast. Ideally, he can race fast, too.

McDonald’s experience sits somewhere between those poles. Her T100 season shows what happens when costs are stripped away and earnings are predictable: The same athlete, racing at a similar level, suddenly finishes the year meaningfully in the black. The difference wasn’t talent or ambition – it was structure.

And Belderok’s perspective reminds us that races are under pressure too, with budgets ballooning even when prize purses stay fixed. “Money coming in means also a lot of money going out,” he says. That’s not an excuse. It’s a constraint.